# 37 | Capital Structures for Stablecoin Protocols: the Revenge of the Sith

MakerDAO Is Gearing Up for One of the Largest Fund Raising Efforts in DeFi History

When I finished university and applied for my first job in management consulting, as every other ambitious yet spineless fresh graduate, I picked the only company focusing exclusively on financial services clients. Banks, in 2006, were cool. Banks, also, were typically located in the nicest and most central neighbourhoods of Western European capitals, and back in the day I wanted to travel. Nobody had told me that the package would have come wrapped to another, slithering, implied assumption, i.e. that I would have been for ever married to one of the largest, and most specialised, industries on the planet. Demand is always high for banking specialists. The economy is growing? Banks get creative and demand capital. The economy is shrinking? Banks need to restructure and need capital. You can say I tried to get out of the vortex and that it was just too difficult. I guess it’s the same for any relationship of codependency.

The public always confuses bankers for those who understand banking. Reasonable, but mistaken. Bankers tend to team up in industry (and product) teams, and a telecom banker knows much more of the telecom business (and of its financial needs) than of banking matters. Those bankers who dedicate their career to serve other banks, the bankers’ (or FIG - as in Financial Institutions Group) bankers, are a very specific breed. And everybody despises them. They are the losers among losers. Every investment banker dreams of a way out during his endless spreadsheet-ing nights, of the greener pastures of private equity or of the startup world. But not FIG bankers. Their life is hopeless. Condemned to golden servitude, they belong to an industry warped onto itself, ignored by the rest of society. Although deeply philosophical and fascinating, banking for banks has remained for most mysterious and ultimately uninteresting. This, at least, until DeFi made lending and borrowing relevant to literally everyone, unleashing a plethora of fintech marketing gurus to comment on things they haven’t the slightest clue about. And so hardcore banking-for-banks was resurrected, who would have guessed. If you are coming into DeFi from fintech with a bag full of the brightest ideas on how to rewire the financial system, just know that probably someone locked in a dark office of Canary Wharf or Wall Street or Basel, someone you never heard of, has thought about it a couple of decades ago.

I too have been a miserable bankers’ banker. And this is my revenge.

Understanding Financial Institutions

If you think you understand how a bank works, think again. You don’t. It’s counterintuitive. And the more experience you have in anything that has to do with finance, and corporate finance specifically, the more difficult it is. That is because the world of a financial services company is upside-down. The meaning of basic concepts such as assets, liabilities, equity, simply doesn’t match. The way you project those companies is different, the way you value those companies is different, the way you manage their balance sheet is different. If you have been CFO at Unilever for 20 years, you’d better not venture inside the offices of J.P. Morgan. Unless you are a client of course. FIG bankers, or the bankers’ bankers, are the quintessential representation of everything people don’t understand nor appreciate of investment banking. But they know what they are talking about. And they are basically alone.

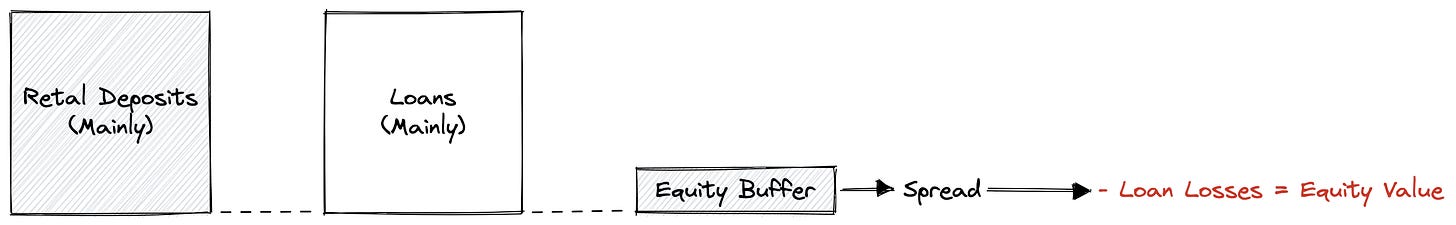

In a traditional company the entrepreneur finances his projects via a combination of debt (cheaper is preferable) and equity funding. His ambition is to minimise the cost of the required financing (liabilities) in order to build those assets that ultimately will generate the company’s cash flows.

