# 62 | Ethena’s Odyssey: From Stable to Bond to Structured Product to Rollup

By the Time You Understand Ethena, Ethena Will Have Understood You

If I had to list the three most important books that influenced my view of crypto capital flows and my research methodology here on DR, none of them would be strictly about economics or business. If I really had to give a list (and I hate lists) the three winners would be Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent, and Wallace’s Infinite Jest. I’d probably throw in Gödel, Escher, Bach by Hofstadter too. What connects them? They’re interesting only to insiders, they are rhetorical as fuck, and they blend a weird mix of mathematical rigour and messianic visions of hyperreality. Plus, they’re excruciatingly long. Honestly, they’re also genius and have somehow reshaped our perception of reality from the ground up. Read them at your own peril.

The Two Faces of Ethena

Much has been written about Ethena, its $USDe, and the sustainability of a so-called stablecoin backed by fully digitally native assets. As someone deeply entrenched in the design space for cryptodollar products and committed to first-principle thinking, especially when it comes to sustainability, it was high time I delved into the matter. Sustainability, rather than profitability, aligns well with first-principle thinking, as it allows for a through-the-cycle understanding of design mechanics and market forces, making it easier to assess whether something is indeed sustainable, i.e. capable of continuing to exist for a long-enough time horizon. Determining what constitutes a long-enough horizon is a rather philosophical topic that remains outside the scope of this discussion.

A lot has happened in Ethena-land since the project was launched, but I believe it would be best to start from the very beginning: what is Ethena’s $USDe?

Ethena At Face Value: Delta, Yield, Solvency, and Peg

On its website, Ethena describes $USDe as a delta-neutral and yield-bearing instrument, sometimes referring to the instrument as a synthetic dollar and other times as an internet bond. Although along Ethena’s short life the nomenclature has definitely been important, before delving into nomenclature feuds it is essential to understand what the instrument is and how it works. This is the DR way.

$USDe’s main flows are the following:

Whitelisted users can mint $USDe by providing $stETH (and also $BTC but we will focus the analysis on $stETH here) and receive $USDe units on a 1-for-1 basis—minus gas and execution costs

The protocol simultaneously opens a corresponding short perpetual position on a centralised derivative exchange to achieve delta neutrality

The collateral backing remains visible on-chain but is custodied by off-exchange service providers—Copper and others

Whitelisted users can redeem $USDe for the underlying collateral (at a similar ratio) by following a similar inverse flow

Understand Ethena, $USDe, and its impact on DeFi requires covering the following aspects, which I think are the most important to dissect the protocol-enabled trade:

Delta neutrality

Yield profile

Solvency

Peg stability

(1) Delta neutrality → Derivative instruments, by definition, derive their value from that of another underlying asset. Consequently, the rate of change in the value of the underlying asset directly affects the rate of change in the value of the derivative itself. Delta (Δ) represents that relative rate of change. For example, with a Δ of +0.5, every +$1 increase in the value of the underlying asset results in a +$0.5 change in the value of the derivative instrument—or strategy. A delta-neutral instrument (or strategy) is one whose value movements are independent of the value movements of the underlying asset(s). In oversimplified terms, executing delta-neutral strategies requires using negatively correlated underlying assets or sub-strategies. Additionally, given that any trade implementation incurs some friction, a proper delta-neutral strategy can be executed if there is a sufficiently large and sustainable mismatch payoff between the two legs of the trade to cover transaction and other costs. Crypto, unfortunately, does not yet provide natively negatively correlated assets, which is why Ethena needs to tap into the perpetual futures market to find a hedge asset for its $stETH trade. In a nutshell, Ethena claims that the positive difference between the return of the underlying asset ($stETH—i.e. price dynamics plus staking rewards) and the cost of hedging, as characterised by the funding rate, more than compensates for the latter. Crypto’s search for uncorrelated uncertainty is not new—see vintage #9, and Ethena’s is just another, more sophisticated, attempt to expand crypto’s covariance matrix.

The basics of perpetual futures

Futures contracts have been widely used in finance to hedge long positions due to several advantages over other instruments: standardisation, liquidity, fair value representation, and reduced counterparty risk through margining. Margining mechanics also make futures contracts popular for amplifying directional positions—i.e. great sources of (a lot of) leverage. In crypto, perpetual futures (or perps) follow similar mechanics but simplify trading by not having an expiry date, allowing traders to keep positions (read leverage) open indefinitely.

