# 46 | The Great Convergence: $GHO and the Story of the Five Old Kings

Minting Currency Is Great and Everyone Wants a Piece of It

This week I lost a dear friend, and I truly didn't feel like writing. I debated, and ultimately decided that the best way to react to tragic events is by reflecting upon the gift of life, doubling down on what we love and showing respect for those who have suffered. This week, however, Dirt Roads might miss some of its rhetorical verve, I am sure you will excuse me for that.

The River, the Pond, and the Lake of Legends

Money stopped flowing through the gates and the ecosystem is changing. Those that perfected the catching net for the tumultuous rivers of 2020 might not be the ones that will master the placid lake, or better smelly pond, that is late 2022 DeFi.

DeFi liquidity, that almost reached $200b at the beginning of 2022, now lingers around $60b—source DefiLlama, and doesn’t show signs of improvement. While we wait for technological—the merge and the deployment of L2 scaling mainly, governance, and regulatory progress, the DeFi crowd is splitting in two: in one corner those focused on connecting new pockets of the world to the tech, and in the other the ones dedicated to morph and capture as much remaining liquidity as possible—while positioning themselves for the next bull run. Whatever will bring the bull back. Islands in the stream.

Recently, Dirt Roads has focused way more on the first bunch, and especially on TradiFi<>DeFi bridge builders and governance framework innovators. For good reasons: I care more about changing the world than stealing another piece of the pie. The degree of integration of blockchain-based finance with the outside world is all yet to be proven. Today, however, we shift to the second one: the liquidity catchers.

We can start by eyeballing the top 5 DeFi names by TVL—again DefiLlama. The list is a good representation of the ossified DeFi sector of our days, and gives a sense of the playing field. It includes a sovereign lender—MakerDAO, a liquid staking provider—Lido, a money market superapp—Aave, and two DEXs, although very different from each other.

In the pre-crypto reality, the financial sector has always been a derivative of the underlying economy, with a size that is a fraction of the net present value of the economy itself. Finance, ultimately, is an allocator and distributor of resources, and a financial sector folded onto itself is rarely a sustainable one. In aggregate, of course. Coherent with this framing, the current DeFi sector bases its value onto the intermediation of two economies: the Ethereum ecosystem—which could be compared to crypto’s sovereign industrial sector with measurable throughput, and the US economy. DeFi has pitched itself as a more efficient distribution layer for the allocation and transfer of resources, and it is entirely understandable that such layer has been massively dollarised over the years. People do indeed use DeFi to transfer and store their dollar wealth, and that’s a good thing. Web2 had a similar trend, with commercial and political capital flowing through the pipes of social media developed in the Silicon Valley. In my opinion, a self-referencing DeFi is an unhelpful illusion.

It is unclear what will be the next zero-to-one innovation that will help the industry making the jump towards the next phase of its evolution. In the meanwhile, while they wait for the next big inflow of liquidity, most OGs have started flexing to steal market share from others. A phase of great convergence has begun, starting around the most successful product to date: stablecoins.

The Currency Rush

But why are stablecoins, or more in general currencies, such an attractive product to develop? Let’s forget philosophy of money for a second and focus on the strictly financial characteristics of currencies. Currencies minted via a Collateralised Debt Position (or CDP) to be precise. Pragmatically, a borrower, who owns collateral, pledges such collateral to a counterparty, in exchange for a loan in stable currency form. The loan could be used for several purposes but that doesn’t interest us now. For the benefit of having the loan borrowers pay a Premium—in interests or fees, and give the ability to the lender to seize the collateral if it falls below a certain Liquidation Threshold. In financial engineering terms borrowing via a CDP is equivalent to packaging a structured financial product that involves some shorting and some option trading.

Phase 1: potential borrower owns the asset → At the onset, i.e. before taking on any loan, a potential borrower’s profits are linearly connected with the value of the collateral asset (e.g. $ETH) he owns; if value grows by $1 he will increase profits by $1.

