# 3 | The Dangerous Ambition Behind CBDCs

The Triangle Offense Is Dead, Long Live the Triangle Offense!

This is another issue of Dirt Roads. No financial reports analysis, no marketing material dress downs, no investment advice, just deep reflections on the important stuff happening at the back end of banking. Because banking is nothing but a pragmatic translation of our ability to imagine what hasn’t yet happened, but could. The time you dedicate to read, think, and share, is precious to me, I won’t make abuse of it.

The Triangle Offence

Basketball’s triangle offence won Phil Jackson eleven NBA championships. At its core it was freelancing developed around a few fundamental tactical principles, and for this reason succeeded in combining adaptability, order, and the right degree of freedom for outrageous talents like MJ, Pippen, Kobe, Dennis Rodman, and my all-time favourite Shaq. The triangle offence had few simple principles. Principle one: you can draw an imaginary triangle with a centre, a weak side, and a strong side. Number two: ball movement should always have a purpose. Three: you are always on the offence. Four: you can’t make a mistake in the offence if you either hit the open man or cut the open area. Five: if you have a direct line to the basket, break the offence and go for it.

The most successful examples of adoption of the triangle offence playing system include the Chicago Bulls (1989-1998), the Los Angeles Lakers (1999-2004 and 2005-2011), and the modern monetary system (1971-?).

A (Very) Brief History of the Monetary Triangle

The triangle was adopted at Bretton Woods in 1971. Powerful at the centre was Government, designing systems and allocating spending. On the strong side, Central Bank, mandated to control monetary policy - and later regulation. On the weak side, Commercial Bank, dealing with clients and managing the infrastructure. It was a fruitful, mutually dependent, relationship:

Central Bank prints banknotes and uses them for several things, but mainly to (independently) purchase debt issued by Government

Commercial Bank selects creditworthy customers and lends them money, crediting their accounts and therefore de facto creating additional money in the system (within regulatory limits)

Commercial Bank parks some of those deposits into mandatory reserves with Central Bank

If those creditworthy customers desire to withdraw money from their accounts, Commercial Bank links to Central Bank and receives banknotes - this step rarely happens, as most money in the system remains virtual

This system has been working for a long time. It guarantees easy access to credit for both governments and private customers, a good distribution of tasks, and a sound system of checks and balances for an expansionary and innovating monetary system. It also inspires trust in the system by most actors; trust to lend, trust to deposit, trust to transact.

The Last Dance

However, just because the economy game is played in slow-mo it doesn’t mean things in the game haven’t been changing. I save you the plethora of charts, but over the last fifty years (in jumps), yields in Government debt have gone down, monetary base kept expanding, and the reach of Commercial Bank increased. The ball kept moving. The vertices of the triangle stayed the same, but relative power continued to shift. It went first from Government to Commercial Bank (and within the bank from shareholders to insiders but that’s a different story), then following the Great Financial Crisis from Commercial Bank to Central Bank (with yields on sovereign debt plunging to or below zero Central Bank became the buyer of last resort for state paper - in 2020 the FED owned 22% of total US debt stock, that number was 25% in the Eurozone and 43% in Japan). During the same period, although insiders were still having a reasonably good time, investors’ interest and returns in Commercial Bank plunged. In a parallel movement, counteracting market forces, regulation has tried to rebalance powers while guaranteeing the stability of the system and, going back to our basketball analogy, keeping the team in check.

Things continuously evolve. Demands on retail payments have been changing with a shift away from cash towards digital payments (exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis), technology companies entered the space providing a better user experience for peer-to-peer and B2C money transfers, alternative lenders started to design products targeted to very specific needs, blockchain technology provided for the first time a credible alternative to activities traditionally the monopoly of banks (e.g. market making, exchanging, book building, and even deposit creation).

Then, on the 23rd of June 2021, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS - the sort of union of central banks) pre-released a chapter of their Annual Economic Report dedicated to Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). A day that will remain in the (geeky) history books of monetary policy.

CBDCs, in the BIS definition, can offer in “[…] digital form the unique advantages of central bank money: settlement finality, liquidity and integrity. They are an advanced representation of money for the digital economy.”