For perps, funding rates help align contract prices to market conditions by increasing holding costs for one part of the trade vs. another:

Positive funding rate: longs pay shorts when the contract price is above the spot price—making the open position more expensive and putting pressure on the contract price until it eventually rebalances to spot

Negative funding rate: shorts pay longs when the contract price is below the spot price—following an inverse dynamic

Although the funding rate aims to close the gap between contract prices and spot prices quickly, divergences can and still still occur, leaving space for so-called basis trades. In a basis trade, a trader opens a position by purchasing (or selling) an asset and simultaneously selling (or purchasing) a futures contract of similar notional value for the asset. In a long-biased market where more traders are willing to pay to open long positions—i.e. to open levered long positions, holding both legs of the trade can consistently yield a positive return.

(2) Yield profile → Ethena’s claim goes a step further, asserting that funding rates are consistently positive (or not significantly negative) enough to provide a sustainable positive yield for traders. In the crypto market, this claim is supported by evidence: from 2021 to 2024, the basis spread on main crypto markets has been positive on a volume-weighted basis. Said differently, the crypto market generally exhibits a (levered) long bias that Ethena wants to package and exploit.

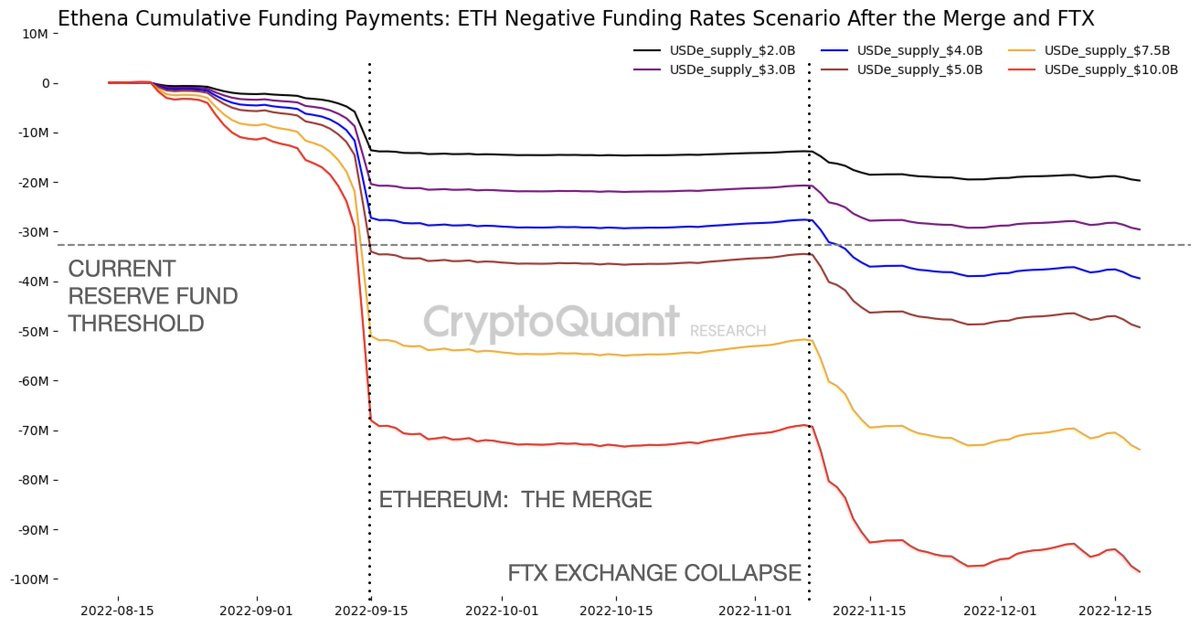

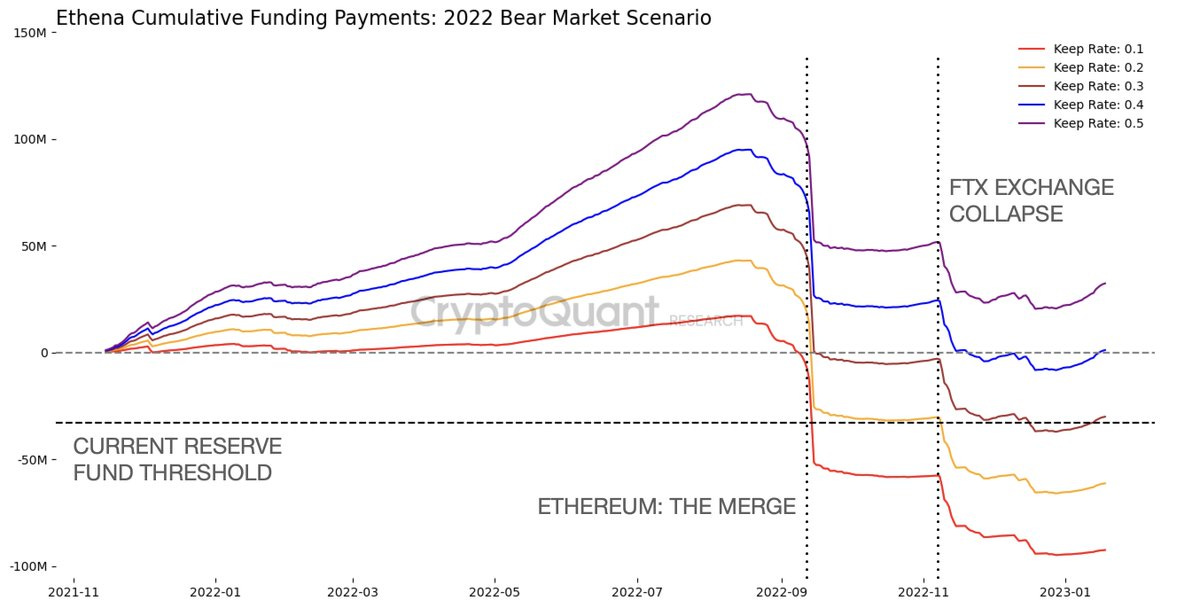

(3) Solvency → However, given Ethena’s claim about the ability to maintain a 1:1 tracking between $USDe and the USD, the variability (and not only the levels) of the return sources for the $USDe strategy is crucial. To dampen the (negative) volatility of these yield sources (such as the