A lot of interesting stuff has been written about the blacklisting of Tornado Cash by OFAC and its implications on DeFi, crypto, financial markets, freedom of speech, and the history of mankind. On one side we have had decentralisation maxis hinting at the blacklisting of a piece of software as universal acid on its way to destroy the universe, while on the other hurried pragmatists were pointing fingers to the reality of things and the use of such technological tool to mainly do dodgy stuff, buy weed, finance terrorism, and promote chaos. You won’t get anything else on the matter from me. Extrapolating the motivations and implications of the event on the medium-to-long term future of financial intermediation and political freedom is twenty percent perspiration and eighty percent inspiration. We might as well indulge in guessing the effects of the recent FBI raid at Mar-a-Lago on the 2024 US presidential elections. Guessing is good to sell papers, and it’s not for me.

Currency Market Fit: Understanding Stablecoins

A currency is not very different from any other immaterial, man-designed, product. The magic that minted a physical, or at least measurable, object out of a whirlpool of beliefs and intentions is fascinating enough to deserve thousands of pages, but that isn’t the spirit of this piece. I am a currency junkie, as I admitted a few times here already, and I don’t intend to fall into yet another yes-just-one-last-time-I-know-when-to-stop-if-I-want epic of currencies as the ultimate philosophical achievement. But then I just did it, some might say. Anyway, a lot has been said lately about the opportunity or not of having one of the most prominent crypto currency projects out there, $DAI, pegged to its most powerful sibling the dollar, that I figured it would have made sense to put some order in the house and remind myself, and others, about the functionality of the pegging attribute. Rather than about magic, it should be about product market fit.

Elastic and Inelastic Money

Talking about a peg is talking about the elasticity of monetary purchasing power—price. But the elasticity of a currency against a foreign sibling—or a basket of siblings, isn’t the only way we can look at monetary price elasticity. Another one, to which we are better accustomed, is via inflation, or in other words the (evolution of) purchasing power against a basket of domestically-available goods and services. The two concepts are connected and both charged up with often unnecessary rhetorical drama.

