# 49 | What I Talk About When I Talk About Credible Neutrality

Smelly Coins, Gun Control, Monetary Middlewares, and Good Governance

Tradition tells us that the Roman emperor Titus Flavius Vespasianus, when confronted by his son on the disgusting nature of a big chunk of Rome’s taxation income, replied to the boy: money doesn’t smell. Vespiasianus’ Rome had just taxed, through the so-called centesima venalium, the public urine collected (and used for the production of ammonia) by leather merchants, and the political opposition was trying to leverage the origins of this conspicuous revenue stream. Legend wants that the emperor, having lifted a coin abandoned in deep shit in one of the prototypical public bathrooms that would have for ever taken his name—in modern Italian vespasiano is synonym of urinal, brought the metal to his nose and pronounced the fateful sentence: pecunia non olet. While many have extrapolated out of this event the eschatological story of money fungibility, my interest stays with the urinal, and with the political demonisation of a hole on the wall rather than of its very human misuse—being it during the deposit or the collection of excrements.

Op’ed for today. I hope I will be excused given the pivotal times. If you really don’t have the patience to go through the whole thing, please at least scroll to the very bottom and read What You Should Care About, it is dear to me and should be to you.

Two Distinct Regulatory Approaches to Infrastructure

It is not unusual for the political game to infuse with meaning a tool rather than its users. We tend to humanise everything in order to manufacture a connection and facilitate our behaviour within a system, and it is an ancestral phenomenon that makes for very powerful narrations. It works on the way up, with the worshipping of the human face representing a movement or a technology, and on the way down, with the demonisation of the same movement or technology due to the behaviour of such a face. More than that, the humanisation of technology (the term technology here is used in its original connotation of mechanical application of knowledge) artificially boosts the climb up and dramatically overcharges the absolutely human ego trips enhancing the destructive powers of the downfall.

Gun control → All this is common, yet dangerously mistaken. But if you think you are immune to this peasant-like behaviour, think again. To both the liberal Europeans and pragmatic Americans among the readers I whisper: think about your position regarding gun control legislation. It doesn’t matter whether you despise the dangers of a wide distribution of weapons across the common population or you welcome it in the spirit of territorial necessity: you are most probably infusing with human intention a piece of metal and plastic. The mathematicians among you might stretch to demonstrate that a widespread allocation of self-defence abilities could have positive implications on resource optimisation and on the survival of democracy, implications that way surpass the negative effects due to random violent misbehaviours. You could also substitute guns with memory state (read Ethereum) and get to a similar philosophical stalemate. Although guns (and infrastructural technologies) are just tools and should in principle be treated as such, ignoring or not (and to what degree) the human presence in the picture has several, and far reaching, implications.

The decision on how to (and by how much) regulate the interaction between technology and humans is ultimately a decision of social design. For my own applied research purposes, I have summarised the two main schools of thought as Technological Agnosticism—TA and Technological Pragmatism—TP.

TA distinguishes itself for the extremely liberal stance that technology should not be regulated per se, and that the regulator should give priority to the potential macro benefits of technological applications rather than to the micro tragedies deriving from their human misuse. TA tends to remain liberal ex ante, but strong in exercising its coercive powers ex post. It also tends to be extremely dramatic in its narration of the facts.

TP tries instead to predict the human interaction with the new abilities provided by technology, and to exercise its regulatory powers ex ante in order to minimise any possible negative spillover on single individuals. TP is high-touch, pragmatic rather than purist, coercive ex ante and lenient ex post—in TP abuses of a regulated matter can be at least partially imputable to flaws within the regulatory process.

It is far out of DR’s scope to argue in favour of one approach vs. the other. A preference can be backtracked to what the ideal role of the State as a collective contract should be when dealing with its citizens. Should the state be a protector of the rules of a game where the fittest prevails for the greater good of human advancement, or should it be acting with the powers and annoyances of a family father that knows better and exercises its authority on everything it can touch? It is not for me to say.

This is a publication focused on the technological and philosophical advancements brought by the DeFi movement, and how does all this connect with the current conditions of the sector we operate in? It obviously does. Following the most recent developments (on which a lot has been written) the two ideological camps have been forming again, with some switching sides. Humans are inherently pro-cyclical, reacting swiftly to the immediate and a bit less wisely to the long term impacts of their actions, and most recently even those that had been advocating for a low-touch approach to DeFi (and blockchain tech in general) are walking backwards on their footsteps. The damage observed and potential, they now say, is too deep.