basis—funding—rate and other yield components) the protocol has implemented a reserve fund. This fund is supposed to step in during occasions when the combined $USDe strategy yield persists to be negative. Currently, (see Ethena’s dashboard) the reserve fund stands at c. $45m, or c. 1.26% of circulating supply. Julio Moreno (h/t) wrote a great analysis on $USDe’s solvency, including simulations on the resilience of the protocol’s reserve fund through backtesting. While the research is not updated, it provides an excellent framework for assessing protocol solvency. By examining drawdowns around significant historical events (such as the Ethereum Merge in September and the FTX collapse in the latter part of 2022) Julio’s analysis highlights key insights.

At a total $USDe float of $4b—today’s $USDe float is c. $3.6b, the cumulative funding rate drawdown during that shaky 2022 period would have been around $40 million, not too far from the current size of the insurance fund.

The futures market, however, has remained positively skewed for most of crypto’s young life. Based on another insightful chart provided by Julio, we can understand how the level of keep rate (more on keep rate later) is a dominant factor in understanding whether the replenishment speed of the reserve fund during normal (yet still positively skewed) times is sufficient to withstand massive and abrupt drawdowns. We can see how the backtested answer circa Ethena’s solvency is highly dependent on time frame and keep rate. The abrupt nature of the carry trade is indeed not a new phenomenon in finance, as it is the literature around its lack of resilience. The nature of the trade structure indeed requires speed, through-the-cycle foresight, and a manageable size. This is particularly important considering that the size of the $USDe strategy will likely negatively impact the underlying basis spreads.