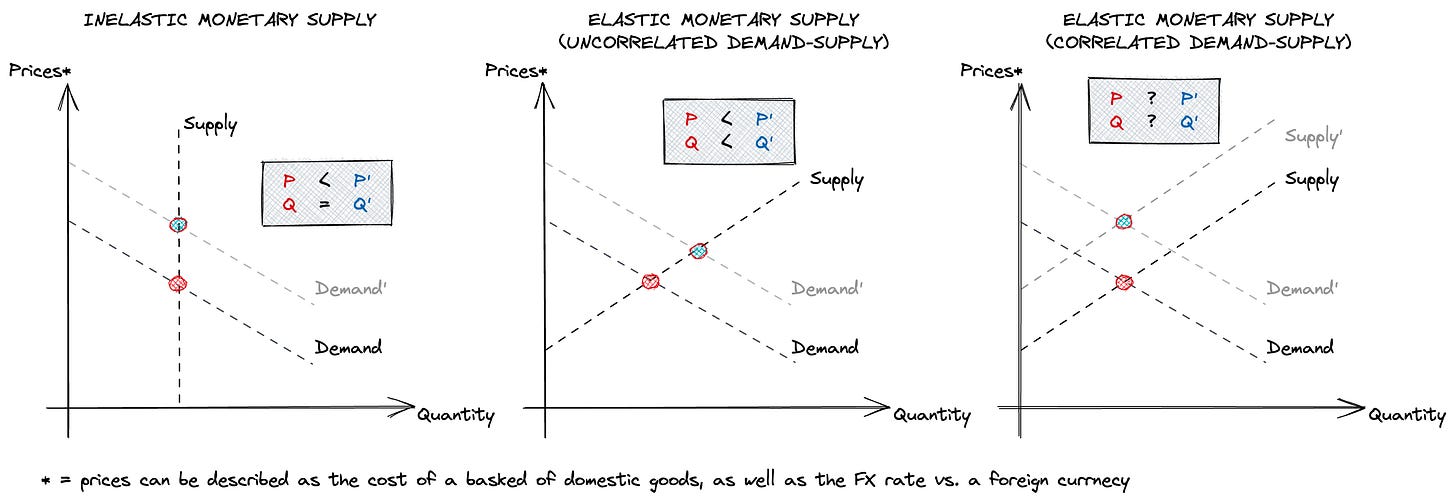

Money elasticity → We have encountered inelastic money, and more specifically inelastic US dollars, before—i.e. before the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. In neoclassical economics the interactions between providers and consumers of money can be represented through supply and demand curves like for any other tradable good. The (simplified) relationship between quantity demanded and (exogenously set) prices is well researched: all other things remaining equal, consumers would require less quantity of something if its price increases. The relationship between supply and prices is opposite: I am willing to offer even more of something if its price increases. For suppliers, however, there are more interesting second-order effects at play given that the ability to directly influence aggregate availability and market prices is real; we can however ignore those, assuming for a moment that there is one and only one supplier of money, and that the supplier has some sort of monopoly over it.

Inelastic monetary supply → The case of inelastic money is the easiest to grasp: the amount of money in circulation is fixed—or better doesn’t depend on prices and cannot be manipulated by the minter. There exists at any point in time an equilibrium in terms of purchasing power for each unit of currency. A shock in the demand function, driven by abrupt changes but also by standard economic expansion as well as evolving expectations, would translate in an increase or decrease of the purchasing power at equilibrium. Given the pro-cyclicality of human nature it is easy to see how those effects might become self-enforcing: e.g. expectations on future growth worsen → demand curves shift downward → equilibrium prices go down → incentives to produce goods diminish → expectations on slowing growth are fulfilled → and so on. The same can happen in the opposite direction. More importantly, the magnitude and consequences of those self-enforcing cycles are difficult to predict and make any economic activity linked to the quality of forecasting (e.g. credit) very difficult. Inelastic money is very bad in incentivising investments and protecting social stability.

Elastic monetary supply → Let’s introduce the ability for currency minters to expand the monetary supply—what Federal Reserve Notes did for the dollar. The ultimate effects on prices of changing demand conditions is now uncertain, given that the changes in the demand curve can be counterbalanced. We are at the early days of modern monetary theory. A regressive shift of the demand curve for money has been the main argument of post-2008 central bankers on why monetary easing measures have not been inflationary for the common citizen—although this cannot be said of their impact on investable assets.

An orderly market for money is of paramount importance for an economy that wants to shield citizens from speculative risks and provide economic agents with reasonably stable expectations to base their investment decisions on. The same reasoning can be applied when prices are measured not relatively to a basket of goods, but to another currency or basket of currencies. The effects of changing demand conditions are, in this case, even more easily assessable, thanks to the existence of a liquid foreign exchange market. The reasons behind active monetary manipulation, however, aren’t dissimilar: for economies that have a high relative exposure to (e.g.) dollar-denominated flows of goods and capital the stability of the local currency vs. the dollar is crucial. Foreign exchange stability in highly integrated economies facilitate foreign investment decisions and the purchasing of local goods—e.g. natural resources.

The monetary and economic interdependence between sovereign states and the United States of America has created huge governance and political distortion during the past century—I live most of the year in South America and I breathe a bit of that every day. Monetary connectivity, however, is more the effect than the origin of those concerns, since without economic, industrial (and military) independence it isn’t plausible to expect sovereignty of capital flows.

Elastic and Inelastic $DAI

The Tornado Cash drama turbocharged the debate around Maker’s relationships with the US dollar and its crypto proxies—mainly $USDC. It is renown how dollar crypto proxies represent today the vast majority (>80%) of Maker’s assets. Maker is in other words an extremely dollarised monetary system, and not everybody likes it.

But what does dollarisation mean exactly for Maker? In DR’s #40 we had defined $DAI as an anchored & algorithmic stablecoin. Parking the algorithmic component aside, we identified $DAI as anchored because its collateral pool (so far mainly $ETH and $wBTC) easily passes our exogeneity test. As a reminder, below is our test.

