# 16 | Full-Stack Central Banking

Trying to Reform the Monetary System Without Mastering the Whole Stack Is a Very Silly Idea

This is another issue of Dirt Roads. Those are not recaps of the most recent news, nor investment advice, just deep reflections on the important stuff happening at the back end of banking. The time we are sharing through DR is precious to me, I won’t make abuse of it.

Unstoppable Forces Meet Immovable Objects

Ultimately, however, it takes a system to beat a system. Saule T. Omarova

The traditional monetary configuration, or so-called franchise system1, is in deep trouble. Following the 2008 Great Financial Crisis and the 2020-? COVID-19 one, the public-private arrangement ruling the effective distribution and allocation of sovereign currency has been struggling. Strangled by, on one side, urgent and gargantuan public stimulus needs and, on the other, a sclerotic approach to innovation, traditional commercial banking has progressively lost its edge. Never before has the sector had to face so brutal attacks.

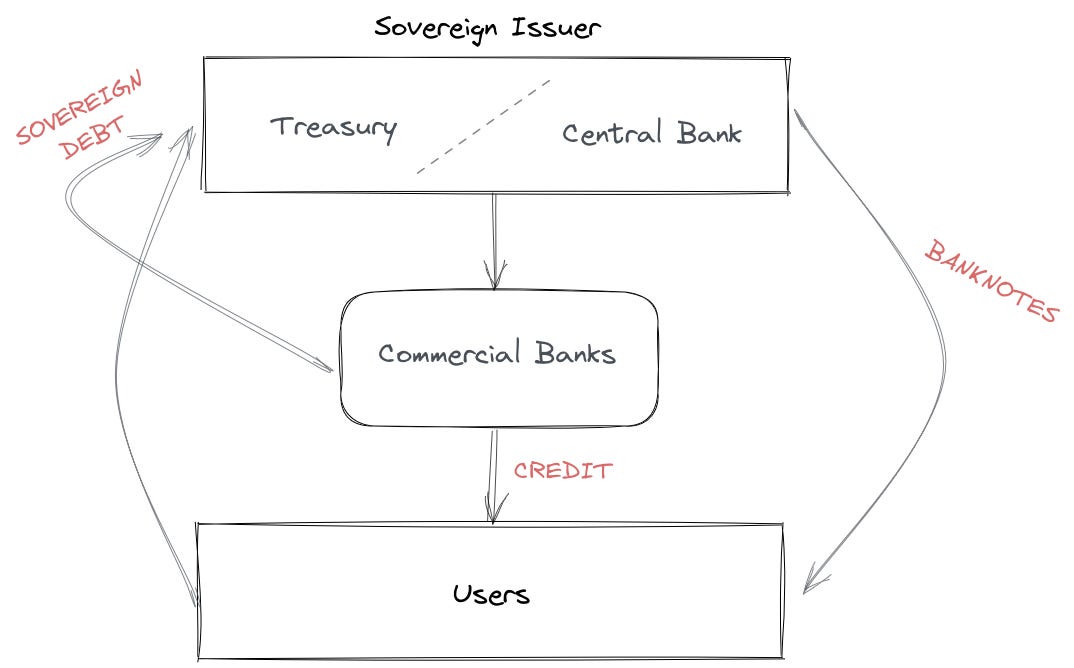

It hasn’t always been like this. For the thirty-five or so years separating Bretton Woods and the GFC, the franchise system has actually worked pretty well. Central banks maintained a monopoly in modulating monetary supply, and commercial banks engaged in the distribution and, most importantly, allocation of such supply (via lending) to the users. The three tiers remained connected via a set of mechanical and regulatory requirements allowing the sovereign state to steer the economy and keep the overarching risks in check.

By the early 2000s things changed. A description of what did goes well beyond the scope of this weekly post, but the point is that central banks found themselves more and more engaged in doing the monetary allocation function traditionally reserved to the commercial sector. The COVID-19 humanitarian crisis exacerbated this further: in the US, the FED created two corporate facilities - the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility, alongside the Municipal Lending Facility, de facto providing businesses and institutions with a direct access to the central bank’s balance sheet, and bypassing the traditional credit underwriting role of commercial banks. It was only natural that those same central banks started to think about expanding their role on the monetary distribution side as well, incentivised by the emergence of new decentralised intermediaries. The result was a global rush to prototyping Central Bank Digital Currencies (here).

As we have already argued on DR (here), a civil war for money is on. Notwithstanding the many efforts from regulators to safeguard the role of commercial banks in the monetary ecosystem of the future - genuine or not, it is undeniable that power is shifting. The focus of this post is not to argue who will lead this emerging system, but to try and guess how it could look like. The blueprint could act as a useful map to navigate the innovations happening in the universe of value transfer.

