This is another issue of Dirt Roads. Those are not recaps of the most recent news, nor investment advice, just deep reflections on the important stuff happening at the back end of banking. The time we are sharing through DR is precious to me, I won’t make abuse of it.

There was a time statesmanship wasn’t measured inside the passive-aggressive rooms of Davos or the G-whatever. There was a time constitutionalists and composers of national anthems were still in their twenties and thirties, jugged litres of whisky, and got portrayed with dark black beards and bare chests. Before politicians turned fat blood-sucking bureaucrats, we were rallied by an old vintage of gangster-poets. There was a time I might have liked to be a statesman. And that time is back.

While grey-haired men are filling their mouths with ancient post-fascist rhetoric trying to fool osteoporosis and andropause, outside of the buildings made of marble and spiderwebs a handful of pioneers is reinventing modern society and the crudest economic systems. They aren’t liked by the FT or Bloomberg, but they do not give a damn or, most probably, they don’t even know. Modern patriots wave monkeys as flags, pile up incommensurable wealth in shadowy wallets, and use ties only around their foreheads as Rambo taught their parents during hackathon afterparties across the world. They used to talk advertising and gaming and chatting, now they rhyme money and politics and ethics.

It is now the time again for the drifters, the crazy ones, and the visionaries. It won’t last for ever. Let’s make it count.

Money Talks

I know that you know that I know that you know that in Dirt Roads we are obsessed about currencies. You might be too, but in the outside world not many others care. They don’t because currencies work so well, and we do exactly for the same reason. I, personally, care about two aspects of currencies:

Top-down power of allocation: how does the government control the amount of a certain currency that gets distributed within a system?

Bottom-up power of illusion: how’s it possible that users are so chilled in keeping all their lifetime savings in the form of a certain currency?