Yes, I am a researcher/ advocate/ investor/ builder of decentralised infrastructure, and I would like to argue fiercely for leaving infrastructure alone and supervise closely the humans using it instead. But I won’t and will let others like @milesjennings do the heavy lifting for the industry. What concerns me here is ensuring that we approach the debate with a solid understanding of the problem space and unmask those individuals thriving in the grey zone.

The Importance of Credible Neutrality

We can’t debate whether technological infrastructure should fall or not within the grasp of the regulator without a working framework of what constitutes infrastructure. Ironically, I would argue that the most engaged among the activist libertarians aren’t moved by the good faith of protecting the infrastructure as much as by their ambition to keep the authorities away while they mind their own business. Once again we should tread carefully to avoid getting trapped in more dirty scandals. Laziness should never be a justification.

We tend to discount the acumen of the Legislator in dealing with novel technological phenomena, yet I find guidance coming from the SEC extremely useful in thinking what is infrastructure and how it should be regulated. From Miles’ Decentralization for Web3 Builders: Principles, Models, How—emphasis is mine:

To start, U.S. securities laws are generally intended to create a “level playing field” for securities transactions by limiting the ability of those with more information from taking advantage of others with less information. This is the principle of information asymmetry, and U.S. securities laws typically seek to eliminate asymmetry in certain securities transactions by applying disclosure requirements. The principle plays a role in the Howey test, the subjective test that determines whether U.S. securities laws should apply to a digital assets transaction where there is (1) an investment of money (2) in a common enterprise (3) with a reasonable expectation of profit (4) primarily based upon the managerial efforts of others. The fourth prong seeks to address information asymmetry on the basis of the belief that where there is a reliance on “managerial efforts”, the risk of information asymmetry (of the managers versus outsiders) is likely high, and therefore the application of securities laws may be necessary.

I am no lawyer, but even to the untrained eye it seems clear that the Legislator isn’t starting from a position of doctrine about what should be the extent of individual freedom, but rather from a desired outcome of fairness. The fact that retail investors typically benefit from the strictest forms of protection has to do with the recognition of retail’s inherent disadvantage when dealing with professionals, and not with some sort of ideological intention to control the masses, in my view. As Miles points out, it is (4) that remains more interesting in the context of web3 infrastructure. The author continues—emphasis is mine again:

Based on the above and SEC guidance, we can surmise that if a web3 system can (a) eliminate the potential for significant information asymmetries to arise and (b) eliminate reliance on essential managerial efforts of others to drive the success or failure of that enterprise, then the system may be “sufficiently decentralized” such that the application of U.S. securities laws to its digital assets shouldn’t be necessary. For purposes of this piece, I refer to these systems as being legally decentralized. Admittedly, the legal decentralization threshold will not be capable of being met by most businesses, but as I outline below, the novel components of web3 systems uniquely position them to meet such a threshold.

The question emerges then: are most endeavours that deal with (or facilitate) the use of crypto rails sufficiently independent from managerial efforts and control? CeFi, interestingly, has levered a narrative of facilitation for the common user to hide the truth of being simply a very centralised business that isn’t limited by any of the boundaries and protections that regulation has put in place over the years to avoid rug-pulling. But I won’t shoot on a dying corpse. However, while the answer for all so-called CeFi projects is a resounding no, I argue it is the same for most successful crypto-native DeFi projects as well.

A Short Story of Financial Innovation

My ongoing joke is that currencies are the most complex mass-adopted product there is. The set of mechanics behind the piece of paper we call dollar is deep, but all those complex interactions have been working smoothly (enough) for users to be ignored. A dollar, to most of us, is just a dollar and not a physical representation of future governmental liabilities whose maturity mismatching and distribution complexity are continuously managed by an intricate forest of qualified financial intermediaries. Ufff. Users just use the dollar, that’s it, and in exchange allow for the minters of these dollars to finance themselves at extremely attractive (and predictable) rates. Modern currencies, in other words, are phenomenal middlewares for value transfer.