Defining what is exogenous and what is endogenous to a system is a tricky thing, as the boundaries of a system can get larger or narrower depending on the definition we adopt. $ETH, for example, is considered exogenous to the MakerDAO system in the chart above, but Maker is a project based on the Ethereum chain with currency printed through its technology; is $ETH truly exogenous then? I have a personal exogeneity test: is the project itself existential for the survival of such guarantee? If so, it is not an exogenous asset.

When we exclude dollar proxies, $ETH (and $wBTC) are Maker’s main guarantees to print $DAI. What should happen to $DAI following an increase in the dollar-denominated prices of this collateral? Given Maker’s design, and in alignment with neoclassical economics, we could expect a growth in the quantity of $DAI available, but with uncertain effects on $DAI prices relative to the dollar, as per the chart below.

With the amount of $DAI in circulation ranging within $5-10b, relative to $ETH’s $200-300b float, we can see how plausible it is for the upward pressure on $DAI to dominate—and even more so if we consider that straight $ETH is only 60-70% of $DAI’s non-stablecoin collateral pool. The picture doesn’t change during times of negative market sentiment: $DAI supply tends to reduce itself due to a decreasing demand for leverage while $DAI demand increases as traders chase less volatile assets to off-risk their portfolio. Both dynamics exercise upward pressure on $DAI relative prices.

Tectonic pressures → Are those effects immutable? Of course they are not, but the immaturity of crypto markets has provided way more upward pressure (relative to the dollar) on $DAI than downward one. If, on the one hand, this is testament of Maker’s solid design when it comes to over-collateralisation and collateral auctioning—downward pressure on $DAI would materialise if the market expected the value of the liabilities to exceed that of the assets, a volatile currency comes with a lot of strings attached. First of all, and probably most importantly, with the suppliers of $DAI being traders looking for leverage, it isn’t ideal for those traders that the currency they are borrowing in tends to significantly appreciate vs. the rest of their assets. Would you borrow in $CHF if you were living, for example, in Poland? I hope not.

Enter the PSM → The introduction of Maker’s Peg Stability Module (or PSM) was exactly functional to ease upward pressure on $DAI relative prices. By giving the ability to arbitrageurs to deposit whitelisted proxies of the dollar (e.g. $USDC) in a contract minting $DAI in exchange, on a fixed one-for-one ratio and no fees, the protocol granted itself the possibility to inflate its monetary base (vs. the dollar) in order to keep prices stable. The PSM proved to be a much better design choice than others, like Luna’s, for pegging. While the constructive pressures on Terra-dollars translated into the burning of the ecosystem’s equity token, $LUNA, de facto transferring value directly to equity holders—that could crystallise such value anytime at will, in the case of Maker pressures remain stored in the PSM. In all shapes and forms the size of the PSM is a measure of the excess $DAI demand at any point in time. The advantage of Maker’s design choice is that the same value can later be used to protect the price of $DAI if and when downward price pressure dominates. If you think of $DAI as a product to engage in the crypto economy for traders that base most of their investment framing in US dollars, the PSM has been a great introduction.

The costs of dollarisation → Nothing, however, comes for free. The deep interdependence between $DAI and $USDC has had costs for Maker:

Higher counterparty risk—vs. $USDC, especially considering that PSM mints $DAI without any over-collateralisation buffer

Less obvious differentiation as a decentralised product—vs. $USDC

Higher regulatory risk—vs. US regulators, considering that $USDC is a fractionalised and tokenised money market fund investing in US treasuries

Higher generic execution risk for Maker, without any impact on bottom line—Maker makes no money on PSM-minted $DAI

What most miss, however, is that $USDC’s domination of Maker’s collateral pool tells more about Maker’s inability to spin out new and better products rather than about an embedded superiority of $USDC as collateral asset.

Execution of a Revolution

We can assume for a second that it would be appropriate for Maker to reduce the dollarisation of its currency system. The assumption is non-trivial, but let’s put that aside for now. What would such de-dollarisation process look like? What would be the benefits of it, and what the threats?