The New Monetary System(s)

So how could the new monetary system work? Let’s dig.

A New Monetary Configuration

A sovereign issuer of some form would probably still sit at the apex of the monetary food chain. Such issuer would be the sole monetary authority, linked to a sovereign community (a state, a federation, a corporation, a DAO, etc.) with control over a set of tangible and intangible assets backing the monetary supply. The issuer could distribute and allocate coins to users in two distinct ways:

Direct-dropping those coins to users - based on a set of parametric decisions

Allocating additional coins through a set of qualified intermediaries

Mechanism (1) → An authority decides to airdrop coins (CBDCs, stablecoins, any other form of value storage) to community members based on its own decision-making mechanisms. In CBDC jargon, this is equivalent to allowing all citizens (and businesses) to open an account at the central bank where to deposit and see deposited their coins. Given the direct link between the sovereign and the users, mechanism (1) encompasses both traditional monetary distribution and monetary allocation function. In the case sovereign issuers would opt for retaining full control of monetary allocation, Mechanism (1) alone would be sufficient to make the system complete.

Mechanism (2) → Centralised monetary allocation, however, is a difficult beast to tame. It is prone to inefficiencies and moral hazard due to operational complexities and information asymmetries. Imagine a central authority (printing money) deciding whom to finance, for how much and how long, and you can already start picturing a long list of reasons why the system would not work. It is why acting via a list of qualified intermediaries, as described in mechanism (2), could help. This is somehow similar to what happens today in the franchise system via the commercial banking sector. The difference, however, lies in how this would happen. Compared to their role in the franchise system, credit intermediaries would lose the monopoly on customer deposits; their function, therefore, would become the mere aggregation and pass-through of eligible credit assets. Although this aggregation function wouldn’t be exclusive of qualified intermediaries, only those qualified would have the ability to pledge some (those considered eligible) to be financed centrally by newly printed money. In this way, the sovereign issuer would delegate to intermediaries most of the heavy lifting in identifying and pricing good credit, while retaining full control of all parameters of eligibility.

We can see how, in this new configuration, a sovereign issuer would enhance control and visibility of both monetary manipulation and monetary allocation without compromising in efficiency. But a sovereign issuer shouldn’t retain the monopoly of the use of the coins minted. In the same way USD banknotes can be used in ways that are not necessarily compliant with the US legal framework, users could still engage freely in an infinite number of use cases that involve value manipulation while outside of the sovereign borders; in doing so, however, they wouldn’t benefit from the leverage provided by playing within the qualified ecosystem.

The Job of a Financial Intermediary

Qualified intermediaries, as described above, are an abstract category more than anything else. Some kind of intermediary has always existed in complex systems, and the fact that a new breed might emerge today is simply related to the fact that we have now technologies at our disposal that weren’t with us until recently.

On the extreme, intermediaries could simply be aggregators of ultra-safe and standardised assets offering users some basic functionalities and yield. This is Circle’s USDC way - a USD 31.1b money market fund with full reserving and a great suite of compatible services within DeFi. Although this Buffett-esque play (creds to Porter) might very well be profitable for Circle by aggregating a flow of investable liquidity with negligible or even negative cost of capital, the impact of such aggregators on money allocation would be limited, and the risk of being replaced by the airdropped CBDC high.

A more interesting set of intermediaries are those we can call algorithmic conduits. A sovereign issuer would whitelist a set of qualified assets (collaterals) as eligible to be financed through the discount window, plus a set of parameters, and leave the ultimate users pledge and manage the coins minted independently. This is the case of MakerDAO’s vaults - if we exclude Real-World Assets vaults. Users post collateral (e.g. ETH) in a Maker vault and get freshly minted DAI in exchange. They are exposed to the risk of liquidation and need to monitor the parametric changes that the protocol vote on. If we exclude algorithmic stablecoins (that would require a separate discussion) each crypto-stablecoin represents a different take on the qualified intermediary concept.

Intermediaries of this new monetary configuration can be stacked one on top of the other. Let’s look at the example below.

A (non-qualified) intermediary of some kind proceeds in aggregating assets within some sort of structure. Those could be on-chain collaterals - e.g. ERC-20 or ERC-721 tokens, as well as off-chain contractual or reputational agreements. Simultaneously, such intermediary stacks a set of liabilities to fund the purchase of those assets - e.g. some (junior) underwriting capital coming from the intermediary itself and liquidity coming from liquidity providers. This can be done by anyone, in any form, for any type of asset, while sitting outside of the confines of a sovereign monetary system. In order to provide some margin of safety to the liability holders, the intermediary needs to retain a buffer, i.e. a difference between the perceived value of the assets and that of the liabilities. Unless there is some lender of last resort, there is no way out of the overcollateralisation problem. This is the case of most lending rail providers in DeFi nowadays, where liquidity is aggregated in the form of USDC, USDT, or DAI, by firms such as Goldfinch, TrueFi, and Maple, without the authorisation of Circle, Tether, Maker, or anybody else.