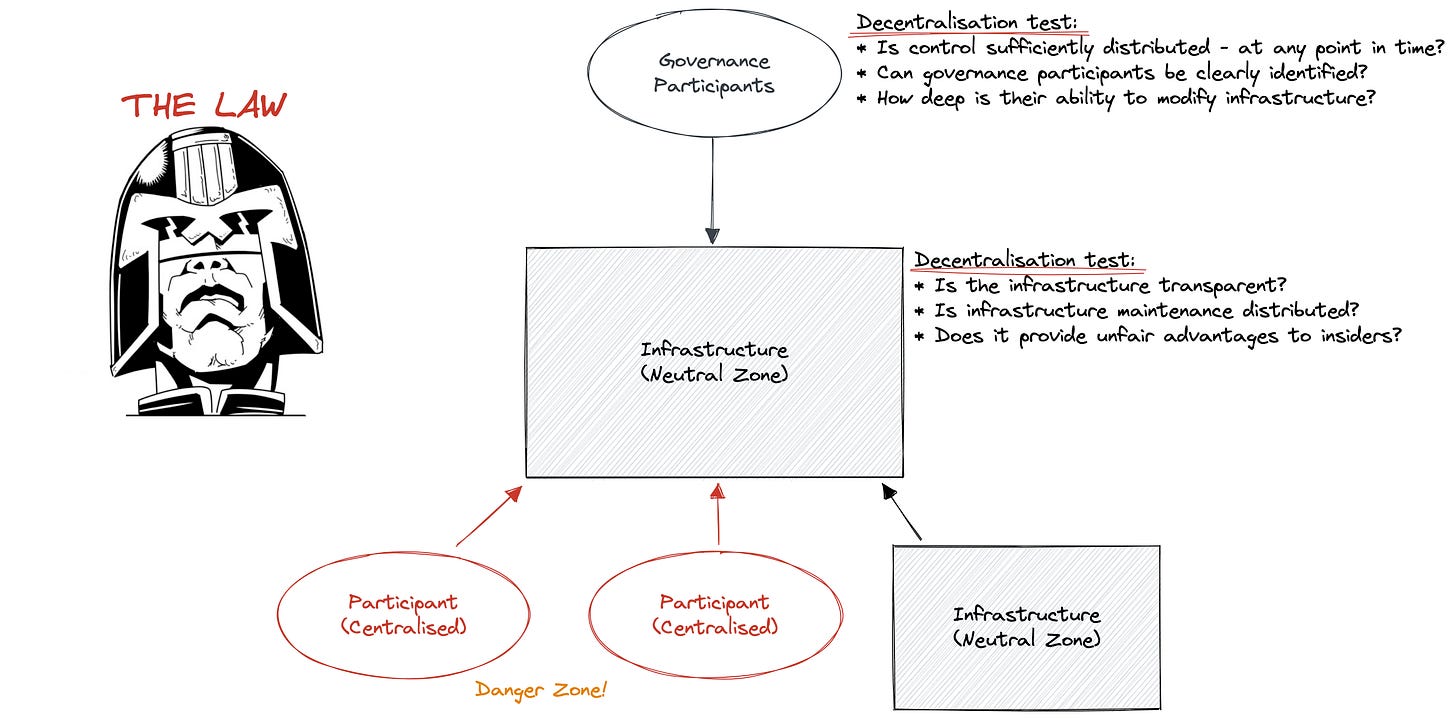

A monetary middleware could be philosophically decomposed as combination of three distinct layers: Governance—where decisions about what can come and interact with the middleware are taken, Purpose—representing the infrastructure through which value is managed, and Connectivity—constituting the front-end connecting users and infrastructure.

As always, macroeconomic factors have played a crucial role in directing innovation. So-called FinTech, for example, has focused over the last ten years mainly on the Connectivity layer—i.e. on trying to reach and package alternative forms of yield for a market starved for returns due to almost fifteen years of zero real yields. Not much has happened in the meanwhile at the infrastructural layer of wholesale banking, with a big part of the system still running on antiquated rails. Governance, however, has been the battle ground of two distinct armies: on the one hand the centralising forces trying to extend the reach of traditionally agnostic tools—read LTROs, TLTROs, and extraordinary monetary measures adopted by central banks, and on the other decentralising forces aiming at redesigning the balance of monetary power.

DeFi is just good infrastructure over a consensus layer → To me, while the political implications of blockchain technology and distributed systems are vast and groundbreaking, DeFi’s meaningful innovations have centred mainly around infrastructural advancements—and righty so: the ability to automate and open-source market making, derivative structuring, margin lending and collateral management, etc. DeFi’s successes and influence with regards to governance, instead, have been in my opinion massively overestimated—and impregnated with unsophisticated or bad faith ideology. Here at DR we have spent a lot of time discerning good <> bad infrastructure designs as well as good <> bad governance mechanisms, and I must say that the examples of virtuous governance have been very few. You can read here a primer on the growing pains of DeFi governance.