Interestingly the authors, somehow defensively, at the very beginning of the paper state the reasons central banks should get involved in the digital currency space:

“Central bank interest in CBDCs comes at a critical time. Several recent developments have placed a number of potential innovations involving digital currencies high on the agenda. The first of these is the growing attention received by Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies; the second is the debate on stablecoins; and the third is the entry of large technology firms (big techs) into payment services and financial services more generally.”

Let me translate this for you from bureaucratic jargon. The BIS is angry. The report continues:

Very hard on BTC. “By now, it is clear that cryptocurrencies are speculative assets rather than money, and in many cases are used to facilitate money laundering, ransomware attacks and other financial crimes. Bitcoin in particular has few redeeming public interest attributes when also considering its wasteful energy footprint.”

A bit more gently on stablecoins. “Stablecoins attempt to import credibility by being backed by real currencies. As such, these are only as good as the governance behind the promise of the backing. They also have the potential to fragment the liquidity of the monetary system and detract from the role of money as a coordination device.”

Cautiously on tech. “Perhaps the most significant recent development has been the entry of big techs into financial services. Their business model rests on the direct interactions of users, as well as the data that are an essential by-product of these interactions. As big techs make inroads into financial services, the user data in their existing businesses in e-commerce, messaging, social media or search give them a competitive edge through strong network effects.”

The BIS sets its case very clearly and very early. Summarising:

It is worried about the unregulated investment area of crypto-tokens - but this seems an isolated problem that could be dealt with in a simple regulatory manner to reduce AML risk and protect (retail) customers (à la MiFID)

It doesn’t like the birth of stablecoins as digital and decentralised representations of fiat currencies - fearing the disintermediation of the monetary transmission mechanism

It is truly afraid by the fact that huge tech firms are entering the space - with all their bargaining power, access to private data, and closed ecosystems, tech companies could bypass the traditional open monetary system at some point in the future, in ways the BIS (nor any other) cannot think of yet

The motives behind BIS intention to innovate seem in other words defensive rather than proactive. Whether the BIS acts in order to protect public good or its own position of power is not an intelligent topic of discussion; what matters is that central banks believe in good faith in the importance of their position at the centre of the economy and are ready to act in order to defend it. I tend to agree with them.

Give Me the Ball

What are CBDCs, or rather retail CBDCs?

In oversimplifying terms, retail CBDCs would allow customers (private and business) to deposit money directly in central banking accounts. This would dramatically reduce credit and counterparty risk; differently from banknotes, our commercial banks deposits bear some level of risk above what guaranteed by deposit insurance schemes (if the bank goes under it’s not straightforward you can get all your money back).

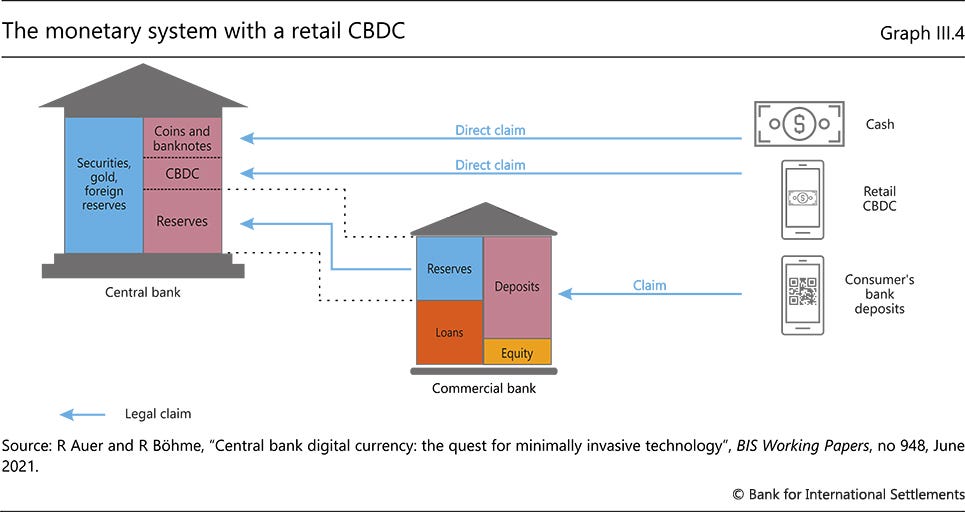

This is not little thing, and the authors are aware of the huge implications that CBDCs would have on the traditional banking system. Commercial banks, as we described above, have done a lot of dirty and less dirty work in the money creation game; now their centrality in the post-CBDCs monetary system isn’t guaranteed. The chart below (from the paper) outlines the issue very clearly.