Phase 2: borrower pledges his asset in exchange for a loan → By entering a loan contract, the borrower is de facto selling the asset to borrow another—we can ignore the value of the other asset here. By selling (shorting) the collateral asset he is netting out his straight long; trivially, his net payout is now indifferent to the price movement of the collateral asset.

Phase 3: borrower retains rights to access the asset → By pledging (and not selling) the borrower is retaining the right to swap back, at any given point in the future, the borrowed asset for the one pledged. He is, in other words, purchasing an American call option. If the asset value grows above the Pledged Value (i.e. strike price) his profit will grow linearly. The Premium paid by the borrower is equivalent to the option premium.

Phase 4: borrower gives the lender rights to seize the asset at discount → The borrower, actually, is giving the right to the lender to seize the asset at a discount if the value falls below the Liquidation Threshold. This means that the inflection point of the borrower’s profit curve is not the Pledged Value, but rather the Liquidation Threshold, that acts as a backstop. The size of the discount helps the lending protocol to manage its balance sheet—by incentivising auction keepers to buy the collateral and sell it for a profit, but this is something that doesn’t concern us.

The charts above are quite simplistic, as they ignore the fluctuations in value of the borrowed asset—e.g. $DAI, and the fact that such asset can be swapped for more $ETH therefore increasing the sensitivity/ derivative of the payoff to $ETH prices. Those simplifications do not bother us, given that we are trying to prove how attractive is currency minting rather than borrowing. The charts stimulate the following reactions:

Lender has an infinite amount of assets to lend—or calls to write: a stablecoin minter can mint as much stables as desired, assuming there is enough collateral to mint against. It can also do this for free, given that the all-in marginal cost of its liquidity is pretty much zero

Good option writing is profitable: investment banks make a lot of money by writing and market-making options, and this is because they clip option premia from buyers—in the context of stablecoin minters liquidation penalties act as an extra sweetener

Parameterisation is key: in order to run a profitable option writing business careful parameterisation (of Liquidation Threshold, Premium/ Fee, and Discount/ Penalty) becomes key

Volatility is what matters: the Black-Scholes framework teaches us that the price of an option derivative is positively correlated with the volatility of the underlying asset, and volatility matters when picking parameterisation

Volatility of the borrowed asset makes things very complicated: we have assumed until now that the borrowed asset (e.g. $DAI) is stable in value, introducing volatility considerations also on that front makes modelling strategies (and parameters) way more complicated—a highly volatile $DAI might attract a very different type of users compared to today’s

Aave and the $GHO Project

The list of the top 5 OGs (remaining) includes only one minter of currency: Maker.

If I were Maker, or a large $MKR whale, looking at the top 5 DeFi chart would give me vibes of terror. For one reason or another, all those protocols control a huge amount of financial value and there is nothing forbidding them from trying to mask some option selling in the form of a stablecoin and cross sell it to their users. It didn’t come as a surprise when protocol #3, Aave, opened the dances.

At the time of writing, Aave hosts c. $10b worth of assets provided across 7 networks— including Ethereum, Avalanche, Optimism, Fantom, Polygon, and Arbitrum. More than $6b out of the $10b have been provided on the Ethereum market, with c. $1.9b being borrowed and the rest sitting at the protocol level. $USDC is Aave’s largest market on Mainnet, with c. $1.5b supplied and c. $430m borrowed. Volumes are high and spreads are tight, with supplied capital clipping a variable 0.33% (nota bene way less than US treasuries with the 3-month at c. 2.9% today) and borrowed capital paying a variable 1.24%. There are structural reasons behind the bid-ask spread—we have debated it when introducing Morpho and its plan to port crypto money markets towards an order-book framework, as well as mundane ones like taxes and convenience.

Please meet $GHO → In early July, the Aave team introduced to the community $GHO, its native, dollar-pegged, stablecoin idea. As with others decentralised stables, the minting engine would accept crypto collateral (based on governance-approved collateralisation ratios) and provide to those wallets a certain amount of $GHO. The same amount of $GHO (subject to lack of protocol losses) would be burned following repayment or liquidation. All fees would accrue to the DAO treasury.