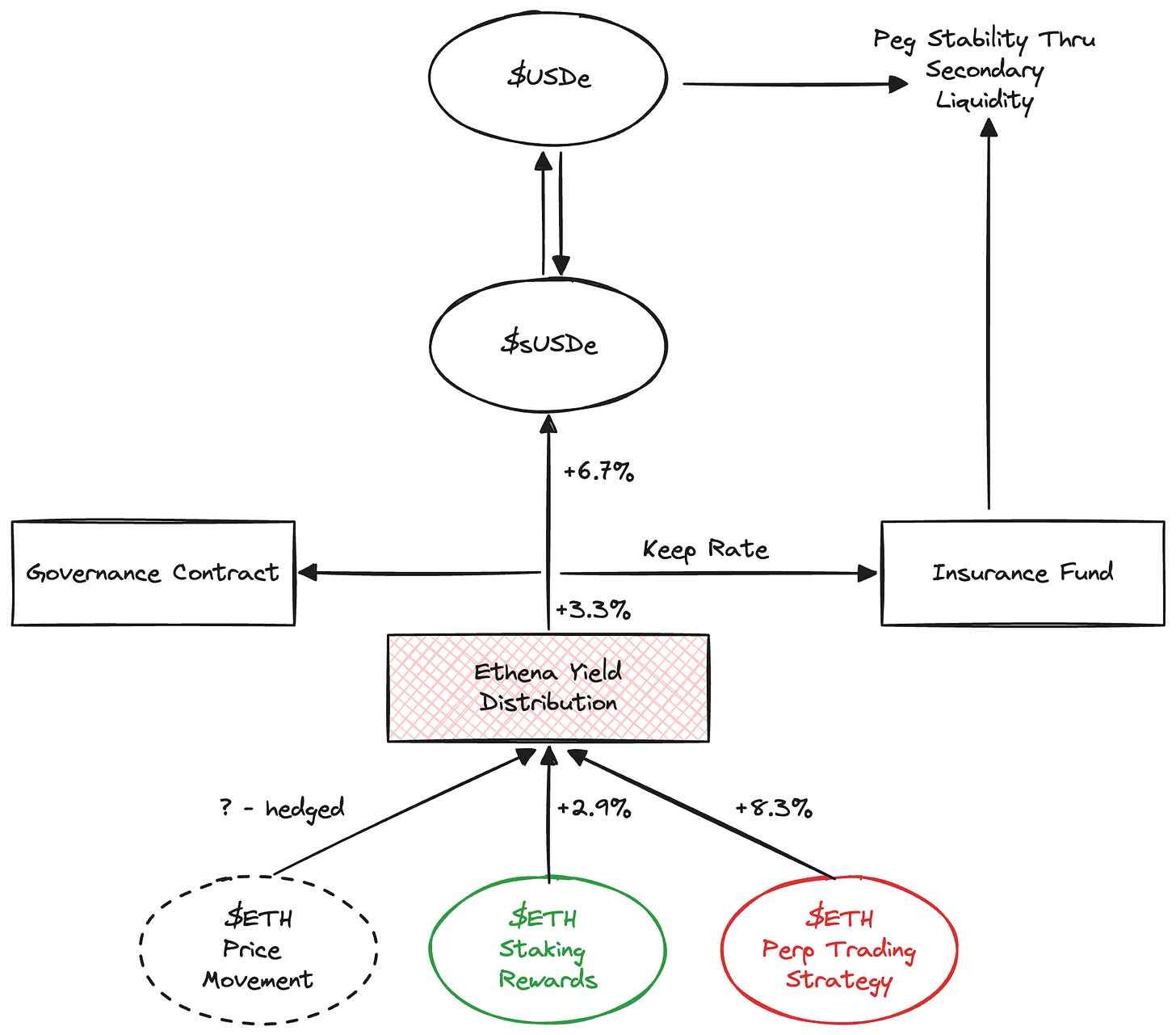

To finance the reserve fund, Ethena retains a portion of the underlying strategy economics—the Keep Rate. The remaining yield is distributed to $USDe stakers (i.e. $sUSDe holders) and ultimately to the governance contract. It is important to note that $sUSDe does not provide additional subordination to naked $USDe holders, but only receives positive or flat yield for the act of passive staking. The primary benefit of staking for the protocol, therefore, is reduced sell / increased buy pressure for $USDe, which potentially enhances peg stability—more on peg stability later.

According to this Dune dashboard, currently 45.2% of the total $USDe supply has been staked, earning approximately 6.7% in $USDe form. The chart below illustrates some of these flows. The numbers are taken at face value from Ethena’s website.

