# 43 | First Principles of Crypto Governance

Designing Gonzo-Mathematical Governance Mechanisms for Systems of Irreducible Uncertainty

My family dog, Leo, hates vets to the point of barking at the sole sight of the road sign pointing towards the small town where the vet practices. He hates vets because vets mean needles and needles hurt. Apparently, in the vast vocabulary available to Border Collies there is no space for symbolic reasoning — he cannot comprehend why the pain of a needle might actually protect him from developing way nastier and more painful diseases. Needles mean pain, and pain is bad. Yet, he goes, entering through the sliding doors with the ears down and a pair of wet eyes that seem demanding my father “I know we love each other so why are you doing this to me?” And that is the whole point: in the incomprehensible world of the humans he lives in, Leo chose to trust the heuristic that, since his family seems to have always acted in his interest, any request (even the painful ones) might be part of this loving and caring mutual agreement. Dogs and humans have been friends for thousands of years, and in the vast majority of cases that heuristic proved to be a useful one, and so it perpetuates.

The Heuristic of Benevolence that is so pervasive between the founders-masters-controllers and the community members of crypto decentralised organisations might have similar origins. You-guys-have-made-me-or-others-immense-money-so-far-hence-I-shouldn’t-ever-doubt-your-pure-intentions. It might be for the same reason that the same Heuristic of Benevolence turns into a Heuristic of Suspicion towards anyone who hasn’t participated to the construction of the community in the first place, i.e. the outsiders.

The problem of heuristics is that they are easy to trick.

Oh Governance, Dear Minimiser

Last week’s Dirt Roads dealt with the recent governance cycle at MakerDAO. Three open questions were included at the end of it:

Do we believe in Maker’s censorship resistance, based on the existing governance mechanisms and token distribution?

Do we believe Maker to be a truly decentralised organisation when a group of (arguably) concerted parties has had enough voting power to outvote so many institutional participants?

Do we think Maker is structured to effectively tackle use cases (and borrowers) that bring even a minimum level of complexity and opacity?

The three questions could have been summarised into one: do we think that the dominant governance frameworks of crypto protocols can (locally) incentivise benevolent behaviour while tackling complex tasks? My gut feeling is that the answer to that questions is simply “no”.

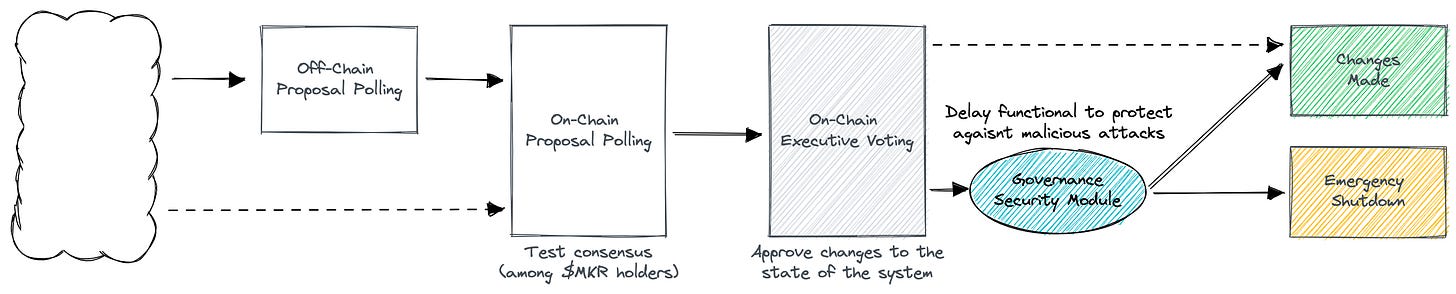

In the case of Maker, as in that of many other crypto projects, governance tasks are uniformly distributed to the holders of a governance token — $MKR. Details about Maker’s governance set up can be found here, but more generally holders of $MKR can vote on changes of the protocol — with proposals instead submittable by anyone. The proposals are voted on along the flow simplified below.

Arguing about the most efficient distribution of roles or alternative casting mechanisms goes beyond the spirit of this post. What interests us here is that the architects of Maker’s governance framework recognised the risk of a malicious governance attack, and in order to oppose it they included a Governance Security Model that has the function of delaying the implementation of specific proposals — allowing $MKR holders to gather enough consensus to call for an emergency shutdown followed by an ordered unwinding of the protocol itself.

The Optimistic Governance school pioneered by Aragon and Optimism bootstrapped this concept by assuming all proposals are voted in, unless challenged on court within a certain timeframe. Those efforts, laudable, remain effective in an environment where the outcomes of each decision are obvious, measurable ex ante, or with immediate effects. With the expansion of DAOs’ ambitions beyond ossified and clearly defined boundaries, and towards tasks as complex as the on-ramping of real-world credit through sophisticated structures, it becomes clear that not even an optimistic window of challenge can be enough to protect against malevolent attacks.

