# 8 | Primitive Obsession: I Swear I Just Wanted To Write a Review of Compound Finance

Chasing the Elementary Constituents of DeFi Lending Protocols

This is another issue of Dirt Roads. Those are not recaps of the most recent news, nor investment advice, just deep reflections on the important stuff happening at the back end of banking. Because banking is nothing but a pragmatic translation of our ability to imagine what hasn’t yet happened, but could. The time you dedicate to read, think, and share, is precious to me, I won’t make abuse of it.

Truth Is a Function of Time

In 1962, Thomas Khun published The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. The book was for the philosophy of science what Gödel’s incompleteness theorems were for the philosophy of mathematics. Khun challenged the hypothesis of monotonic linearity in the evolution of science by introducing an episodic model where periods of continuity were shaken by the discovery of inexplicable anomalies, and ultimately abrupt paradigmatic shifts. In a process of never-ending creative destruction, a paradigm is pushed to the limits of its explanatory powers to then be burned down when it becomes unusable. From Aristotle to Einstein and beyond, each paradigm had a taste of ultimate truth and made the predecessors look stupid. Khun affirmed that this paradigmatic evolution is, on the one hand, unavoidable, meaning that it is meant to happen and will continue to happen, and, on the other, incommensurable, meaning that the new paradigm cannot be proven based on the tools of the old. In simpler terms, the new is destined to become the old, and the old and the new cannot communicate and agree on anything. Every truth is just a function of time. Including this one.

Unfortunately, we are the product of the paradigm we live in. It is unavoidable that in trying to frame and describe what is in front of us we continuously refer to what happened to us before. As individual agents, we have structured and compartmentalised the information received in order to make some sense of the world and now new information needs to fit in the preexisting structure. The older you get, the less space there is.

Compound Finance: Combine Finance

The same happened to me when I sat to write a long overdue deep dive in Compound Finance for Dirt Roads.

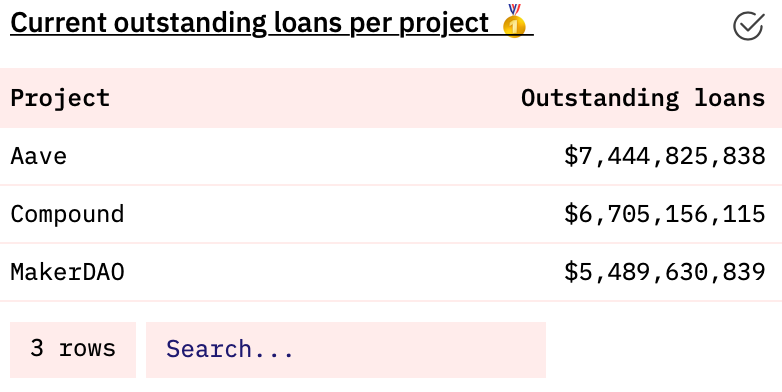

Launched in 2019, Compound is today part of the Holy Trinity of DeFi lending, together with Aave and MakerDAO. Bundling the three together, however, tells a lot about the unhelpful simplifications that happen in the world of DeFi. All three are considered lending protocols, but while the core functionality of MakerDAO is that of expanding the crypto monetary base (exactly like a bank) via minting new stablecoins backed by asset tokens, that of Compound is matching the different maturities of asset tokens to satisfy a variety of use cases. They both refer to their callable functions as borrow and lend, but the actions behind do not have much in common.

Using old fashioned names to promote new solutions is indeed a great marketing tool, but that shouldn’t satisfy any serious financial analyst, being from TradFi or DeFi. With the introduction of its proprietary chain and, especially, its real world bridge for corporate and banking treasuries, Compound has been the most successful in marketing its usability - for borrowers. But what is exactly Compound? A deep dive in the evolution of the protocol is an introductory course on the clash of opposing forces that happens within every corporation, or any social aggregate in general.

Compound is a protocol on the Ethereum blockchain that establishes money markets, which are pools of assets with algorithmically derived interest rates, based on the supply and demand for the asset. Suppliers (and borrowers) of an asset interact directly with the protocol, earning (and paying) a floating interest rate, without having to negotiate terms such as maturity, interest rate, or collateral with a peer or counterparty.

The above is the definition given by Leshner and Hayes in their 2019 white paper. There is no reference to lending in it.

In order to avoid falling into the trap of fitting new stuff into old shapes, we need to first go back into the world of traditional banking.

TradFi: the Old Way of Doing Things

From the outside, banks are monolithic institutions. Truth, however, is that behind a single line in any financial statement there are several, completely different and often competing, activities. Although Pillar 3 reporting helped in giving outside investors a better perspective of what happens inside an institution, the reality is that it is impossible, from the outside, to sufficiently grasp what goes on within the corporate domain. We call it politics. That is why most financial cataclysms seem obvious only in hindsight.

From Credit Suisse’s report on Archegos Capital, following a USD 5.5b loss booked by the bank (as usual, emphasis is mine).