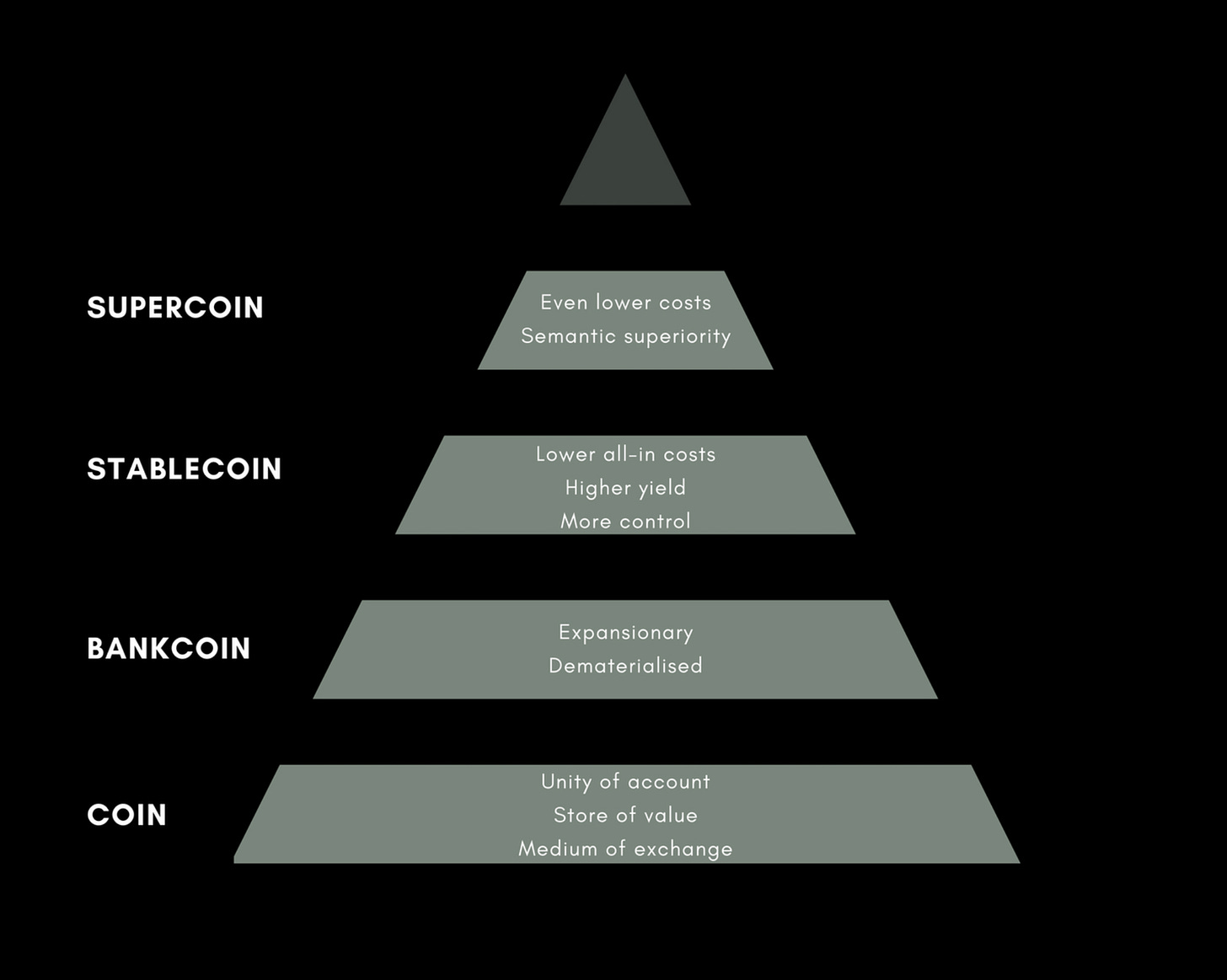

Most of the stuff Dirt Roads has been dealing with refers to point n. 1. Currencies are not only unityofaccountstoreofvaluemediumofexchange 🥱, they are super powerful resource allocators, and it isn’t surprising we care about that aspect a lot.

A summary → In A Taxonomy of Currency I tried to construct a monetary pyramid that started from hard coins (those minted by central banks) and added bankcoins (those produced out of thin air by the institutions that have a license to do so - i.e. commercial banks) and stablecoins - primitive digital currencies native of the blockchain. A Taxonomy of Currency (II) pushed the framework further with the addition of supercoins, i.e. digital currencies that aren’t anymore primitive, but instead incorporate a set of more and more complex features that, with time, are inefficient to be mastered at a primitive level. Nobody writes programs in machine code, ask yourselves why. The monetary pyramid is getting more and more complex (here’s another article if you can’t sleep) but the key characteristics remain: central governments maintain fiscal control over the economy and leave to private systems the allocation and distribution of this spending power.

The fact that all the largest stablecoin projects are anchored on the value of a recognised centralised currency is not coincidence. Hint: it’s in the name. None of those projects has had yet the ambition to build another pyramid from scratch wiping out its base, i.e. the reliance on a physical central bank, in the process. Keep in mind that such reliance can be physical, like in the case of Tether or USDC, or constitutional by mandate, like in the case of the DAI or TerraUSD. It’s easy to see why: governments collect taxes, facilitate the system through a highly complex bureaucratic apparatus, write regulatory codes, and have pretty solid armies. Beat that.

But only one of those stablecoins, Terra, might have the ability one day to go its own way and abandon such reliance. We will start exploring why, and how.

Monetary Finance: a Short Story of the Peg

Terra reminded us that we can look at a sovereign economic system the same way we look at a company.

Excusably horrible two-minute corporate finance revamp → In corporate finance a company’s total value, that of all the assets it owns, is called enterprise value. A company’s EV can be split into debt, the value of all contracted liabilities, and equity, which is what remains after everybody has been paid out. Those values fluctuate for mere arithmetical reasons (a company issues more debt, repays some, repurchases stocks, invests in its asset base, or simply grows or shrinks) but also for volatility reasons. Another corporate finance reminder: the present value of something is the summation of its future expected flows divided by a factor that is proportional to their volatility - future flows that are certain have a higher value than the same but with a higher degree of uncertainty. If the mere prospect of a company to generate cash flows starts shaking, the first value to get hit is that of its equity, since equity holders are those that get paid last and hence suffer of higher volatility. The ups and downs of equity valuations we observe in markets is almost in its entirety connected to those changing expectations about cash flows, i.e. to changes in the volatility assumptions, rather than to arithmetical events.

A corporate finance view of an economic system → The same thinking can be applied to a sovereign economic system. The whole economy’s EV is the present value of what it produces - GDP is the most used measure, and the value of its debt is the market value of its monetary base. The equity value is basically what remains and it is quite difficult to measure. Let’s focus on its monetary base, or broad money. The value of broad money and of its atomistic unit of measure, currency, goes up and down all the time. We simply (i) do not in most cases really care since we base everything we do or even think in such denominator, (ii) or on the other hand are kind of used to seeing currencies going around in circles against each other.