The issue of non-reducibility → Originally, most on-chain governance had to face very simple decisions: whitelist or not an ERC-20 token, increase or decrease a parameter, activate or deactivate an oracle feed. Governance mechanics evolved to satisfy this need, and blockchain tech allowed a more granular separation of tasks. But ambition is a human trait and protocols progressively expanded towards use cases that were complex ganglia rather than ordered collections of atomic decisions: shall we embark into financing real-world credit or not, how active should our treasury management strategy be, how should we counteract the effect of our liquid staking services onto the stability of the native chain, what is our role in the complex DeFi stack, etc. The expansion created an issue of non-reducibility that engineers might not be able to fully grasp yet. It is structurally impossible to keep expanding while modelling every possible case for decision making purposes. We need to learn to coexist with innumerable edge cases that bear effects that cannot in any way be anticipated. The effect of non-reducibility can be disastrous.

Two possible solutions → The solutions available go in two directions: (i) make governance mechanisms more apt at dealing with unmeasurable uncertainty and conflicting interests, and (ii) reduce the uncertainty via the atomisation of tasks and responsibilities. Although the second (decompose, simplify, ossify) is what we should aim for in the long run, uncertainty cannot be fundamentally eliminated and therefore the development of a more uncertainty-proof decision framework is something we cannot run away from.

The rest of this post will be dedicated to an initial formalisation of the problem. When things get complicated I believe there’s value in developing a simplified version of reality. The idea is to use such framework to understand the key forces at play, and to try to design mechanisms that mitigate vicious effects while incentivising virtuous ones.

The Optimistic Governance Game

I decided to design games. Let me clarify: the Theory of Games and Economic Behaviour pioneered by John Von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, that made of mathematical rigour the basis of modern economics, has been abused and misused by crypto bros for too long and I have no intention to join the party. Those games won’t be game-theoretical, but gonzo-mathematical. Like gonzo journalism, the set of equations described below has been written with the intent to offer the vibe of what’s going on rather than to provide the symbolic tools required to distill a solution. Yet, formalising human interactions in the context of protocol governance is an ambitious task, and I hope this will spark the interests of others with more skills and time than myself.

I started by constructing an Optimistic Governance Game — or OGG. In the OGG all those participating to the governance of a protocol are good people, and intend to maximise the economic value produced by the protocol itself — important specification. In this simplified game configuration, we assume that participants/ voters receive one single proposal from outsiders, and have the ability to pass or ding it based on an arbitrary governance mechanism — i.e. a voting function.

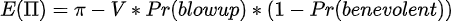

There are only two types of proposals: benevolent proposals and malevolent proposals. Benevolent proposals have a positive effect for all voters — and therefore the protocol, whereas malevolent proposals give an outsized benefit to the proponent (that resides outside of the voters set) at the expense of a non-negative probability of blowing-up for the protocol.

The expected cost of a blow-up depends on an assigned probability function and on the value V that each voter gives to the protocol. For simplicity we can assume that all benevolent proposals have the same payoff, and that all voters assign the same value to the protocol — and that such value is far higher than the potential value of a single passed proposal. With all voters having similar preferences, and being the proponents outside of the governance set, we can generalise the functions above from a protocol’s perspective.

Unsurprisingly, we can’t say in advance whether a proposal is benevolent or malevolent. We need to think in probabilities. We can rewrite the expected payoff functions of a generalised proposal as per the function below.

We know also that the vicious effects of a malevolent proposal will become evident only following an uncertain time delay — and only indirectly i.e. by observing the protocol’s survival. In other words, if by the end of the OGG — i.e. by time T, the protocol is still intact, our best guess is that no malevolent proposal has been passed by governance, and we won the OGG.

Concluding, the protocol, i.e. the sum of all the voters, when faced with voting in favour or against a generalised first proposal, intends to maximise the expected value function below. This objective is an assumption of the OGG, given that voters might be tasked in theory with very different objective functions.

Given the very simple structure of the OGG most results are trivial. Yet, they are worth reflecting upon:

There’s an incentive for proponents to go big → with the blow-up case being nuclear for the protocol, proponents are incentivised to bring to voters proposals that also offer high immediate benefits

There’s a dominant incentive to look good → higher (perceived) benevolence densities simplify decision making for voters

Illiquidity has a premium → late proposals, or better proposals with delayed outcomes, are more easily digestible by the decision making process

Maximising for value isn’t maximising for survival → a strategy of maximisation of the expected value might lead to very different optimal decision sets from one of maximisation of protocol survival

The Realistic Governance Game

Things get more interesting if we spice the game up a bit. Reality, and especially DAO reality, is way more complex than our OGG. For the sake of our discussion, I want to focus on few key differences:

Voters can also be proponents → There is a partial overlap between voters and proponents, of both benevolent and malevolent proposals — for this reason we will use the term participants, that includes both voters and proponents

Malevolent proposals are hugely beneficial for their proponents → The private (non-mutualised) benefits of malevolent proposals could dramatically surpass the private effects of a protocol blow-up for their proponents

Private and protocol perspectives differ → Private payoff functions of single voters/ proponents differ significantly from the protocol-wide payoff functions due to diversification and time horizon mismatches

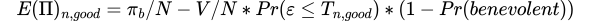

In the Realistic Governance Game — or RGG, we can rewrite the objective functions as follows — now distinguished between good and bad proponents. We assume there isn’t any cost in neither proposing nor voting.

