# 39 | On the Long-Term Sustainability of Economic Systems

What We Must Learn from Terra’s Demise

Let me clear the air. I was right about Terra but it doesn’t make me feel any good.

Enough has been written in the aftermath of Terra’s monetary debacle. About the successful concerted attack to its currency — $UST, the sustainability of its sovereign (Anchor) yield, the centralisation of decision making and reserve management, the future of the algorithmic stablecoin construct as a whole, the impact on regulation and on the future of the industry. In my opinion, however, most of what has been discussed over the last week is not adding any value to what could have been outlined before. Terra’s surge and collapse happened exactly how most independent researchers had anticipated: slowly, slowly, slowly, and then suddenly. But things could have ended up in a completely different way — with LFG succeeding in their attempt to rotate Terra’s balance sheet by swapping tens of billions of $LUNA into $BTC and other exogenous assets. A longer bull market, lower inflation data, the avoidance of few tactical mistakes, could have made an epic bankruptcy into a success.

For each of us, however, it is always a matter of risk and return, as we have discussed already on Dirt Roads here — in late 2021, here — when activists started getting involved, or here — following the announcement of Curve’s 4pool. I have been a $LUNA investor and (mainly) a $UST depositor for a while, but with open eyes and a finger ready to double-tap and get out in case of signs of distress. And rest assured that those signs started coming in. I titled DR’s 34th release “Anchor Protocol (II): Too Big to Thrive” and chose Akira’s dark nuclear explosion as cover image. A few weeks later, release #36 dubbed the confrontation between Terra and Maker as a “War of the Worlds”, underlying the philosophical distance between an on-chain over-collateralised model and a naked algorithmic one. It was never a matter of being right or wrong, or of good and evil, or of belief and disbelief, but one of relative value and risk management.

As many of my fellow crypto economists and investors know, I decided to liquidate all my Terra exposure on the second week of April, right when the quality of the debate was tanking at least as fast as Anchor’s currency reserves. I was a small fish so exit liquidity wasn’t a concern. That decision saved me a significant amount of money, but more than anything acted as a reminder to trust my own research when what’s happening outside doesn’t really make logical sense.

It doesn’t, however, make me feel any better.

The Middle Way

Economic systems exist to attract agents who possess certain resources (e.g. time/ labour, ideas/ productivity improvements, past time/ capital) and interact to achieve a specific goal. This definition is a framework that can be widely applicable to pretty much anything from families to corporations, countries, and beyond.

All those agents have different endowments and time horizons. Labour providers, for example, often have the immediate need to look after their survival. Capital providers, on the other extreme of the spectrum, are ready to temporarily part from accumulated wealth in order to achieve future gains. Economic systems can work well because they act as the clearing house for all those different needs, matching them in the forward-moving struggle towards a common desire.

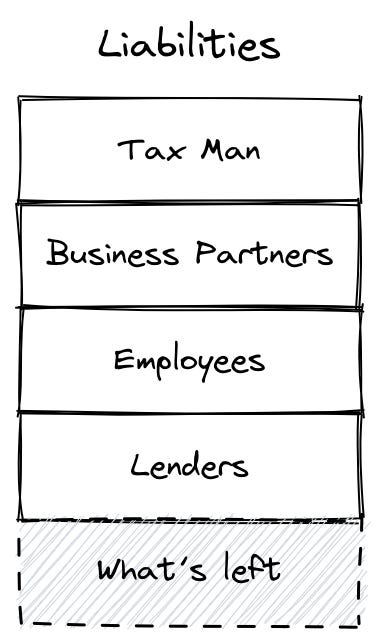

The corporation → When looking at the corporative economic system, it is easy to figure out who’s providing what by looking at the liability side of the balance sheet. Equity investors, lenders, commercial counterparties, employees, tax authorities, they all have a claim on the (present and future) value controlled by the business. They have, however, very different sets of preferences:

Tax authorities: democracies are distributed tyrannies, and the state has coercive power over anyone who operates within its sphere of influence — for this reason it shouldn’t come as as surprise that the state typically asks to be paid back first

Commercial counterparties: those players are ok to swallow time mismatches in order to keep doing business, but certainty of payout is of paramount importance for a frictionless functioning of the supply chains — this is why commercial debt tends to be structured as the most senior claim on a company’s assets (following tax-related liabilities)

Employees: depending on the jurisdiction, and the political inclination of the government, employees enjoy widely different levels of protection

Lenders: those extending financial debt tend to be larger and risk-averse institution (for many reasons — including their own high leverage like in the case of banks), and for these reasons they require fixed payouts and a senior claim attached to specific assets (secured) or to the company as a whole. Unsecured debt, for clarity, doesn’t mean absence of guarantees, but rather that guarantees are more generically provided by the future cash flows of the company

Equity investors: after everyone else gets paid, the providers of equity capital come to ask for what’s left — they are the most junior in the capital stack but in exchange have the ability to exercise control on the direction of the business and can make a disproportionated return on their money

A solid, sustainable, corporation, keeps the interest of all its liability holders balanced with each other. When this doesn’t happen it’s usually sign of trouble. During the years that preceded the Great Financial Crisis, for example, the senior management of some of the largest financial institutions was using its influence to capture a disproportionate slice of the generated economic value — this created distortions in the way business was conducted that in the long term blew everything up at the expense of all other liability holders: banks’ equity investors saw their share of ownership diluted by continued rights offerings, lenders suffered severe haircuts, many employees were made redundant without having participated to the feast, and the state had to spend tens of billions of taxpayer’s money in order to avoid contagion.

The country → The same reasoning can be applied to government finances. As an Italian, I am innately familiar with the issue. The Italian treasury is one of the most indebted entities in the world — with net debt over GDP sitting at c. 180%.

Japan is somewhat similar — with other traditionally more market oriented systems quickly catching up. Both Italy and Japan heavily invested on their infrastructural and welfare layers during a period of solid growth, and those layers couldn’t be so easily disbanded when growth started slowing down. It is not a coincidence that both countries are among the oldest in the world, enjoy the longest life expectancy, and have pension systems that are built on national guarantees. Italy, in addition, has suffered for decades from sclerotic productivity in the public administration and unhealthy levels of corruption in the private sphere. If caveated enough, the same can be said of Japan.

What most people ignore, however, is that Italian households are among the least indebted in the world. You can extrapolate what’s going on: one interest group (private — typically older — citizens) is exercising influence on national politics in order to transfer a disproportionate slice of national wealth to themselves through off-market pension schemes, lenient tax authorities, and suboptimal investments on innovation. They are not stupid, they just care for themselves and have a different set of preferences when compared to the rest of society. Democracy isn’t always guarantee of the best possible outcome.

Imbalances, however, cannot last for ever and Italy itself (as well as Greece — also on the chart) has consistently shown fragility when accessing the international debt markets in moments of stress, notwithstanding the fact that its industrial sector is still the second largest in Europe — after Germany. The secret, again, seems to be in the ability to balance a diverse set of interests.

The good news is that the status quo of each economic system can be easily analysed: sometimes it is good enough to look at a snapshot of who’s amassing the most value within a system to understand what’s going on and, more importantly, to predict what might (most probably) happen in the future.

The same argument could be applied to Terra.