(4) Peg stability → Whitelisted minters and redeemers are the key anchors for $USDe’s peg stability, in a well-proven BtBtC framework, given their ability to mint and redeem $USDe for underlying collateral on a 1-for-1 basis. These participants can exploit arbitrage opportunities if $USDe trades below or above the peg by balancing the protocol levels with centralised and decentralised markets. Currently, there are approximately $70m worth of $USDe in Curve pools against other assets. While not perfect, peg has been relatively stable so far, especially considering the complexity of the structured strategy underneath.

As with other so-called stablecoins, or money in general, the goal is to expand the silent majority holding the currency simply for transactional purposes without demanding any yield. It is the cash in our pockets (which doesn’t grow) that generates the most profit for the printing press. The only way to convince holders of $USDe (and naked money in general) not to stake it is through its utility: money users want the most liquid, interoperable, and resilient asset to transact with. If money has that, or a perception of that, it can do without the yield maximisation component. The fact that more than 50% of $USDe is not earning yield, at least through the protocol, might seem like a very strong sign at first glance. However, this is crypto, and we always need to dig a bit deeper when it comes to capital movements.

WTF Do People Do With $USDe?

So where is the $3.6b float of $USDe? And also, why has only 50% of this float been staked for yield? These two aspects are closely connected, and point to yet another iteration of crypto’s well-managed captive liquidity capture game.

Whether $USDe is indeed a stablecoin or a well-executed tokenised structured product with some level of seniority and an effective supply-demand flow controller—more on this later, Ethena has successfully introduced a profitable trade and an additional source of leverage into DeFi. It is not surprising that in a risk-on environment like DeFi, the most dominant protocols (i.e., those controlling the most liquidity) have been paying attention to Ethena.

Enter the Maker > Spark > Morpho > Ethena tower of farming.

Currently on Morpho, the newly crowned leader among permissionless lending markets, $USDe and $sUSDe represent four of the five collaterals with the highest supply, amounting to a combined supply of around half a billion dollars. The largest, a $166m $sUSDe/$DAI pool, currently charges borrowers 11.24% (with an 86% LTV) and remunerates liquidity suppliers at 9.76%. It is evident that the passive rate is not sustainable given the current return profile of $sUSDe, yet utilisation is still pretty high. This is even clearer for the $116 million $USDe/$DAI pool, where borrowers are charged 7.73% to borrow a non-yielding asset like $USDe.

These pools have been deployed by Spark, Maker’s captive lending market, which also provides the liquidity for the $DAI leg into the pools. According to makerburn.com, Maker is currently deploying over $1b to Spark through a D3M model (designed by the same Sam who currently runs Spark) with a debt ceiling of $2.5b. Maker is currently accruing approximately 8.6% annualised fees on the credit line, while Spark charges 9% to borrow the same $DAI. A chart can help make sense of the economics and credit enhancement across the liquidity stack.

It is evident that there is currently a negative spread between what Maker pays out to $sDAI holders via the DSR and the underlying weighted yield captured away from Ethena. Also interesting that the only protocol capturing some sort of positive structural spread is Spark. This is particularly significant given that the Ethena trade is one of the highest-yielding assets in Maker’s collateral pool and represents 20% of the protocol’s total collateral. Additionally, credit enhancement is slim, meaning that Maker’s surplus buffer of approximately $50 million should be able to absorb negative spreads and potential slippage.

Those who have spent enough time in crypto will easily understand how the gap has been bridged. Starting from the end, Morpho has a token reward program—although not currently deployed for Ethena-based collateral, Spark has an upcoming airdrop program, Maker has its own infamous endgame that keeps changing at a rate faster than Boris Johnson’s stance on the number of kids he has. At the foundation of it all lies Ethena’s own reward/ point/ airdrop/ farming/ restaking program.

Ethena’s $ENA → Ethena’s reward program is complex, and it’s beyond my interest to provide a detailed explanation of its intricacies or to offer a guide for airdrop farmers looking to maximise their returns. However, the program’s aims are clearer. It provides incentives (shards, another iteration of crypto points) for staking $USDe, offering 5x more for holding naked and non-yielding $USDe, and 20x more for providing locked liquidity across Curve’s pools. Shards have a purposely opaque correlation with future $ENA (Ethena’s governance tokens) rewards. $ENA can be locked or restaked for additional rewards. Ethena’s directional intentions with the incentive program are clear:

Increase general holding of $USDe

Skew holding towards naked $USDe to make staking yield more competitive—especially given the compression of the basis trade and the depth of the liquidity stack that yield needs to feed

Increase demand for $USDe and enhance liquidity of $USDe pairs to sustain the peg stability of the so-called stablecoin

Boost the perceived valuation of $ENA through a virtuous TVL-led cycle and reduce sell pressure via restaking

As a reference, $ENA currently has a market float of approximately $800 million and a fully-diluted valuation of over $7 billion, or 2x TVL—not little but significantly down from its peak.