Banks are different. Banks collect the cheapest and stickiest sources of liquidity in the market and deploy that liquidity for the highest risk-adjusted yield. In doing so, they have the ability to make money by managing both assets and liabilities. When you have access to ultra-cheap liquidity such as, for example, retail deposits, you really shouldn’t need the backing of annoying equity investors. The reality, however, is different, and the deep uncertainty that banks are exposed to generates volatility, and in order to digest that volatility those banks need a buffer. The bank’s equity capital is that buffer.

Sizing a bank’s equity buffer doesn’t come without tension. Being a buffer to protect against (unknown) unknowns, more equity funding doesn’t mean necessarily more financial resources to lend out and therefore more returns. This means that equity holders want to minimise that buffer - assuming a constant expected profit more equity means a lower Return on Equity (RoE) for investors. Nobody wants to keep idle money burning in a pocket. Depositors, on the other hand, are parking liquidity in a bank account for convenience rather than profit making, and want to be protected against the volatility of the loan book. For this reason depositors would prefer the largest equity buffer possible. In the middle, criticised and abused by many, is the regulator. Being the bank’s lender of last resort and the guarantor of retail depositors - within a well-defined limit, the regulator sets a bank’s minimum capital requirements.

Slicing the Cake

It’s not so easy. Banks need to remain viable businesses and in a market economy investors need to be incentivised to provide the equity backing required by the regulators. That’s why banks and regulators got creative in the definition and categorisation of what constitutes capital for a bank.

The best place to start our journey to understand what constitutes capital and how banks are managing their resources is the Talmud of banking, a bank’s Pillar III Disclosure Report. Here is Santander’s. The bank, one of the leading financial institutions in Europe, needs to comply with several pieces of regulation for what concerns its capital base: the most updated Capital Requirements Regulation - CRR, the Capital Requirements Directive - CRD, the local transpositions by the Banco de España, several EU-level rules, and its own internal corporate policies. To make it even more complex, these bits of regulation are in continuous evolution - we are now in CRR II and CRD V land, and getting ready for CRR III and CRD VI. A lot is covered by the regulatory body (what the reasonably acquainted public knows as Basel rules) but we will need to remain on the surface for the benefit of this article.