Permissioned permissionlessness → $GHO could be permissionlessly minted by Facilitators, which are protocols, entities, etc. authorised (read permissioned) to interact with the currency engine. Each Facilitator gets assigned a Bucket, which represents the maximum amount of currency that a Facilitator can mint. Each Facilitator can be theoretically completely different, with individual risk profiles, as well as liquidity and technical characteristics. Here on Dirt Roads we have advocated several time for the emergence of a lending sun of last resort that would provide super senior protocol-to-protocol liquidity across DeFi, we had just assumed that such a protocol would have been Maker, not Aave. As usual, our own emotions can blind us.

Interestingly, and somehow naturally, $GHO’s first proposed Facilitator is the Aave Protocol itself. Governance would assign the Aave Protocol its dedicated Bucket to bootstrap the $GHO currency. Based on what has been shared on forums, the Aave DAO will rule upon $GHO’s parameters—including interest rates and Bucket assigned to itself, and the risk parameterisation and execution of its own market. I personally dislike governance commingling, but I guess we should wait for more details around the implementation and watch.

The chart below, published on the Aave forum, included also real-world assets (i.e. RWA) as potential Facilitator. We have debated at length on the complexity of integrating opaque (and heavily regulated) dumb contracts with the blockchain, and we are looking forward to read more about the implementation strategy when the first Facilitator of this kind will come online. The same can be said of delta neutral positions and market makers.

GHOsting Aave

How would the Aave Protocol Facilitator work within the $GHO context? The integration goes hand-in-hand with the launch of Aave V3, and benefits from several of its features.

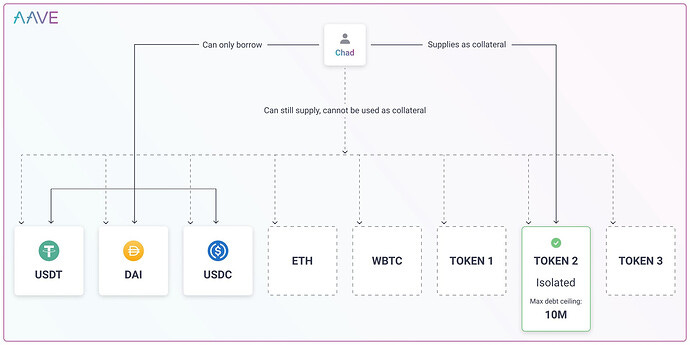

Isolation Mode → On V3, isolated markets can allow borrowers to post a specific asset as collateral, giving them the ability to borrow stablecoins from the protocol based on defined collateralisation parameters. The standard V3 approach aims at isolating (often novel) collateral volatility risk as a support for stablecoin suppliers, but it doesn’t change the core of the Aave protocol—the stablecoins lent out have been initially provided by other peers. With the integration of $GHO into V3, Aave becomes instead a conduit of freshly minted $GHO expanding Aave’s balance sheet in a way that, yet again, reminds a lot of the way Maker mints and distributes $DAI.

High Efficiency Mode (eMode) → eMode is another new feature brought forward by V3. Individual Aave markets can be categorised, based on certain selected features, and assigned a collateralisation factor and liquidity penalty. Categories, typically, wrap tokens of similar characteristics and highly correlated with each other—i.e. all stables, $ETH and derivatives, $BTC and derivatives, etc. Asset suppliers or borrowers, in theory, can benefit from commingling those currencies to diversify some of the idiosyncratic risks out, and ultimately get better rates and parameters. If you have perceived some Curve-y vibes you are not alone. By incorporating the ability to borrow $GHO against each category, Aave intends to internalise demand for both stable and volatile assets in bear and bull markets. Borrowers, the theory says, would borrow in $GHO against (e.g.) $ETH to extend their long position, or deposit stables to borrow more $GHO (with a close to one-for-one ratio) to bring their leverage down on the $ETH eMode when prices start dropping. V3’s Portal would allow liquidity to flow across markets and chains.