On February 19, 2021, the PSR analyst sent a dynamic margining proposal to the Head of PSR for internal review, noting that he had made the terms “about as tight” as possible, yielding an average margin of 16.74% if applied to Archegos’s existing swaps portfolio and leading to a day-one step up of approximately $1.27 billion in additional margin. This was less than half of the additional initial margin that would have been required if Archegos’s Prime Brokerage dynamic margining rules were applied to Archegos’s swaps portfolio. On February 23, 2021, the PSR analyst covering Archegos reached out to Archegos’s Accounting Manager and asked to speak about dynamic margining. Archegos’s Accounting Manager said he would not have time that day, but could speak the next day. The following day, he again put off the discussion, but agreed to review the proposed framework, which PSR sent over that day. Archegos did not respond to the proposal and, a week-and-a-half later, on March 4, 2021, the PSR analyst followed up to ask whether Archegos “had any thoughts on the proposal.” His contact at Archegos said he “hadn’t had a chance to take a look yet,” but was hoping to look “today or tomorrow.”

Politics hurts.

During my strategy consulting years the name of the game was the alignment of incentives. The best financial institutions were focused on decomposing risk through a combination of internal transfer pricing policies, while structuring compensation schemes pushing agents to act in the interest of the whole bank. Realising that net interest income is a combination of several value streams, banks started to develop transfer pricing for everything, from liquidity (i.e. making liquidity users pay to treasury for what they were locking) to credit (i.e. stripping the cost of credit risk out of front office profits and creating a P&L for risk managers), and SG&A. Others, even more sophisticated (typically corporate or institutional banks) developed a bidding system based on the Economic Value Added (EVA) of each large transaction, where the various teams bid the EVA they were ready to bring in if the deal would have been approved - that bid would then become the team’s budget. Those were the years of the Great Financial Crisis and everybody had the same ambition: to find an equilibrium among the plethora of agents and go back to satisfactory profitability without inflating new destructive bubbles.

The Imperfect Totalitarianism of Corporate Policies

Banks were, and still are, trying to do three things:

Identify and separate the key activities impacting their business

Allocate sufficient resources to each of those activities

Align the incentives of those resources to minimise perverse actions for the organisation

A set of corporate policies is developed to achieve those goals. If you really want to understand what are the primitives upon which the complex architecture of a bank is based, you needed to study the corporate policy books. There are two main problems, however: the first one is that only insiders have access to (most) corporate policies, and the second is that it is very difficult to simulate the interactions among those policies and, consequently, identify the potential flaws that could generate monsters at some point in the future. In the example above, even if Credit Suisse had (maybe) the right high-level policies in place to control counterparty risk in their prime brokerage business, incentives were not aligned to push all the agents to act effectively on those policies. With organisations getting more and more complex, and businesses less and less transparent, the visibility and control issues are massively amplified.

That is why, from the outside, analysts got complacent and kept using simplistic primitives when describing banking activity: lending, borrowing, risk management, liquidity, solvency, etc. If, for example, we would instead look at lending from a more granular perspective, we would identify several sub-activities: origination, risk(s) underwriting, price settlement, ongoing monitoring, credit collection, customer relationship management, etc. Each activity has competing ambitions, each activity should be regulated by a policy, and each policy should be implemented through an incentive system for those involved, hoping to achieve a good equilibrium.

It is simply impossible to be so granular, while remaining effective, in traditional finance. That is why, in my years as private equity owner of financial institutions, my main job was visiting companies and make sure everybody was talking to each other as they should have.

DeFi protocols are translating into executable, compilable, and testable code what old school corporate governance used to write in paper policies. This should, in parallel, enhance our ambitions of how we look at the value chain. Treating Compound as a lending protocol is as good as treating Geneva’s CERN accelerator as a machine to study the universe: it works to describe it to the general public, but it is completely useless among physicists.

Paradoxically instead, DeFi protocols are making this refinement process less urgent by squashing almost every source of risk onto token volatility, or market risk. If we exclude protocol security and governance, also called endogenous risks - and that would require a separate discussion, every source of bad surprises for a protocol user is embedded in the pricing dynamics of the asset tokens in use. And there are many different things impacting the pricing dynamics of asset tokens.

Compound 1st Primitive: Automated Term Structure

That was a long introduction, but what does Compound actually do?

Algorithmic rate setting. In the Compound protocol, token holders contribute their ERC-20 assets to a liquidity pool in exchange for a floating yield, dynamically calculated. On the other side borrowers contribute collateral assets and in exchange can temporarily obtain other assets by paying a floating cost, dynamically calculated. The protocol applies the concept of bonding curves, introduced by Hansen in the context of Automated Market Makers, to deterministically define a spread between active and passive interest rate for each market, i.e. each asset. At each point in time (block t), those constructed rates (or term structures) are a function of the market’s utilisation rate plus a set of parameters to incentivise participants and guarantee a sufficient spread as a cushion for the protocol.

A well functioning algorithmic rate setting would be one that attracts sufficient users, while maintaining positive net assets. Compound has been successful in doing both.

In an era with very little yield competition, the introduction of Compound Treasury has been another (heavily subsidised) way to bring traditional dollars onto the protocol. With the offer of a 4.00% APR and the promise of liquidity it is not difficult to understand why. Although we are sure regulators won’t stay at the window and watch, the marketing intention is clear: Compound is trying to capitalise on its early mover advantage.