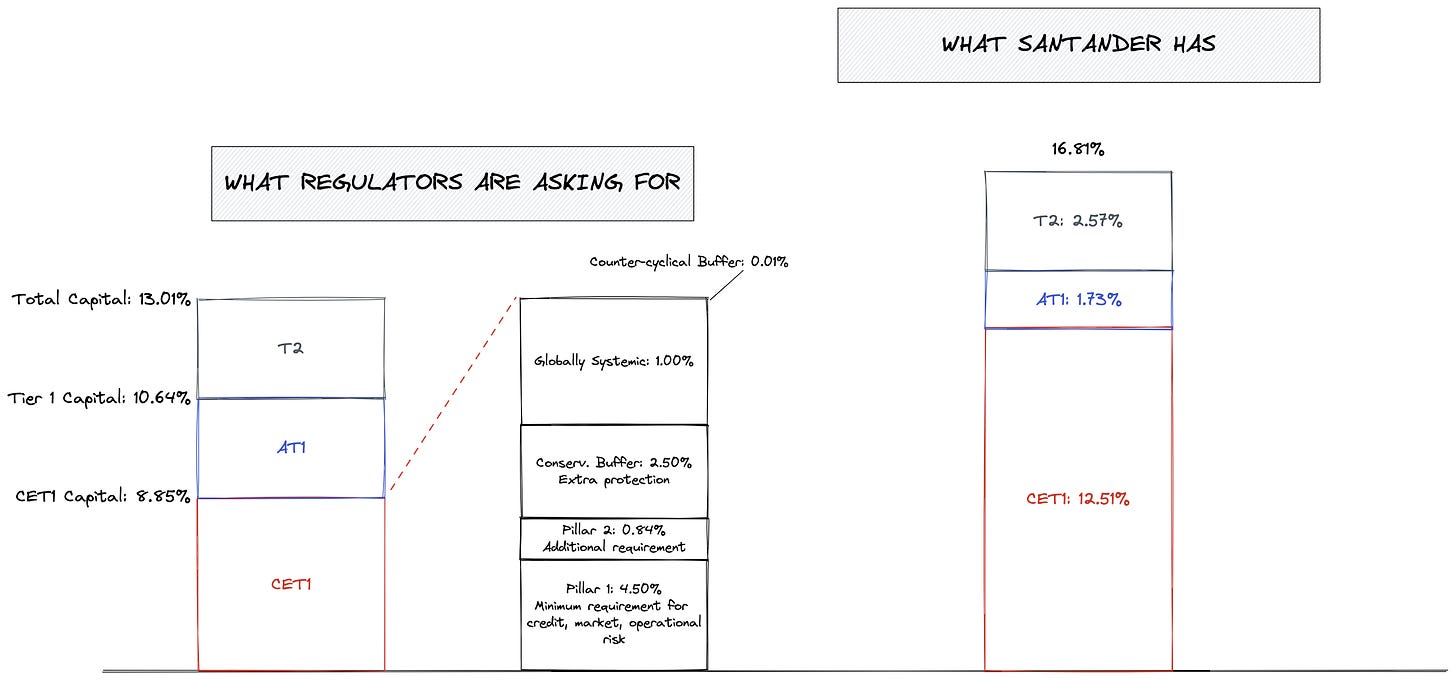

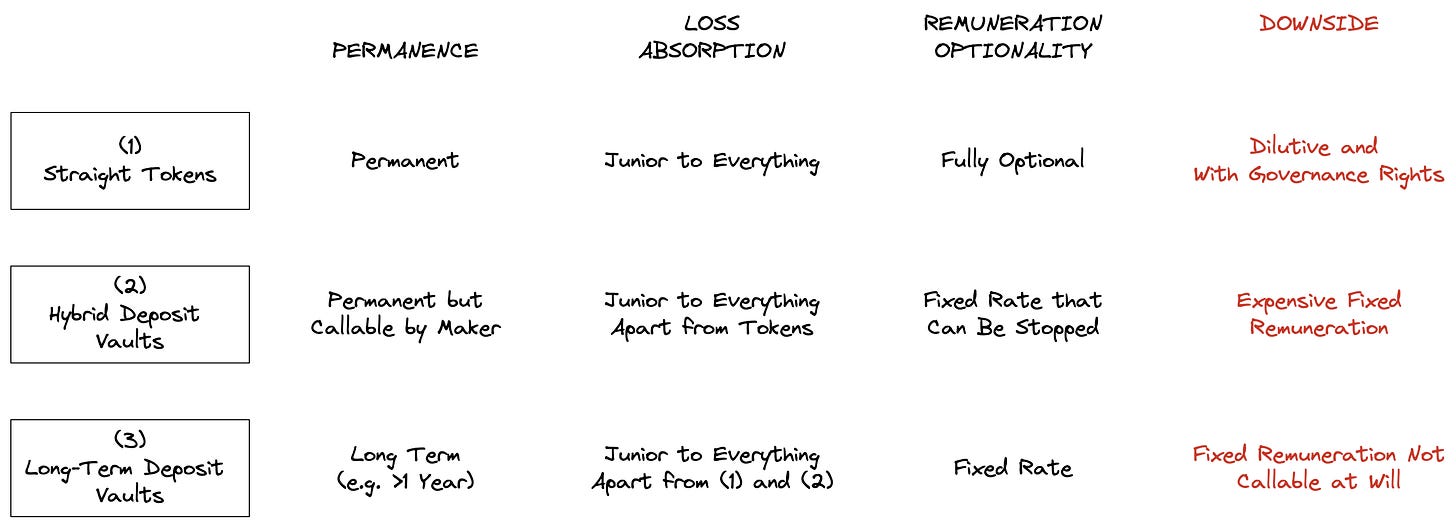

What are Santander’s capital requirements? Banks get creative to minimise the cost of the capital raised to satisfy regulators, and therefore regulators need to be prescriptive about what among existing financial instruments truly constitutes regulatory capital. Regulators slice capital in layers, qualifying each layer based on its (i) permanence, (ii) ability to absorb losses, and (iii) remuneration optionality. From the highest to the lowest quality capital:

Common Equity Tier 1 - CET1: perpetual, junior to everything, fully optional when it comes to remuneration (that comes in the form of dividends)

Additional Tier 1 - AT1: potentially perpetual, junior to almost everything, carrying contractual yet optional remuneration (default isn’t triggered if a bank doesn’t pay the preferred coupon)

Tier 2 - T2: long term, junior to most other liabilities, with contractual remuneration (it is split into Higher and Lower T2)

In the chart below are Santader’s 2021 capital requirements. For the uninitiated, Santander is required by the regulator to retain at least 13.01% (of risk-weighted assets) in total capital, with at least 8.85% in common equity. If they don’t have enough, and they don’t generate enough profits to replenish it on time, they have to raise it in the open market with a rights issue - which is dilutive and costs a lot of fees to be underwritten and distributed by investment banks. If they don’t comply options are a bail-in - where every debt holders loses a bit to achieve what’s needed, a bail-out - where the government steps in and puts the required money, and a loss of the license to operate. How does the regulator arrive to that very specific 8.85% number? By adding a lot of more granular requirements that are linked to Santander’s specific position as a globally systemic bank. No need to go into the details.

Below, we can see on the right hand side that the bank’s current capital position is significantly above the requirements at 16.81%. Why would a bank keep more than required in capital, if that’s diluting RoE? Because banks are in the trust business, and more capital means more trust, and more trust means a better rating, lower cost of funding, more opportunities to do business, and space to innovate and explore more profitable business lines.

The report goes on describing the many other requirements - Leverage Ratio, Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity requirement, Net Stability Funding Ratio, Minimum Requirement for Own Funds and Eligibility Liabilities, etc. Ultimately it goes into the detail of how capital is calculated, and how the bank manages its resources. A bank’s Pillar III is a thick document, and it’s no fun.

Ok, But Wen Crypto

Why does all this matter for us? We don’t care about traditional banking, we are re-wiring the financial system through smart contracts, right? Sure, but it would be helpful to avoid repeating the mistakes of history and build on the shoulders of someone else.

No matter how you look at it, lending and borrowing require some level of trust and extrapolation. Even in the world of trustless smart contracts, even in crypto’s over-collateralised lending model, profitable lending comes with the assumption that the underlying collateral will still be worth something (and that it will be liquid enough) in case of disposal. The holders and users of stablecoins should always remain comfortable that there is enough value (hard or soft) backing the currency.