Phase 1: Stop the dollarisation → c. $5.4b of dollar proxy exposure is not the maximum Maker allows, based on the current governance-approved parameters. Aggregate debt ceiling for those vaults amounts to c. $12.8b—makerburn, or almost exactly the double of what we have now. Of those, only the vaults related to Gelato Network provide a bit of yield (c. $630k/ year) while the others are there solely to sustain the peg. The first step of a de-dollarisation path should focus on drastically reducing available debt ceiling to stop the growth of those dollar reserves.

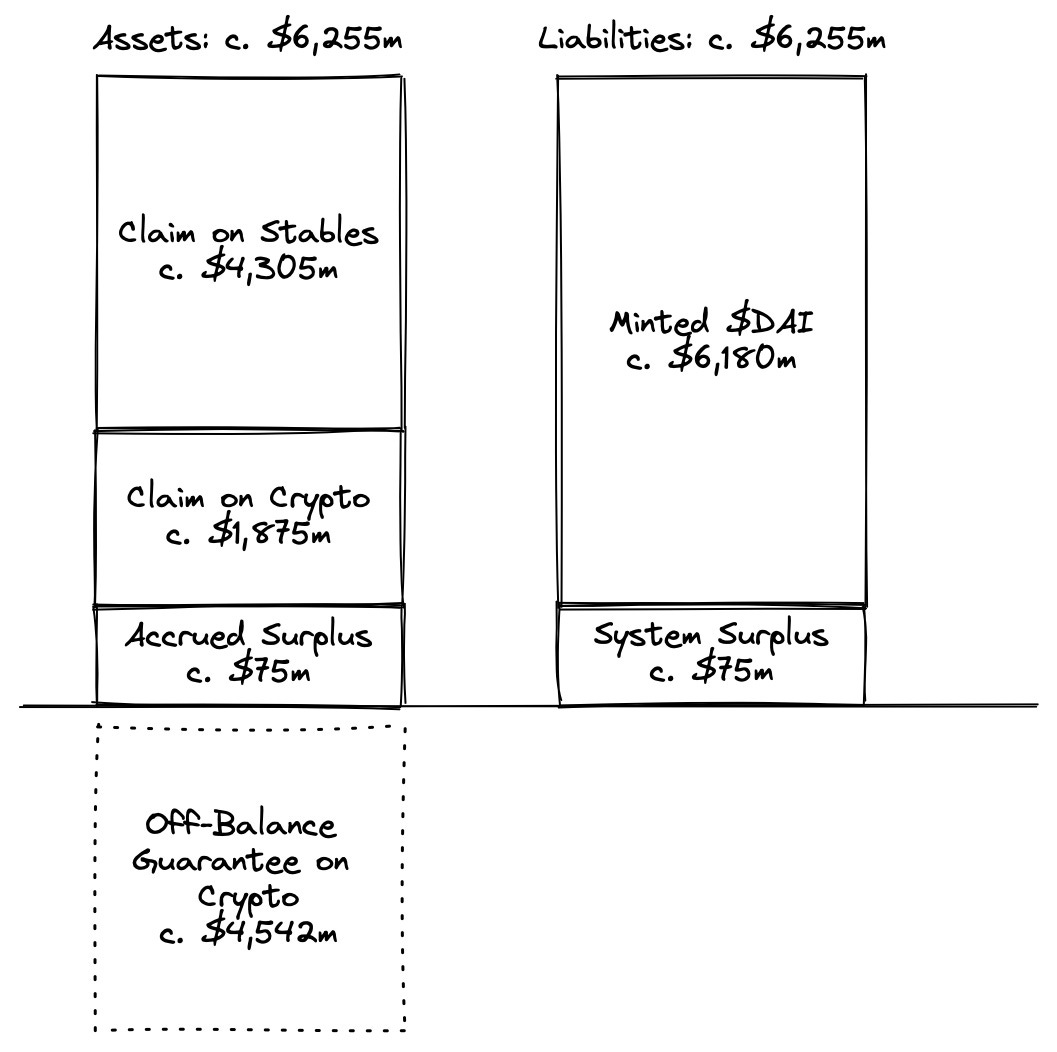

Phase 2: Incentivise $DAI supply expansion → As a reminder, $DAI is over-collateralised by a pool of crypto assets—below a diagram of Maker’s balance sheet from DR’s #40.