Terra: a Sovereign, On-Chain, Monetary System

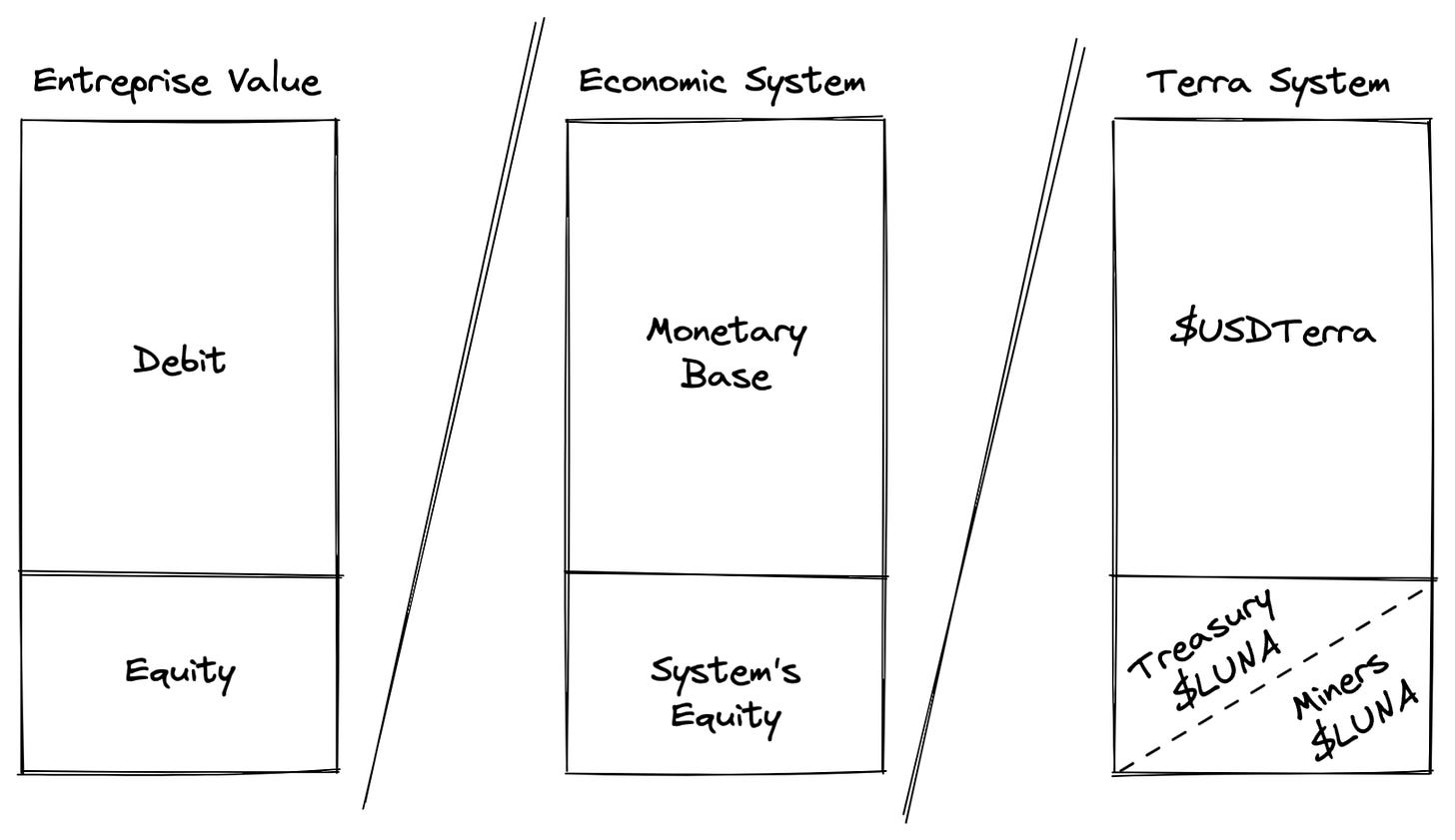

Terra is, or better was, a sovereign monetary system, with its own currency, $UST, implicitly pegged to that of the biggest economy it interacts with, and its own governance token, $LUNA. Said in computer engineering jargon, the Terra Protocol run on a Proof of Stake (PoS) blockchain, where miners staked its native token $LUNA to mine $UST transactions. $LUNA represented the mining power of the network.