What constitutes good DeFi governance → My main conclusion (so far) is that well-designed governance mechanisms should:

Guarantee censorship-resistance (of the underlying consensus layer)

Incentivise virtuous (and minimise vicious) behaviours

Minimise (meaningful) human intervention (beyond maintenance)

Ossify infrastructures and isolate the human element

If we focus our attention on the protocols today providing crypto-native rails for lending, the picture is bleak—as usual we take Maker as exemplary case.

Censorship-resistance: Maker suffers from de facto centralisation of control in the hands of the founding team—see here for fun

Virtuous incentives: the combination of permissioning decisions (i.e. this collateral has the required characteristics to open a Vault at Maker) and financing decisions (i.e. the protocol will implicitly finance this collateral and socialise risk across $DAI holders) makes it very dangerous, when coupled with unsatisfactory censorship-resistance, to accept anything more complex than $ETH and $BTC

Human minimisation: although Maker is still heavily reliant on humans to develop (e.g. monitor risk parameters, onboard new collateral) and run (e.g. manage oracles and the liquidation engine) the protocol, human footprint is somehow sufficiently transparent for those interacting with the protocol to draw their own conclusions

Isolation of the human element: anyone with a brain can see where the protocol stops and who is taking fundamental decisions and driving risk-taking and managerial decisions

Dynamic standards → The minimum satisfactory threshold for any decentralisation test, as expressed in the chart above, should move depending on the activity the protocol is engaged in—or better towards which the protocol is directed by its governance actors. While very few could have argued that Maker was run as a centralised managerial company (based the SEC test) when it provided a transparent financing window to anyone who wanted to get leverage against their $ETH or $BTC, things now have become blurrier. With the protocol now accepting significant (for profit) counterparty and collateral risk (approved debt ceiling for centralised lending facilities is approaching $500m) at the expense of $DAI holders, can Maker still be considered a neutral infrastructure? I don’t think so. The protocol is currently driven by (heavily debatable) managerial decisions that shift returns and risks in different points, and provide preferential viewpoints to certain insiders vs. other participants. This means that $MKR could, in all form, be considered a security, and $DAI, assuming it would start floating at some point reflecting the inherent risk of Maker’s liability profile, should too.

Fascinatingly, the projects that have had less enduring success within the DeFi might be the only ones satisfying a decentralisation test. Liquity and Reflexer are good examples. There is nothing strange about it, when you stop and think. Infrastructure should be just infrastructure, the relevance of such an infrastructure should be attributed not only to its inherent characteristics, but mainly to the external conditions and the creativity of its users. There are no successful or unsuccessful bridges, there are badly designed bridges, well-designed bridges leading nowhere, well-designed bridges connecting two flourishing economies, badly designed bridges yet surviving in very strategic places, and so on.

What You Should Care About

If you got all the way here, kudos. If you skipped and went straight to the meat, well done as well. We are approaching David Foster Wallace levels of reflexivity in the debate, and things should be brought to a conclusion. So you can find below my Wittgenstein-esque guide to a well-formed debate about crypto’s regulatory implications. I printed it next to my screen. Maybe I should send it to Bankless for some higher quality podcasting—in case of interest.

A. Is the term infrastructure a relevant discriminant for your analysis?

B. Given A, do you have a well-formed definition of (neutral) infrastructure?

C. Given B, do you think the object of analysis satisfies it? If so, why?

The analyst will most probably realise that, assuming A and B, most protocols active in DeFi do not pass C. Very few protocols are decentralised under any well-formed definition. Decentralisation, for most crypto projects, is an illusion or a cover-up. But let’s assume C is satisfied and move on.

D. Given C, can you clearly distinguish participants interacting with the infrastructure?

E. Given D, can you identify the effective abilities of governance participants?

Now you are equipped with a working discriminant, a well-formed definition, and a satisfactory map. The debate is all yours. Do not trust those that transform a boring analytical process into an ideological campaign that is impossible to master, they are most probably hiding something. But if you want to follow a piece of advice, all that energy and passion could be better used in actually creating the appropriate infrastructural layers for the future of finance. That would also facilitate by extension the job of those actively working to protect the ecosystem against misinformed politicians and endangered incumbents.