The inability of Maker to expand the stable part of its balance sheet further might put upward pressure on the value of $DAI that could be (at least partially) counterbalanced by new crypto-backed/ over-collateralised minted $DAI. In order to incentivise this, Maker could, alternatively:

Reduce the liquidation ratio or liquidation penalty for specific collateral types, thus increasing $DAI minting capacity—although the effects of this move are uncertain given the unpredictability of investors’ risk appetite

Reduce the stability fee for specific collateral types, thus making borrowing more attractive for seekers of leverage; this had been originally proposed by Mika and deployed on the stETH B pool by Maker—you can now mint $DAI against $stETH for no fees

Apply a negative DSR (Dai savings rate) on $DAI outstanding making it less attractive to hold $DAI—although theoretically doable it is extremely difficult to imagine how this could be applied in reality given Maker’s construct and the fact that it is not required for any user of the currency system to keep $DAI staked at the protocol level

Engage in open market operations by minting naked $DAI out of thin air and inflate money supply—there are several ways this could be mechanically done and each would require a detailed analysis

Phase 3: Dribble out existing dollars → PSM vaults (representing the vast majority of Maker’s proxy dollars) operate similarly to other vaults—albeit with no stability fee and a collateralisation ratio of 100%. Unlike regular vaults, however, users don't retain ownership of the asset and borrow $DAI, instead they swap the asset directly for $DAI, with MakerDAO owning the rights (and exposure) to the swapped asset. The cost for Maker of a (partial) devaluation of the underlying stable collateral could be devastating for the protocol—that in this case has no protection from over-collateralisation. Digesting (extremely) high levels of counterparty and market risks can be seen as the cost for the protocol to retain the excess $USDC liquidity. Again, there’s no free lunch. Although it might be prudent for the protocol to reduce the footprint of $USDC in the wider collateral pool, the unwinding comes with existential risk; while the protocol benefited from systemic liquidity by building up a treasury of billions of dollars, the decision to unleash the PSM in the first place might have been an irreversible one. No matter how you see it, the abrupt unwinding of all crypto dollars would come with huge execution risk and would have the de-pegging as the only plausible conclusion.

Below I listed three possible ways the $USDC legacy could be off-loaded. The description is non-technical, and the list is non-exhaustive.

Of the three methods, all with huge execution risk, it was #3 that was hinted at by Rune in Maker’s discord channels—although he U-turned immediately after in schizophrenic style. #3 is definitely the riskiest yet most exciting of the bunch. YOLO-ing $3.5b into an asset is truly DeFi-esque, and difficult to grasp for anyone who hasn't spent significant time in the sector. More than that, discussing it openly on forum before executing is mind-blowing for anyone who knows how modern central banking operates, or for anyone who was paying attention to the Luna crash. For posterity, I opted for stating my opinion at the time.

I am not a currency or macro trader and don’t want to make it too easy for those guys to figure out how to exploit a system that announces size and direction of its future trades right in the open. The master $UST-$BTC-$USD triangulated trade that killed the Terra project should still be vivid in our memories. The effects of the unwinding, however, even if orderly executed, are evident and should be discussed at length by community and investors. Unwinding (and limiting) present (and future) dollar exposure out of the Maker monetary system would mean a currency that floats freely against the dollar, most probably with a smaller currency base and, given the relative small size of $DAI float, with brutal volatility.

Is this a good market fit? It depends. I want to end by asking readers this and other questions, hoping that some of the $MKR whales would be among those readers too.

Q1. Does Maker have a shared direction of travel? And if so, what is it?

Q2. Is a de-pegged $DAI a good fit to achieve such direction of travel?

Q3. Is Maker’s current governance set up functional to achieve the common goal?

Q4. What are Maker’s competitive advantages vs. other projects—like $RAI or Aave?

Q5. Are Maker’s founders acting in the interest of most $DAI and $MKR holders?

That’s all folks, happy YOLO-ing everyone.