From the report again:

“Although CBDCs and FPS [ed. Fast Payment Systems] have many characteristics in common, one difference is that CBDCs extend the unique features and benefits of today’s digital central bank money directly to the general public. In a CBDC, a payment only involves transferring a direct claim on the central bank from one end user to another. Funds do not pass over the balance sheet of an intermediary, and transactions are settled directly in central bank money, on the central bank’s balance sheet and in real time.”

If we ignore all technical and technological implications (national and international payment rails, privacy and data management, technology to create and manage CBDCs, etc.) there are few very big questions remaining:

Question 1: if you can deposit your money at the headquarter of money (Central Bank), why would you hand it to Commercial Bank instead?

Question 2: if you don’t deposit (the same amount of) money with Commercial Bank, how would Commercial Bank have the liquidity to lend?

Question 3: if Commercial Bank doesn’t lend money anymore (or less of it), who is going to lend money to customers?

Question 4: if Commercial Bank will be less active in the business of lending, what would Commercial Bank do?

I am sorry about the continuous quoting from the report but it is truly so telling:

“Indeed, there are good arguments against a one-tier system fully operated by the central bank, ie a direct CBDC (Graph III.7, top panel). Direct CBDCs would imply a large shift of operational tasks (and costs) associated with user-facing activities from the private sector to the central bank. These include account opening, account maintenance and enforcement of AML/CFT rules, as well as day-to-day customer service. Such a shift would detract from the role of the central bank as a relatively lean and focused public institution at the helm of economic policy.”

“Most fundamentally, a payment system in which the central bank has a large footprint would imply that it could quickly find itself assuming a financial intermediation function that private sector intermediaries are better suited to perform. If central banks were to take on too great a share of bank liabilities, they might find themselves taking over bank assets too.”

A one-tier system seems unpractical, so the BIS finds inspiration from China for a two-tier hybrid banking system (still with a much more active role of Central Bank):

“This “hybrid” CBDC architecture (Graph III.7, centre panel [ed. below]) allows the central bank to act as a backstop to the payment system. Should a PSP fail, the central bank has the necessary information – the balances of the PSP’s clients – allowing it to substitute for the PSP and guarantee a working payment system. The e-CNY, the CBDC issued by the People’s Bank of China and currently in a trial phase, exemplifies such a hybrid design.”

The impact is indeed so big.

From there on, the report tries to calm the waters and describes ways the impact of CBDCs could be limited in order not to disintegrate (literally) the financial intermediation mechanism as we know it. The result, however, is patchy at best. The emergence of alternative financial intermediaries during the recent past (in payments, specialised lending, investment management, product placement, etc.) had more to do with the inability of traditional banking players to offer customers the quality of experience they demanded (or at excessive costs) than with anything else. The introduction of retail CBDCs would push the pendulum further in this direction and it is difficult that putting technical limitations to their impact would work.

When compared with emerging financial intermediaries, banks remain the most trustful when it comes to dealing with, and depositing, our own money. If CBDCs would offer savers an even better and less risky solution, what would be the surviving competitive advantage of Commercial Bank? And if banks retrench, albeit progressively, who would take their place?

On the other hand, the benefits of CBDCs for the public would come at a cost, lack of privacy and loss of control for one, pushing part of the public towards ancillary assets that live outside of the full control of central banks. A digital asset enthusiast (i.e. a crypto bro) would argue that, since CBDCs would force more holders into the digital currency space, other digital assets would be the ones to truly benefit. I am not in a position to comment.

Alea Iacta Est

CBDCs adoption timeline is still uncertain, but with the BIS report the intention has been clearly stated. Power has recently been shifting away from traditional commercial banks, putting central banks and governments in a dangerous close loop, separated from the rest of the economy. The money triangle as we know it is starting to show signs of age. The creation of CBDCs is a possible answer to the ongoing power shifting and a plausible revamp of the monetary triangle. Whether the edges will remain the same is a different story. Of the three players traditionally involved (Government, Central Bank, Commercial Bank), it is Commercial Bank that appears the one at risk to be traded out. Every dynasty has an ending.

A civil war for money is on. Unfortunately, civil wars tend to be the cruelest of wars.