Flywheels and bootstraps → Aave protocol supporters would have preferential treatment in borrowing in $GHO by providing evidence of staked $AAVE tokens. The amount of $GHO funding available at discount (for each $stkAAVE provided) and the discount itself will have to be decided by governance. There are currently c. $280m staked in the protocol’s Safety Module, subject to a risk of slashing of 30% in order to protect the protocol against losses, against a c. 9% APR. Given the flimsy connection between protocol revenues and valuations, there is nothing bad in trying to use vibes to accrue financial value for governance tokens.

Risk of cannibalisation → There definitely is some risk of cannibalisation involved here, with demand of $GHO potentially causing utilisation and borrowing rates on deposited stables to go down further. However, it is fair to assume that the blended interest margin on $GHO is way larger than that retained on the money market side. My back-of-the-envelope calculations show that the margin retained by Aave on deposited $USDC is 1-2 bps only—i.e. 0.01-0.02%. We don’t know much yet about the launch of $GHO, and I guess the team is in no particular rush given the lack of borrowing demand in the crypto space nowadays, but the spread would probably be 50-100x larger than this.

The Next Dance

Aave might not be the most obvious candidate among the OGs for spinning its own stablecoin. Yes, it controls a lot of deposited value. Yes, it has the intention to become some sort of retail-oriented DeFi superapp and you need a stablecoin in your arsenal for that. Yes, the cannibalisation costs are moderate. Yet my top pick would have been another one: Lido. The runner-up? Curve.

Curve → And so it goes. At the end of July, Curve soft-announced they were joining the stablecoin war. Curve controls vast amounts of dollars in homogenous liquidity pools— $stETH+$ETH and $DAI+$USDC+$USDT are the largest ones. Currently, depositing into those pools spits out an LP token that has been used as the main weapon of the Curve bribing ecosystem. With the sustainability of the Curve Wars under scrutiny, the extra step that would see the use of such LP token as collateral for a native stable gets interesting. Curve would benefit from having already a deeply liquid market for potential liquidations. The downside? Most assets held in Curve are stablecoin assets, and providing funding backed by stablecoin collateral isn’t very profitable for the protocol as we have seen for Aave before and for Maker’s PSM—that makes zero revenues. True, the $stETH+$ETH pool is #2 with $1.2b TVL and that could be leveraged. There is another protocol, however, that controls even more Lido $ETH than Curve, and that protocol is…Lido.

Lido → There are c. $6.7b worth of $ETH staked at Lido in exchange for $stETH. The protocol hasn’t shown interest in developing their own native stablecoin yet, probably busy with other issues and the uncertainty around the looming Ethereum merge. That doesn’t mean, however, that it won’t happen. A successful transition to PoS, together with perfect fungibility of $ETH and $stETH, could provide the perfect terroir for Lido to develop a single-collateral stablecoin backed by $ETH staked natively on the platform. The UX experience could be smooth, with staking happening behind the scenes for borrowers. Monetisation could happen in the form of interest rates, or as a share of $ETH staking yield, making it almost seamless for the borrower. Liquidations could be run through various avenues, including Curve $stETH pool (that might continue to be incentivised by Lido via $LDO distribution) and other $ETH liquidity venues. My guess is that Lido might continue to incentivise liquidations through the existence of a large and deep market for $stETH—as it would help them keep value within the platform. If someone from Lido wants to bump ideas on the matter my Twitter DMs are open.

The great convergence has started, and it will most likely continue as long as the bear market stays with us. The competitive landscape of tomorrow might look way messier and more aggressive than what it is today, with a contracting effect on protocol margins and revenues. It is curious that no-one has embarked on a mission to attack the widest margin of the whole industry, that thick 3% US treasury spread captured by Circle when swapping dollars for crypto dollars. Somebody should wake up. I am making it a note to myself.