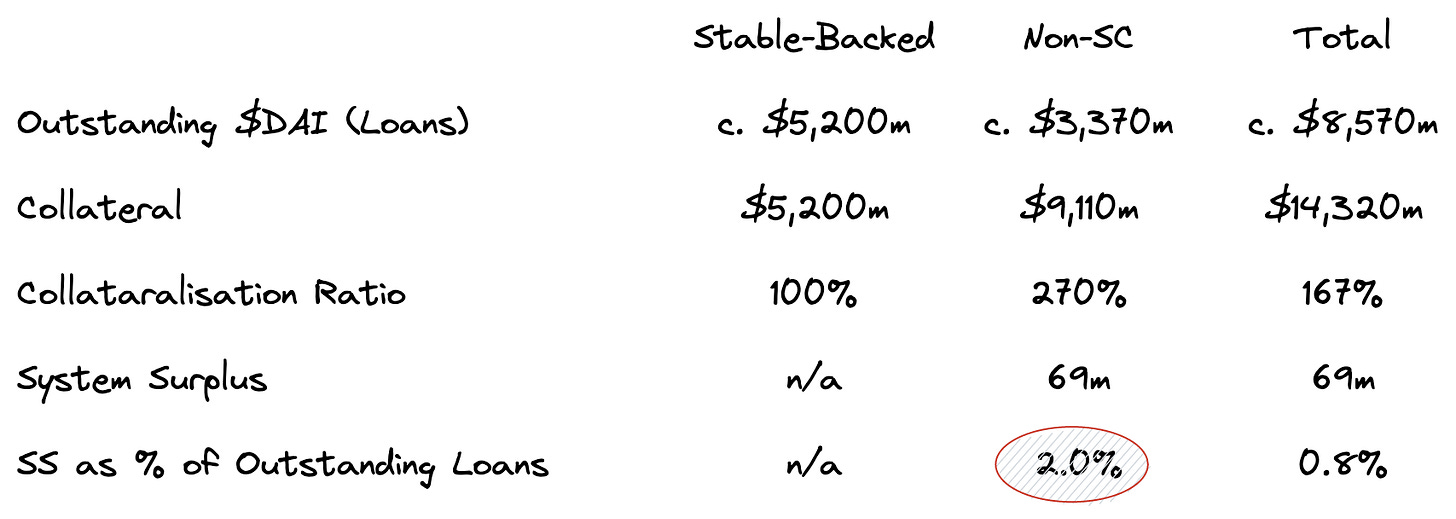

In the case of MakerDAO the best comp to a bank CET1 capital is the System Surplus - or SS. Maker’s SS currently sits at c. $69m. If we exclude risk-free loans (the fact that $USDC is risk-free is a big assumption) the SS as a % of risky loans is 2.0% - well below the 8-12% of a traditional financial institution.

The very prudent over-collateralisation of all loans (up to 270% if we exclude stablecoins) is only a partial answer to the thin capitalisation problem. As we have learned from traditional banking, credit risk is only part of the picture. It is true that in the case of Santander credit risk represents 87% of total capital requirements, but Santander is a large company, with a huge cost structure that is dedicated also to mitigate significantly operational risk, and not relying entirely on permissionless (experimental) technology.

MakerDAO is a protocol and not a people-heavy corporate, and it is plausible that generic business and execution risks are higher than Santander’s - especially if we consider smart contract risk. Maker, in addition, relies on markets remaining deep enough to execute collateral auctions when they are needed, liquidity risk (i.e. the risk of collateral auctions not going as planned due to persistent lack of market liquidity) is real for the protocol, and should be accounted for. When judged in the context of those existential risks, the SS’ $69m are a negligible amount.

On the 16th of March @hexonaut and other Maker community members published a forum post that highlighted the under-capitalisation issue. I was among the authors. Speed is everything in an environment as fast paced as crypto - you can read here about the ongoing philosophical war between Maker and Terra for the control of the stablecoin space. Without a sizeable contingency buffer it would be unwise for Maker to explore new, and less stringently safe, growth avenues such as institutional vaults - that with higher concentration have higher liquidity risk for collateral auctions, real-world assets - that are opaque and necessarily relying on centralised intermediaries, and multi-chain expansion plans - think about bridges and shiver.

The conclusion is simple: to be able to grow while remaining loyal to its currency protection mandate Maker will have to increase the SS by a factor of 5x or more, or by $200-300m.

Maker’s $300m Fund Raising Plans

A fund raising plan follows indicatively few phases: (i) estimate the capital gap, (ii) identify potential sources of capital, (iii) test investors’ appetite, (iv) execute.

