# 55 | The 10-Minute Guide to Tether Reserves

Balance Sheet Quality, Money Transmission, Shadow Banking, and the Law of Hard Numbers

Tether is good. Tether is bad. Tether is whatever you think it is. But numbers don’t lie. Look at the numbers, do the math, and decide for yourself. This is my very personal 10-minute guide to an informed answer on whether I’d reserve a significant amount of my own cash in Tether form—I said reserve not transact. The answer, maybe unsurprisingly, is no, although it is a nuanced one that depends on the numbers the company has shared with us, as well as on a set of assumptions I will detail below.

Tether: the Ring to Rule Them All

On the 10th of May 2023 Tether released their Q1 2023 report with the intent to make some noise. In the press release, two numbers hit the fantasy of all industry participants:

Group’s $1.48b (billions) of net quarterly profits

Group’s reserves at an ATH of $2.44b

Jointly with the press release arrived BDO’s audit reports on the quality of the Group’s reserves. As always, fame (and money) has the byproduct of attracting a lot of indiscreet eyes. What are those reserves (or assets technically) composed of? Is the $2.44b a good or bad number for the issuer of $USDT? Good vs. what? Below is my 10-minute (ok maybe 15-minute) take on Tether’s financial health and what this would entail for users and holders of $USDT. We will proceed in steps.

Assessing Tether’s Business Model

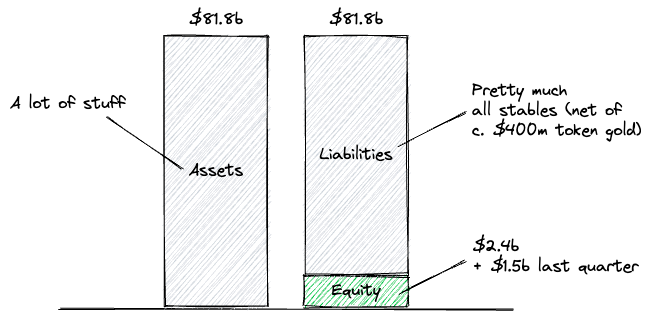

At the end of Q1 2023 Tether had issued c. $79.4b of digital tokens, mostly $-pegged stablecoins and a bit (c. $400m) of digital gold. Those coins give a 1-for-1 redemption claim to qualified holders. In order to back those claims, the Group held $81.8b of assets.

That’s more than 1-for-1 right? That’s great right? Not so fast. There are at least a couple of ways one could call Tether, and those business models have very different balance sheet risk profiles. As the minter of $USDT, the largest $-pegged stablecoin in circulation, Tether could be considered either money transmitter, or a bank.

Money transmitters → If Tether would consider itself a money transmitter, i.e. in simple terms a fintech that prints a digital version of the dollar that looks and smells and behaves exactly like the dollar, see Circle’s $USDC, its requirements in terms of permissible investments would be extremely strict and pretty much limited to (approved) bank deposits and (very) short-term US sovereign debt instruments. We have seen, during the SVB debacle—here, how those limits are far from being satisfactory in eliminating any type of risk stablecoin token holders are exposed to. Counterparty risk, in banking, it’s a real thing, but so far at least the central bank has stepped in when required. We should hope it keeps doing it, although we could do better than hope. The beauty of being a money transmitter is that you really don’t need to keep too much in reserves for rainy days, since guidance is constructed exactly to eliminate any possibility of a rainy day. Is Tether’s balance sheet compliant with the most common money transmission guidance around the world? The answer is obviously nfw, but you can see for yourself—there’s a bunch of stuff in that balance sheet.

Permissible investments under money transmission, based on my back-of-the-envelope calculations, are at best c. 80% of the total balance. Said differently, c. $15b of assets have a credit and market risk profile that makes the Group something else entirely.