Nevertheless, volatility of currency matters. And the smaller the economic system the more it does. Nobody in their sane mind would hold anything in an extremely volatile currency unless in a gigantic and completely autarchic economic system, where you don’t need to interact with others. That is why most smallish or highly volatile (e.g. commodity-based) economies resort to a well-travelled trick: they peg. Caveat, the peg is addictive.

The Prestige

Fixing the exchange rate of a currency vs. another, more stable, sibling, means getting rid of a big chunk of domestic currency volatility. And, all other things staying the same, lower volatility translates into higher value. Does this then mean the value of a whole economic system can be increased simply by pegging the currency to a larger and more stable one? Or, said in other words, can we really get rid of volatility so easily?

The answer, unsurprisingly, is: no way. Rather than vaporising volatility into thin air, a peg shifts volatility from an economy’s currency, aka debt, to its equity. It happens all the time although you cannot see it, until it’s too late. A domestic currency depreciates against the pegged pair, so treasury raises funds somehow to buy that currency in the open market and increase its price. A currency appreciates, so treasury buys the sibling with its currency reserves. There are a lot of other tricks, but the bottom of the story is that in a pegged system the country’s fiscal policy cannot be independent from its monetary policy.

What it means, in finance terms, is that the volatility of the currency is transferred from currency holders to the system’s equity holders: the treasury, the domestic companies, the citizens. The system works out well, until it doesn’t, when the economy needs something that the fiscal policy cannot provide, and the peg becomes unsustainable. I spend a lot of my time in South America, the promised land of the pegged currency blowups. They know the drill. The system’s volatility has always been there, brewing, but you couldn’t see it, couldn’t see it, couldn’t see it, until it blew up in your face.

Why is Terra so interesting? Because on Terra, you can.

The Terra-Luna System

Terra is a sovereign economic system. Terra is a programmable blockchain protocol aimed at issuing, managing, and manipulating financial value. Terra is like Bermuda.

The Terra system has its own currency, $USDTerra, implicitly pegged to that of the biggest economy it interacts with, $USD, and its own governance token, $LUNA. Said in computer engineering jargon, the Terra Protocol runs on a Proof of Stake (PoS) blockchain, where miners stake its native token $LUNA to mine $USDTerra transactions. $LUNA represents the mining power of the network.

The fact that $USDTerra stablecoin is pegged to $USD favours its use across the DeFi ecosystem. Given that we are in an expansionary phase of such ecosystem, usability is key for the survival of a currency. Expansionary times are also the most volatile ones, so where does such pampered currency volatility go? The question is the same we were asking before for TradCountries, the difference is that now we can see and measure in a way we couldn’t before.

Counteracting contraction forces → During a contraction, when demand for $USDTerra decreases and its value goes below the peg, Terra mints and auctions mining power $LUNA to buy back $USDTerra, supporting its price. The volatility of the currency is shifted to miners. In corporate finance terms, this means that in order to stabilise the value of the system’s debt, the system increases its (treasury) equity with the effect of diluting that of miners.

Counteracting expansionary forces → During an expansion instead, when demand for $USDTerra increases and its value goes above the peg, Terra uses currency reserves to buy back $LUNA, de facto injecting more currency in the system and diluting its price. The volatility of the currency is shifted to treasury. In corporate finance terms, this means that in order to stabilise the value of the system’s debt, the system decreases its (treasury) equity with the effect of accreting that of miners.

As for any pegged system, the mechanism works only if the system’s equity remains able to absorb such high volatility. As for any asset, volatility can be justified in the eyes of an investor/ miner only if the returns of such system are high enough.

So How Does the Terra System Make Money for $LUNA Holders?