Good participants → A virtuous proponent has an objective function that is widely similar to the generalised one of the OGG case.

As we have hinted to already, however, we have now itemised the expected payoff for each single participant n given that: (i) the time horizon of a single participant in the RGG might well differ from that of the protocol — i.e. a single participant might still sell his right to vote and leave, (ii) the damage for a single participant in the RGG might well not be nuclear given damage sharing and portfolio diversification. Those differences have the effect of increasing a good participant’s risk tolerance; participants have the incentive to “try their luck” with proposals that have a non-negligible chance of being nuclear for the protocol.

Bad participants → What happens for bad participants, however, is more interesting. A bad participant is one that consciously brings forward a malevolent proposal, enjoys the private benefit of such proposal, and consciously votes in favour of it.

The incentive to deviate for a bad actor is much higher: (i) only potential losses (and not extraordinary gains) will be mutualised, (ii) losses can be much more easily avoided given the better visibility of vicious outcomes. Bad participants have a huge incentive to bring malevolent proposals forward and to lobby good participants to minimise the perception of harsh protocol damage. Said differently, there is a huge incentive to deviate and turn bad participant, for everyone.

In this simplified representation the incentive to deviate is positively correlated to:

Expropriability → Relative size of private deviation benefits

Mutualisation → Community size, or total number of participants

Uncertainty → Perceived risk of encountering bad proposals

Urgency → Probability of the manifestation of malevolent effects

Risk aversion → Surprisingly, risk aversion incentives turning into a bad actor

Systems, however, aren’t immutable. That means that further malevolent actors will be attracted by large and uncertain communities, and their incentive is so high that they are ready to put significant resources to make their way through. This can create a death spiral for communities that do not have the right checks and balances.

What’s Next

Both the OGG and RGG are extremely simplified gonzo-mathematical games. They are nonetheless a good start, and can force us to look at the mirror and go beyond the personalisation of rhetorics when designing our coordination mechanisms.

Some protocols, including Maker, have remained loyal to the Tyranny of Structurelessness - h/t @Dermot_Oryordan, the defence of a purist approach where the formalisation of centres of interests (token holders, borrowers, $DAI holders, Core Unit members, delegates, minorities, the protocol) has been resisted in the interest of decentralisation. But, as Jo Freeman puts it in her monumental article:

“Contrary to what we would like to believe, there is no such thing as a structureless group. Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. […]

This means that to strive for a structureless group is as useful, and as deceptive, as to aim at an ‘objective’ new story, ‘value-free’ social science, or a ‘free’ economy. […] the idea becomes a smokescreen for the strong or the lucky to establish unquestioned hegemony over others.”

Whether this has been done intentionally or not is irrelevant. But using our simplified model, a homogeneous voter/ proponent body means increasing Uncertainty, Mutualisation, and potentially Expropriability. To me, Maker’s governance design is a bad design, as it incentivises adverse selection (among borrowers) and bad actor’s impunity.

There are, however, also good examples of governance in crypto. On June 10th, @skozin published on Lido’s forum a proposal to install a LDO+stETH dual governance mechanism for the liquid staking protocol. After recognising the existence of an agency problem where voters ($LDO holders) aren’t those suffering from disruption — primarily stakers, the proponents brought forward a set of ideas that are consistent with the framework we outlined above in the RGG:

Reduce the scope of governance via ossification → less Uncertainty

Delay execution of voted proposals → less Urgency

Introduce veto / counter-veto systems for $stETH → less Mutualisation

Implement (partial) burning of malevolent resources → less Expropriability

The proposal explicitly recognises the impossibility to identify ex ante all potential attack vectors or edge cases, and moves instead towards an informed-by-first-principles approach that, while acknowledging the existence of conflicting interests, stimulates an adversarial (and costly) governance debate. I would urge anyone involved in designing governance principles to go through the proposal thoroughly. It is one that would deserve a symbolic representation.

A dual governance system is not the only walkable route. Honourable mentions that would require much deeper analysis are Pocket Network’s stake-to-work mechanism, DXDdao’s reputation-based voting, reputation and participation decaying mechanisms, and obviously Ethereum’s EIP-5114 soulbounding. The research and design space of governance mechanisms for uncertainty-intensive environments is as vast and fascinating as it is relevant. We truly cannot build anything complex on top of a fragile base layer of human interactions.

Opting for the extremism of readily available solutions is good for politicians. But we are not politicians, we are here to stay and aren’t aiming to jump ship before the ship burns down. We have no option beyond keeping our heads down; studying, researching, testing, iterating, and dreaming big.