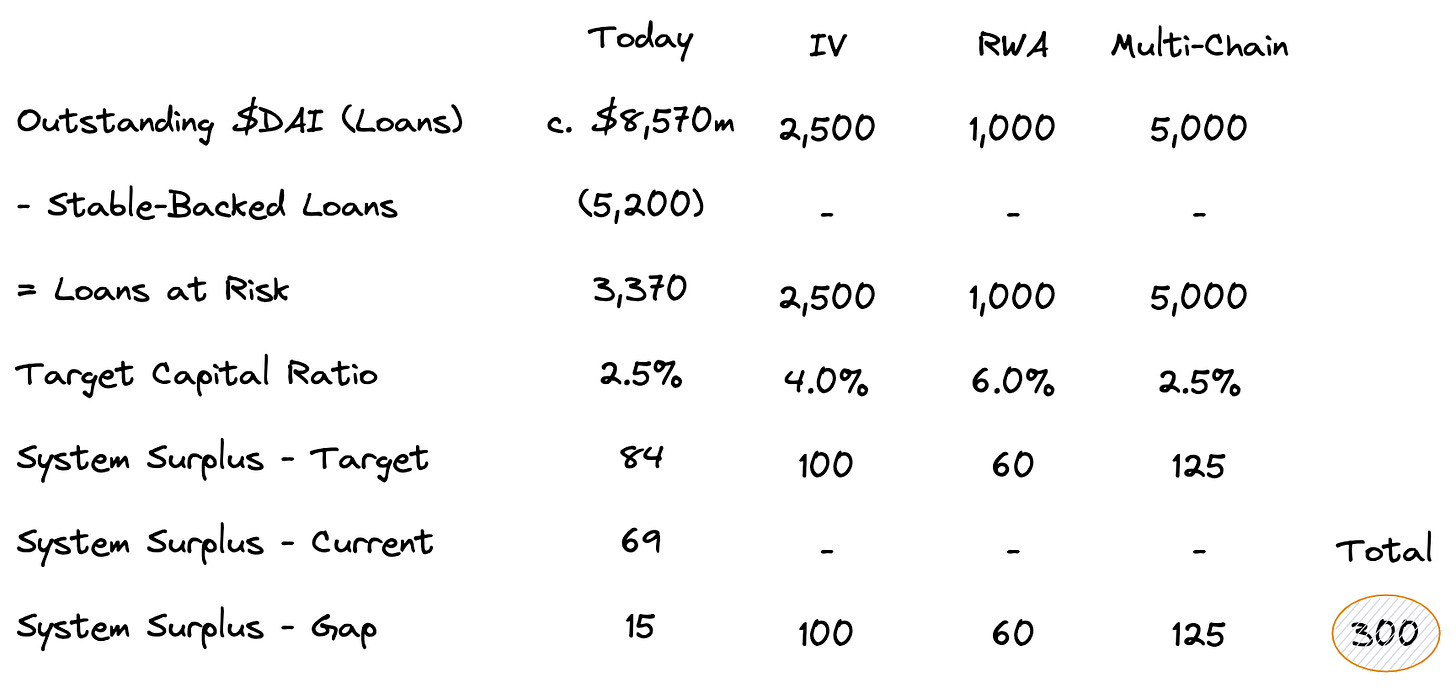

(i) Estimate the capital gap → In order to estimate Maker’s current capital gap, the teams should reach a measure of current exposure, and define a target capital ratio. With little historical data, it is more art than science. Let’s assume, for the sake of this example, that Maker settles on 2.5% total capital vs. existing risky loans. That would give us a current capital gap of $15m. Following this, the team should try to identify the capital requirements of each initiative. In our example, institutional vaults (IV) could attract more capital because of concentration risk - e.g. 4%, real-world assets even more due to opacity of the structure and reliance on external counterparties - e.g. 6%, and multi-chain expansion something similar to existing business - e.g. 2.5%. The sum of all those capital gaps gives us our required additional System Surplus. Obviously the protocol keeps generating profits in the meanwhile, but for simplicity we can assume that those profits will go to satisfy the expansion of all the other business lines and pay for the workforce. The result is the table below - again treat these as dummy numbers.

(ii) Identify potential sources of capital → Step two is figuring out what’s the best way to raise the identified capital gap. That’s where the fun is. We can learn from traditional institutions. As we have said before, capital sources can be ranked based on (i) permanence, (ii) ability to absorb losses, and (iii) remuneration optionality. Yes, straight equity/ token capital is by far the best source of capital we can aim for, but also the most expensive, and often it is unnecessary to fill the gap solely through a straight token issuance. Tokens are heavily dilutive, and in the case of DAOs they come with complex governance implications. Are there other options? For sure there are. Below are a few high-level ideas I would like to discuss with the DeFi community.