Although each of those firms adopts a different model, they all attempt at aggregating claims on value for their investors while trying to align everybody’s incentives around a common goal.

Goldfinch → here.

TrueFi → TrueFi went the centralised way, by vetting borrowers who want to request for a loan and allowing liquidity providers to earn interest on their own native stablecoin, the TrueUSD. In doing so, they have been trying to solve the overcollateralisation conundrum by integrating, from the bottom, both monetary distribution and allocation. Given the fully-reserved nature of TrueUSD, however, money distribution is limited by a strong peg on the USD, making monetary expansion impossible to handle. This doesn’t seem to worry lenders, and TrueFi has so far originated c. USD 551m across three pools - USDT, USDC, TUSD.

Maple → Maple stands on the middle ground. Rather than taking an active role in scoring or vetting new borrowers, Maple is stepping back and selects instead which sponsor they want to onboard on their platform, leaving those sponsor do the work. In Maple, Pool Delegates develop their own investment and underwriting policy and launch a pool to aggregate assets from a set of borrowers they select. In order to signal the market that their incentives are aligned with others, they are also stakers of junior first-loss capital in those same pools. Lenders instead provide additional, senior, capital to the pool, participating passively to the asset yield. Maple has currently c. USDC 180M of committed capital, mostly drawn. The Maven 11 Capital pool (see below) has 15 active loans and has earned c. 28% APY for the liquidity providers (in the form of both USDC and MPL governance tokens) since inception. In the same period it has generated > USDC 500k fees for Pool Delegates and Treasury. No loans have defaulted so far, so we might need to wait a little longer to see how the (slim - USDC c. 2.7m) junior piece would hold up without strong on-chain collateralisation.

Stacking Intermediaries One on Top of the Other

In a stylised form, Maple’s modus operandi is similar to the scenario described above, although with most collateral assets sitting off-chain. This last aspect, i.e. the absence of full-recourse collateral sitting in a smart contract, might limit composability within the DeFi ecosystem. It doesn’t seem that this is limiting Maple’s growth, so do composability really matter after all?

I think it does. The further you are from the source of the returns, the more challenging it is to assess risk. With a trusted access to full-recourse collateralisation, lending structures could get arbitrarily complicated without amplifying risks for the marginal investor. We could construct more efficient structures, appealing to a diversified set of investors, by stacking layer after layer. A financial intermediary like Maple could, for example, build a super senior position, apply for eligibility within a sovereign monetary system, and finance it via the discount window enhancing leverage and returns for the whole stack. The liquidity and underwriting capital LP tokens themselves could be used with unlimited creativity. Within DeFi, this could be done parametrically and programmatically, without losing visibility and control of the credit creation mechanism. Composability, yet again, matters.

But who will be this sovereign issuer of last resort? Will it be a crypto-native currency issuer like MakerDAO, or someone Maker-like? Or the FED through a universally-accessible CBDC? Or Diem? Or a consortium of governments like the IMF? I think it is too early to tell, and in some sense it doesn’t really matter: you can always stack a new lender of last resort on top of the one previously at the beginning of the chain, without compromising the whole stack.

There is a catch. When stacking one financial brick after another things get very complicated very quickly. Monitoring systemic risk within the franchise system was a much more straightforward job, with only few aggregators (namely, regulated banks) incorporating a big chunk of the roles that are now disorderly distributed instead. Those were the golden years of macro-prudential banking regulation. The real trade off, however, is not between risk and no-risk, but rather between observable and non-observable risk. That is why today any attempt to reform the monetary system cannot leave aside a deep understanding of the full-stack transmission and allocation mechanisms, being TradFi or DeFi. If a tree falls in the forest of the financial system it always makes a noise, even if no-one is listening.

Innovating is a communal effort. If you have great ideas you want to explore together, great companies that should be on Dirt Roads radar, or topics you would like to co-author on DR, please feel free to reply to this email or contact me on Twitter.

This definition, as many others in this post, has been inspired by Saule T. Omarova’s The People’s Ledger: How to Democratize Money and Finance the Economy. Although I do not agree with all the conclusions brought forward by the author, and I try to push the framework further, I owe her spiritual recognition for connecting so many dots so effectively.

Out of many DR posts, this one best clarified for me what exactly you are trying to build through M^0. Thank you.