Who is going to get the benefit of growing volumes is not clear yet though. As of today, holders of COMP (the protocol’s governance token) have only governance rights and there is no other way they capture value from the platform’s usage. This doesn’t necessarily mean that there won’t be value streams for COMP in the future, or that the COMP token has no value. Valuation, however, is not the focus of this post.

Compound 2nd Primitive: Automated Liquidation Engine

The Comptroller is the risk management layer of the Compound protocol. Comptroller defines the level of collateral needed to borrow tokens and all the liquidation parameters involved in case the collateralised position becomes excessively risky. It is the way Compound protects the liquidity providers in case of exogenous shocks, incentivising those providers to participate.

Liquidation mechanism. The process of liquidation of excessively risky vaults, automated within the Compound protocol, acts in protection of the liquidity providers via incentivising liquidators to buy out collateral. In their fantastic study, Qin, Zhou, et al. highlight that most lending protocols work very well in incentivising liquidators to close positions; actually excessively well, and at the expense of the borrowers. The attractiveness of the liquidators business is confirmed by the severe gas price competition among liquidators and short bid intervals in auction liquidations.

The liquidation mechanism of Compound (and Aave - so-called fixed spread) grants the liquidator the right to liquidate a percentage of collateral that exceeds what would be needed de minimis to bring back the position in good health. This design decision further favours liquidators over borrowers. Liquidators are, in return, exposed to the risk of loss due to price fluctuations of the collateral during the liquidation, but the use of flash loans in fixed spread liquidations (like that of Compound) drastically reduces this risk.

Flash loan. The atomicity of blockchain transactions (executions in a transaction collectively succeed or fail) enables flash loans. A flash loan represents a loan that is taken and repaid within a single transaction. A borrower is allowed to borrow up to all the available assets from a flash loan pool and execute arbitrary logic with the capital within a transaction. If the loan plus the required interests are not repaid, the whole transaction is reverted without incurring any state change on the underlying blockchain (i.e., the flash loan never happened). Flash loans are shown to be widely used in liquidations.

The workflow goes as follows:

Liquidator borrows a flash loan in currency X to repay the debt

Liquidator repays the borrower’s debt with a flash loan and receives collateral in currency Y at a premium

Liquidator exchanges parts of the purchased collateral in exchange for currency X

To close the flash loan, the liquidator repays the flash loan together with its interests, the remaining profit lies with the liquidator; most importantly, if the liquidation is not profitable the flash loan would not succeed

The real winners are, in other words, liquidators, i.e. something quite close to TradFi market makers, at the expenses of the borrowers. This sounds quite familiar: read Robinhood. As for Robinhood, the fact doesn’t seem to bother borrowers too much. This might have something to do with good users acquisition strategy, marketing, and the main use case of borrowers: trading on the margin. The optimistic mindset of levered (non-institutional) traders can obfuscate the mind at times.

Compounding Early Competitive Advantages

We have taken the long route to describe what Compound is actually doing in the DeFi ecosystem, but it is difficult to judge how good something is if we do not understand first what exactly that thing is trying to do.

We have opened up Compound’s wrapper and identified two protocol primitives: (1) automated term structure, and (2) automated liquidation engine. The protocol bundles those two primitives together (they do not necessarily belong together) in a user experience that was at inception, and probably still is, superior to that of most competitors. The extension of the product line and creation of integration bridges (with other blockchains and other DApps) is working towards further improving this experience, further attracting users on the platform even if they are not the ones benefiting the most from its design.

But DeFi is modular, we know it by now. It means it can push the construction of any complex tool to smaller and smaller elementary blocks. That is why extraordinary returns are mostly achieved by betting early on solutions that will demonstrate themselves superior to what already exists, or on new primitives that could be combined in a superior solution yet to be built. That is also why it is difficult to retain the (token) value of the same solutions over the long term. But that is a different governance and incentivisation issue that would be better solved outside the protocol itself. Ah, the combinatorial power of modularity is truly mind bending.

Compound strategy, however, might not be a mistaken one. Competition among DeFi protocols is hot, and defending early competitive advantages is extremely difficult in a purely modular and commoditised space. What Compound is trying to do is improve customer loyalty by providing a good experience and attractive UI. Although it has a strong TradFi aftertaste for me, in the non-institutional world it might just be enough.

Innovating is a process. It starts with sourcing ideas, and proceeds with disseminating those ideas for testing, funding and high-quality execution. For this reason, it is collegial in nature. If you have great ideas you want to share, great companies that should be on Dirt Roads radar, or topics you would like to co-author on DR, please feel free to reply to this email or contact me on Twitter.

Is it possible that Tarun's paper had a mistake which you copied here in your image for interest rates? From looking at the compound whitepaper and this blog (https://ian.pw/posts/2020-12-20-understanding-compound-protocols-interest-rates), it seems like the borrow rate is just (beta_0 + beta_1*U)... and it is the supply/lending rate that is U*(beta_0 + beta_1*U), forgetting about protocol reserve fees here. Could you please confirm that this is correct, otherwise I'm really confused.