Straight tokens are easy. Once issued, they are permanent - unless bought and burned via auctions. They are great in absorbing losses being junior to everything else, and their remuneration is fully optional. The downside is that they are extremely dilutive, and that they would have significant governance implications that are difficult to predict. Straight tokens issuances should be handled with care, even when they are done at the best possible time.

Hybrid deposit vaults are fun. Here is where we could get creative. Imagine a vault where $DAI owners deposit their currency for a fixed remuneration in perpetuity. Those deposits are junior to almost everything (apart from tokens) and cannot be redeemed unless the protocol calls them. What calling means can be discussed - but simplistically we could think that the protocol has the ability to stop the perpetual stream and repay the accrued $DAI to the LP token holders. Those deposits would act in all shape or form like a token but with a fixed (or parametrical) remuneration that could be as high as 10%. Yes, they are expensive for the protocol, but also redeemable. A hybrid deposit vault could be set and depositors could act in a permissionless way to deposit their $DAI. If you are feeling Anchor Protocol vibes you are not mistaken, we could consider those instruments as an evolution of the eye-catching yield model pioneered by Anchor.

Long-term deposit vaults are flexible. The other, remaining option, are longer-term deposit vault. Those vaults would have a fixed duration (or set of durations - e.g. 3-6-12-18 months) and pay a fixed rate. LP tokens cannot be callable at will by the protocol, but can still be bought and burned in the open market. The fixed remuneration would be lower than hybrid deposit vaults, but would still constitute a cost for the protocol. Those vaults would be the most senior lien in the capital buffer.

(iii) Test investors’ appetite → The crypto VC and market-making capital market is deep. Large venture funds have been raised and credit funds are now showing up. It is fair to assume there would be interest in the market to provide financing to one of the oldest, most profitable, most central, and most stable protocols in DeFi. Institutional capital is actively seeking longer-term lending solutions at predictable rates - look at Maple’s success in the space of uncollateralised lending or at the attempt to create a rates market by protocols like Notional, Element, or IPOR. I firmly believe that both perpetual and fixed-term permissionless vaults would be well received by the market. There are other exciting implications. Fixed term institutional vaults (in size) could help bootstrap the secondary market for rates, where participants trade actively around different durations or rates expectations. In addition, a strip market for voting rights could be spun off, with perpetual vaults trading against straight $MKR tokens - that carry voting rights. As usual, the implications are endless and I should calm my enthusiasm.

(iv) Execute → The last and most important phase will be smart contract execution. Ultimately, the market will decide capital quantum and composition, but communication will go a long way. The initiative just makes sense. Growth is a priority for MakerDAO and other protocols, but growth shouldn’t come at the expense of sustainability, especially when the protocol manages something as central as currency.

$DAI holders should always be able to sleep well at night.

Thank you for bringing to light an idea that has utility in the DeFi space!

I traded hybrid bank products for a living for many years and now that I am getting into cryptocurrency and learning as much as I can about DeFi, I can see a lot of potential in fixed income and hybrid products in this ecosystem. It's good to see others are interested too.

Late comment to his post, but just wanted to say this was a really cool idea, especially the debt vaults - would love to see this pave the way for more protocols borrowing against future revenue streams.

One quick note: Do you think deposit insurance might cause a fundamental issue with the comparison between capital structures in this post? As you've pointed out, all deposits at most of these banks are backed by the government, so governments get to dictate the amount of risk banks can take. However, IMO these risk numbers (even though they got a lot better post financial crisis stress-testing) don't really reflect a "market pricing" of risk taken on by banks when giving out credit; mostly just numbers that governments have decided reflect safety.

"For this reason depositors would prefer the largest equity buffer possible" -> the crux of my point is that this is actually very relevant in DeFi (especially post Terra) but pretty much irrelevant to retail bank depositors because of government deposit insurance. In my view, banks just prioritize the interests of equity-holders as much as permitted under current regulations (depositors care about things other than risk in my experience) -> If Maker is able to execute on this plan, it would be really interesting to see the kind of "buffer" that the market wants, and how Maker actually balances the interests of depositors and tokenholders. I'd predict that eventually, depositors might expect a higher buffer than is given by current retail banks (assuming the same level of risk on the lending side).