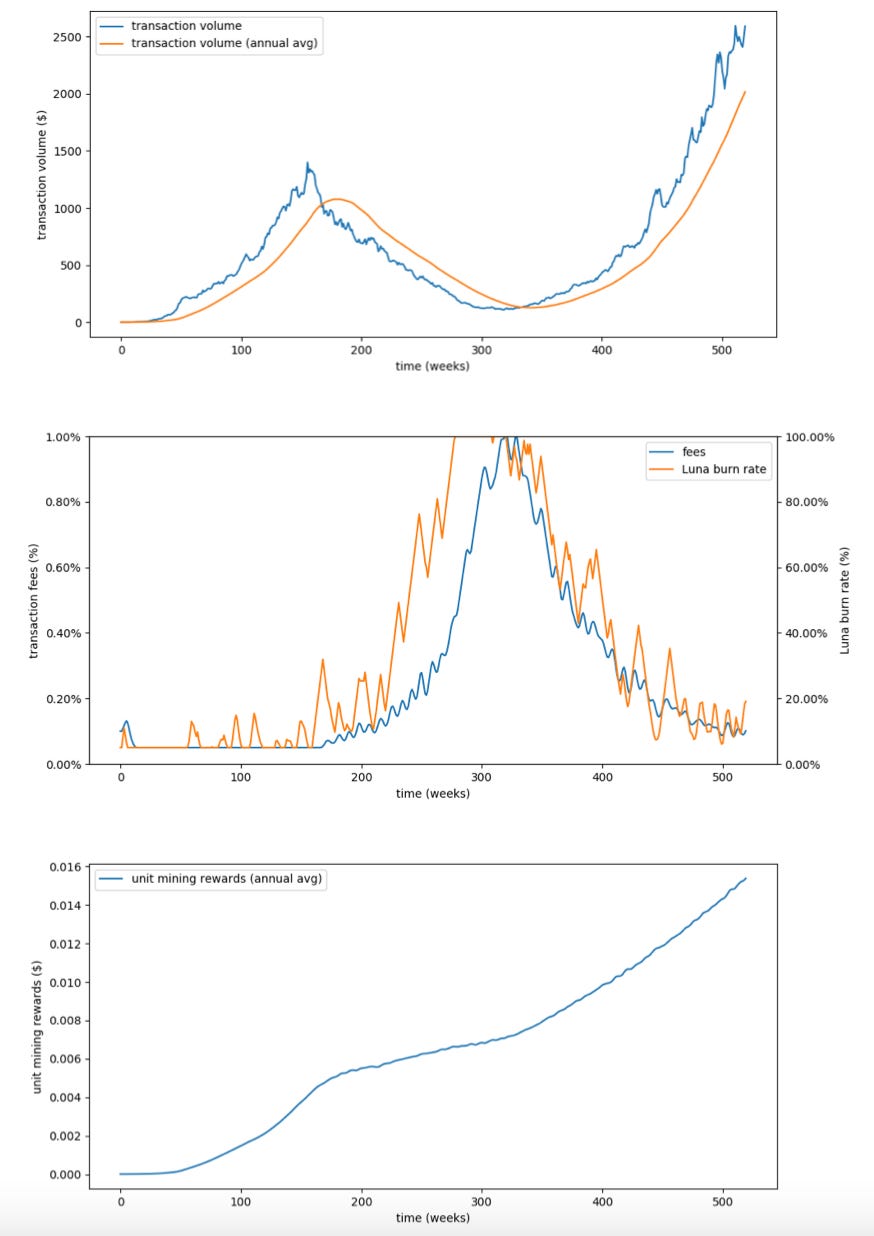

Terra miners are compensated with transaction fees and seignorage accretion coming from the $LUNA burn discussed before - as usual you can go into the details in Terra’s whitepaper.

The Terra crowd is aware that, in order to have a stable and growing participation of miners in their ecosystem, and sustain the stability of the currency, those miners’ rewards should be kept as stable as possible - while also growing. As for other well-minded states, they use policy levers.

Taxation → On the one hand, transaction fees and seignorage parameters are kept programmatically dynamic, in order to counterbalance the volatility of the underlying system’s economic activity.

Economic growth → On the other, the system’s economic activity is incentivised through an interventional, growth-driven, fiscal policy. Terra offers a dApp platform oriented at building financial applications that use $USDTerra as underlying currency. In addition, treasury allocates resources derived from seignorage to some of those applications in the form of grants.

Currently, Anchor - saving, Chai - spending, and Mirror - investing, are the most relevant dApps built within the Terra ecosystem. Each will require dedicated time on Dirt Roads. They all run on the PoS-based Terra blockchain, use USDTerra as a currency, and have their own sovereign tokens and communities. They are currently the most powerful conglomerates of Terra-land. It isn’t surprising it was Mirror, with the proposal of facilitating trading of synthetic real-world securities on-chain, to attract love from the SEC.

The surprising thing was that Terra hit back. Crypto economies are getting organised, and the Terra ecosystem keeps expanding - with $LUNA token holders controlling the power of proposing and voting changes. Terra is an autocratic, interventionist, economy gravitating on the shores of the largest economy of the world, the USD-backing United States of America. But Terra is aggressive, and is ready to protect its independence by acting in accordance to international law standards while trying to expand its footprint and reliance in favour of other sovereign superpowers.

Terra is Cuba.

Innovating is a communal effort. If you have great ideas you want to explore together, great companies that should be on Dirt Roads radar, or topics you would like to co-author on DR, please feel free to reply to this email or contact me on Twitter.