Fixed income vs. equity → Once again, during yet another crypto bull market, fixed income yields continue to be subsidised by equity-proxy trades, which anchor liquidity providers’ expectations on the latest venture valuation rounds for crypto projects. The correlation between token valuation and face value TVL helps reinforcing the virtuous cycle. Whether these are good uses of capital from an equity investment perspective goes beyond the scope of this post, and frankly the patience of the author.

Ethena Not At Face Value: Is It a Synthetic Dollar, Is It an Internet Bond?

While we have spent the majority of this DR entry digressing and dissecting Ethena’s strategy structure and its risk-reward DeFi implications, it is actually the protocol’s philosophical claims that are more interesting to me as a money researcher.

Is Ethena’s depiction of $USDe as a synthetic dollar, or internet bond a fair one? While these definitions do not completely overlap, they point to the creation of an asset ($USDe) that mimics certain properties. What are those properties?

What makes a good synthetic dollar → The synthetic dollar definition suggests that $USDe aims to replicate the characteristics of USD through a combination of ingredients that do not appear in the original asset’s recipe. Beyond the obvious one—i.e. the local price stability relative to the USD, this implies that $USDe intends to embody the main properties of the world dominant (dollar-denominated) money market instrument. Money markets are awkward beasts—see #59; a Money Market Instrument is (MMI—from #59) a short-term / low-risk way for one side to temporarily park liquidity and for the other to obtain short-term financing at very effective rates. For this reason, MMIs are founded on the concept of no question asked—NQA-ness, or satisfactory opacity: you don’t care what’s backing a MMI and you shouldn’t, because the instrument is so deeply in the money to make any default probability on the instrument negligible for the holder. The centrality of NQA-ness suggests also that (a) yield optimisation (read price discovery) is not one of the key characteristic of MMIs, and (b) certain assets are better suited, from a capital efficiency perspective, to structure good MMIs. Point (b) has been the main difficulty faced by crypto-backed USD proxies so far: the volatility of the underlying asset (measured in USD) is so high that achieving deep in-the-moneyness becomes extremely capital inefficient. The alternative, unfortunately, is the adoption of a sophisticated underlying structure (sometimes insourcing other return flows and some other times overlaying complex supply-demand algorithmic mechanisms) that does indeed make price discovery extremely important. Based on this definition, and Ethena’s structural characteristics described above, $USDe is not a good synthetic dollar.

What makes a good (internet) bond → What does the term internet bond intend to convey? A bond, first and foremost, is typically a senior liability claim over (cash flows of) an underlying assets. The yield of the bond (whether through interest coupons or repayment) is less volatile from a risk-adjusted perspective than the yield of the underlying asset. If we assume that price incorporates this information, a bond has a less volatile price and, as a consequence within a CAPM arbitrage-free framework, a lower return. That extra juice, or yield, is typically passed to equity holders. If you see a bond having a higher yield than the underlying asset, then either it’s not a bond, or there’s some extra leverage and liquidity issues hidden somewhere. Estimating $sUSDe’s risk-return volatility versus the underlying (unlevered) asset is challenging, especially considering the implicit leverage added in the basis trade leg. The level of seniority, guaranteed by the reserve fund overcollateralization, is not as significant from a through-the-cycle perspective. Ultimately, I don’t think $USDe / $sUSDe qualifies as a true bond either.

So, what is Ethena? Ethena is a phenomenally-elegant and well-executed Ethereum/ Bitcoin equity structured product with some level of seniority, a not insignificant return leakage to Ethena’s tokenholders, and in exchange some extra juice in the form of equity $ENA optionality. It has also been profitable enough to guarantee a tailwind for over $3.6 billion of kind-of-double-spent TVL for a set of protocols.

Ethena was definitely the right product at the right time. But a synthetic dollar, or an internet bond? No.