Banks → Tether’s quarterly bottom line, the advertised $1.48b, should be another useful data point. In money transmission land we would expect profits to come mainly from fees and yield derived from risk-free investments. With rates at c. 4% and a balance of $81.8b, quarterly interest income should be c. $800m. Where are the remaining c. $700m coming from? Definitely not from fees, but rather from higher yielding credit assets (read non-US debt, corporate bonds, etc.) and the marking-to-market of directional investments—read commodities and Bitcoin. What is Tether then? In all shape or form, Tether is a very efficiently funded hedge fund—that pays 0% to its LPs, or technically an (unregulated) bank—given that it has a claim on issuing liabilities that should be considered at par with any other form of digital money.

The good news of Tether being a bank, at least for us analysts, is that we have pretty good benchmarks to assess whether the Group’s reserves are enough to keep us calm. Reserve capital, starting from the so-called Common Equity Tier 1 capital of Basel-land, is there because it is supposed to absorb the volatility of the asset balance—someone doesn’t pay you back, an investment you have done goes sour, interest rates swing, and the bank should be solid enough to absorb those oscillations. Regulatory capital buffering has grown to be almost punitive for banks during the years following the GFC, and paired with floored interest rates (and therefore anaemic interest margins) has made banking on average one of the worst investments from a return on equity perspective. Banks have had a big denominator—equity, not much numerator—profits, and a lot of unknown unknowns in their balance sheets. It is not surprising that most financial institutions trade at or below book value.

Assessing Tether’s Capital Position

In order to calculate the required equity balance to be kept aside by banks we should first translate assets into risk-weighted assets—or RWAs. RWAs are a like-for-like way of looking at assets, that takes into account the riskiness of each underlying category. Not all banks’ balance sheets are the same, and the regulator has provided mostly good guidance for standard comparisons. I say mostly, because certain captive exposures (namely sovereign credit exposure) have received over the years extremely beneficial weighting—but that’s actually good news for Tether.

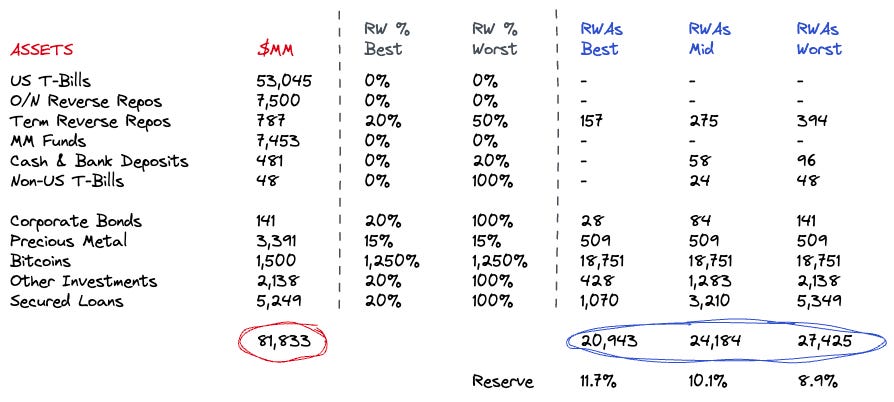

The BIS gives us good standard guidance to calculate RWAs that we can easily but non-scientifically apply to Tether’s balance sheet. Let’s go line-by-line.

US T-Bills: Tether’s keeps most of its assets in < 90-day maturity US T-Bills, that are quite favourably weighted at 0% by regulators—the rationale is that states don’t default (we will see about that) or that in general the risk profile of government bonds is kind of similar to that of the currency they print

O/N Reverse Repos: those are 1-day facilities fully backed by US T-Bills, and it makes sense to weight those at 0% as well

Term Reverse Repos: termed repos are covered by guarantors with A2 rating, or A in S&P—this type of counterparty would be weighted between 20% (if sovereign) and 50% (if corporate)

MM Funds: the nature of those is undisclosed, and we can benevolently assume their risk profile is similar to US T-Bills—hence 0% weighting

Cash & Bank Deposits: the treatment of banks deposits depends on the regulated nature of the depositary institution, going from 0% to 150%—we could cap weight at 20% in the worst case scenario