$UST and $LUNA were symbiotically connected. When inflows slowed down and the $UST suffered of de-pegging pressures, the system tried to counteract by issuing more mining power (trying to incentivise further external actors to interact with Terra) and using the proceeds to buy-and-burn $UST. When inflows instead accelerated and the $UST could become more expensive in USD terms, the system tried to counterbalance the effects by minting more currency and using that currency to buy-and-burn mining power, i.e. $LUNA.

Terra kept shifting volatility between $UST (its system’s liability) and $LUNA — its system’s equity. One was a reservoir for the other, and both were existential. $LUNA holders benefited from token appreciation during periods of large influx of liquidity, and couldn’t afford an aggressive outflow of $UST due to a reduction in Anchor’s deposit yields. The Terra ecosystem needed Anchor. Desperately. In early April 2022 $LUNA’s circulating capitalisation reached $40b, more than 10x its value one year prior. Rather than due to the increase in mining revenues, the appreciation was directly correlated to the outstanding growth of the monetary base, with $UST reaching 18b of circulation. Said differently, Terra’s implied systemic leverage grew exponentially over the previous year, placing it in the impossible situation of having to stabilise the interest rate demanded by its lenders — Anchor’s depositors.

4pool → On the 1st of April @ezaan posted on Terra’s forum about the Community’s intentions to partner with Frax and [REDACTED] Cartel in order to boost $UST’s multi-chain usage. He made clear it wasn't April Fools’. How did they want to do it? Through a newly-deployed Curve pool named 4pool, composed of $UST, $FRAX, $USDC, and $USDT. Exactly, no $DAI. The deployment would be tested on Fantom and Arbitrum chains first, and then finally activated on mainnet. They argued it was about liquidity, but I insisted it was about the cost of liabilities, mainly. By successfully replacing $DAI’s 1.5b 3pool volume Terra would save c. 300m / year of passive interest, more than enough to justify bribing costs, but not enough to solely compensate the depletion in Anchor reserves. I was missing the other side of the picture: augmented liquidity would have provided the necessary window to swap in the open market exogenous assets (like $BTC, $ETH, $AVAX, $SOL, etc.) in exchange for $LUNA.

The forces that had pushed $LUNA along its incredible growth trajectory (namely leverage) were slowing down due to structural limitations (you can’t increase leverage for ever) and instead started being counteracted by selling pressure now that the core team started to think about using native assets to purchase exogenous ones. Everyone has a different set of preferences. As a team member bootstrapping a crypto economy from nothingness the name of the game was saving the boat, even at the cost of a reduced valuation. As an investor, however, deciding whether to deploy fresh financial resources into the system, $LUNA wasn’t a rational place to be. More could be said of $UST depositors: with a reduction in the support provided by the valuation of $LUNA, the turmoil due to a natural slow-down of capital inflows, and the clear preference of the core team to focus on the preservation of their own equity, the 20% yield was definitely not enough.

I decided to get out.

Again, balance, again, lessons from the past, again, the clear risks of centralised control and extreme skin in the game. It happened. By opening the liquidity floodgates in order to churn Terra’s balance sheet the team simultaneously exposed the system to those able to create turbulence and benefit from it. The rest is history. Market participants started flooding decentralised and centralised liquidity venues to force a break in $UST’s peg, Terra’s team was forced to sacrifice (part or all) its exogenous reserves to protect it — causing a collapse in market liquidity and valuations, $LUNA was attacked as the ultimate reservoir of stabilisation, trust rapidly evaporated, and the whole system went down.

But it could have happened in many other ways. Discussing those events is like discussing football tactics: entertaining, unnerving, and unnecessary. What matters most is debating the system’s structure and trying to anticipate the events based on what is in front of our eyes at any point in time: growing leverage, centralisation of control, abrasiveness in all communications, and a growing attraction for dogma and religious zealotry. With great power comes great responsibility, nobody is ready for it and nobody should have it. The secret, probably not attractive enough for the movies and the sensationalist tweets, continues to reside in prudence, repetition, and balance.

Stay safe out there. And be kind.

This was useless asf. Began great, ended terribly, never delivered on promises.