Non-US T-Bills: risk-weighting depends on the type of issuer, from 0% to 100% (BB+ to B-) or 150%—unrated issuers, we are assuming a range from 0% to 100%

Corporate Bonds: as for sovereigns, risk-weighting for corporate exposures ranges from 20% to 100-150%, we are using 20% as best case and 100% as worst case

Precious Metals: straight ownership of gold is not a loan, but has some directional exposure given that the price of the asset can fluctuate, the BIS has standard guidance for market risk as well—we are estimating 15% to be set aside in capital reserves to overcome underlying volatility

Bitcoins: similar to gold, exposure to $BTC has directional market risk, and has currently a punitive risk-weighting of 1,250%; although we could argue that this punitive weighting comes from the antagonistic position of the regulator towards digital securities, it is also true that $BTC is an extremely volatile asset and such a volatility should be appropriately reserved for

Other Investments: we don’t have a lot of details here, hence we are assuming a 20% best case weighting and 100% in the worst case scenario

Secured Loans: same as for Other Investments

The table below summarises my view on RWAs in the best-mid-worst scenarios. Net of a caveat on $BTC exposure we will describe later on.

How do Tether’s reserves look as a % of those RWAs? The estimated equity ($2.4b) ranges from 11.7% to 8.9%—or an average of 10.1% of RWAs. A couple of caveats. Caveat #1 is that only credit risk (apart from metals and $BTC) has been accounted for, and no additional reserving for other types of risks (interest rates risk, operational risk, etc.) has been included. Caveat #2, and this is a very important one, is the assumption that Tether doesn’t have any bad debt in its balance sheet—although it would be prudent to assume that Tether’s balance sheet includes non-performing exposures, assessing the required reserving for those would complicated things a lot. Taking the 10.1% number baseline is good enough for our analysis.

Conclusions on Tether’s Capital Health

How does the 10.1% number compare to an average (regulated) bank? At the end of Q3 2022, the latest aggregate data point I quickly found, European banks had an average 14.74% CET1 over RWAs. I didn’t take US as a benchmark given that every week there seems to be an American bank going under, but it wouldn’t be very different. Yes, that is more than Tether’s, translating into a capital gap ranging from $645m to $1.6b depending on our assumptions. Call it $1b. That’s a lot of money. Suddenly the ATH reserving doesn't seem so good anymore.

On $BTC → I know what some of you might argue against—the Bitcoin punitive risk weighting. With a more conservative risk-weighting for Tether’s $BTC exposure the required reserves would look very different. True, but it is that volatility that ultimately allows the Group to post astonishing profits (or losses) over the quarters. To be fair, if we had to take a more amicable approach over $BTC, and ask Tether to fully reserve their $BTC exposure, the risk-weighting would look more like 680% and not 1,250%. That would be the weight that (multiplied by a desired 14.74% capital ratio) translates into full reserving of the $BTC position. A 680% risk weighting would make Tether’s balance sheet more than satisfactory at the current $BTC prices and level of reserving—given the caveats we have stated above. The amended table is below.

Our analysis of Tether’s reserve quality, ultimately, is highly inconclusive:

Tether’s capital could be >$1.5b even ignoring other types of risk (e.g. liquidity and ALM) and assuming absence of non-performing exposures in its loan book

Those conclusions are highly dependent on Tether’s $BTC exposure—a more amicable treatment of $BTC from a capital perspective, as well as higher prices for $BTC, could help Tether covering the capital gap, as they have done during the last quarter

However, the elevated volatility of its balance sheet, coupled with the very limited transparency it gives to investors—Tether does not have a Pillar III report, do not seem to justify the 0% yield $USDT holders are receiving

Whether unregulated banking is better than regulated banking for money transmission is not for me to tell, although I have my opinion. One thing is clear though: there is a dark side to Tether’s so-good $1.48b quarterly profit headline.