I love cycling. I have a personal hero in the sport, and that hero is called Lance. Yes, that Lance. Lance the athletic machine, the obsessive perfectionist, the ruthless dominator, the man from nowhere, the cancer survivor, and the psychopath. I know where your mind is going right now: oh my god Lance the doped, I have seen him at Oprah he is a cheat, his EPO and testosterone and cortisone and the threats and the lies. Yes, that Lance. You are free to disagree with me on this, and you might well have great reasons to, but to me Lance is to cycling what Darth Vader is to the Star Wars saga: a forward-moving yet all-consuming force. I, like Lance, hold a picture of my chemotherapy-induced baldness handy as an antidote to the pettiness of everyday life, but that’s not why I love him. I love him because he is the necessary dark side of human development, an imperfect man sinking deep inside the darkness of his soul to allow everyone dream of higher plains. Lance was a bully, but a lot of great things got built on his life story—he himself ultimately paid the price for everything. In some ways Lance was the hero we needed, and the villain we deserved.

Others, though, I don’t respect. And that group includes the media who fed on his narrative and salivated on his demise, the UCI (read cycling regulator) that let it run for a decade while fully aware of what was going on, all the charities using his face to raise cash without asking themselves any question, the sports companies who built empires out of nowhere thanks to his achievements, and the wider public who was believing the BS about the Texan with the highest blood oxygen levels ever, and the BS about the fact that they themselves could also become gods on bikes if only they would swap light beer for EPO.

What does this have to do with Dirt Roads and financial markets? It kind of does.

Banking: the Great Unbundling

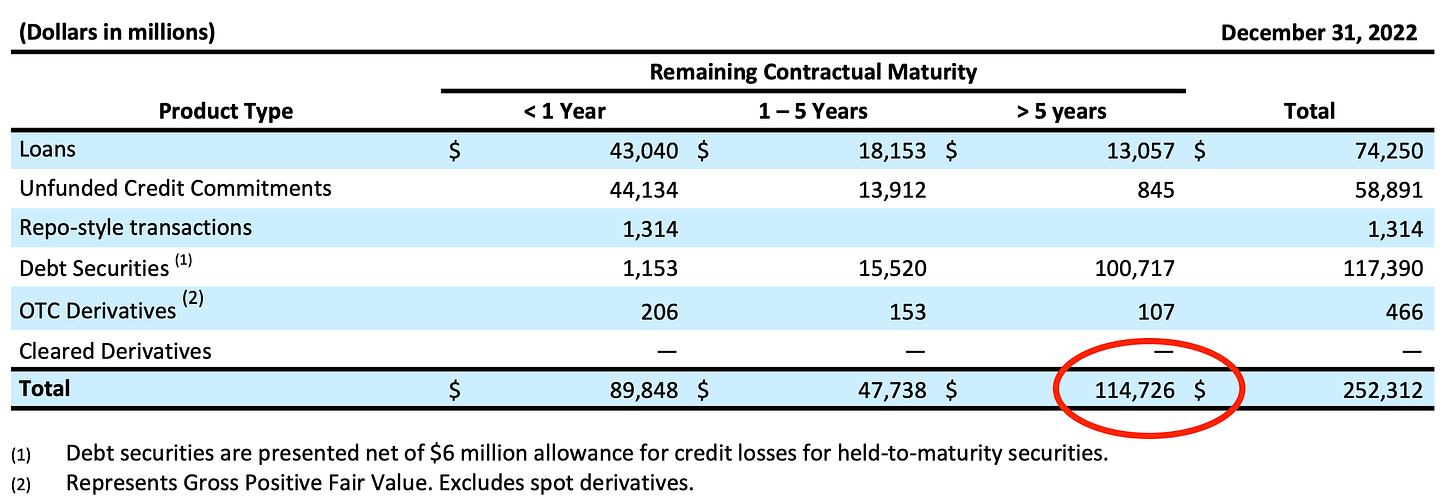

Silicon Valley Bank was no Lance—not anywhere as impressive on a performance standpoint, but it was loved and cheered until it was closed on Sunday by the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation, with all its depositors made whole by the FDIC. The fact that this was a shock for markets says a lot about the quality of markets. Below is an extract from Silicon Valley Bank 2022 regulatory disclosures.

Watchmen → I don’t want to bother you all with another watered-down description of the events of SVB’s last week, but I want to point to a fact: what was the regulator doing instead of observing the most classic of bank’s maturity mismatches? Is this a history of lack of professionalism solely on the side of the bank’s Asset Liability Committee? Geniuses can very quickly become villains, but who’s watching those watchers. As the Romans would say, quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

Incentives → I will push it all the way to conspiracy theory and stop one centimetre before is too late. Who was extracting the most value from SVB, or in other words who had more (short-term) incentives for SVB to keep operating as it was? Below is another interesting chart. Of the c. $250b lent out, almost half was in the form of governmental treasury paper—pretty much all long term. If there is one entity that benefited from very cheap long-term borrowing across the board, that was the State. The fact that the side of the state brain that borrows is not the same that sets the rates is a place I won’t go.

Returns → Finally, from the bank’s latest 10K, those securities were yielding c. 1.5%, making the average yield of total assets 2.73%—vs. 0.57% average liability costs or a net yield around 2%. Quickly looking at the market, the bank was printing 9-10% return on equity and a price to tangible book value of 0.85-0.90x—meaning that the market was thinking that SVB was pretty much at best compensating shareholders for the risk they were taking by buying the stock1. Matt Levine does a nice analysis of SVB’s basic financials here. Summarising: unable to grow the loan book as fast as their deposits the bank decided to go longer and longer on the term curve, and even that wasn’t enough to compensate shareholders. Sure, they could have also limited deposits grow, but they didn’t. The market saw it, the depositors saw it, and the regulators should have seen it too.

Spillovers → Among the depositors of SVB that had the risk of losing a big chunk of their savings was Circle, the minter of $USDC. Ironically, here on DR we had just debated about $USDC’s counterparty risk—this time nobody lost money so it feels good to remind myself of having written about relevant things before they happened. Below and extract from DR #52.

To me, it is not the story of mismanagement that matters, nor the finger-pointing. What matters is the blatant and absolutely unnecessary fragility of banking as we know it that emerged from this and other episodes. Today. we could do better.

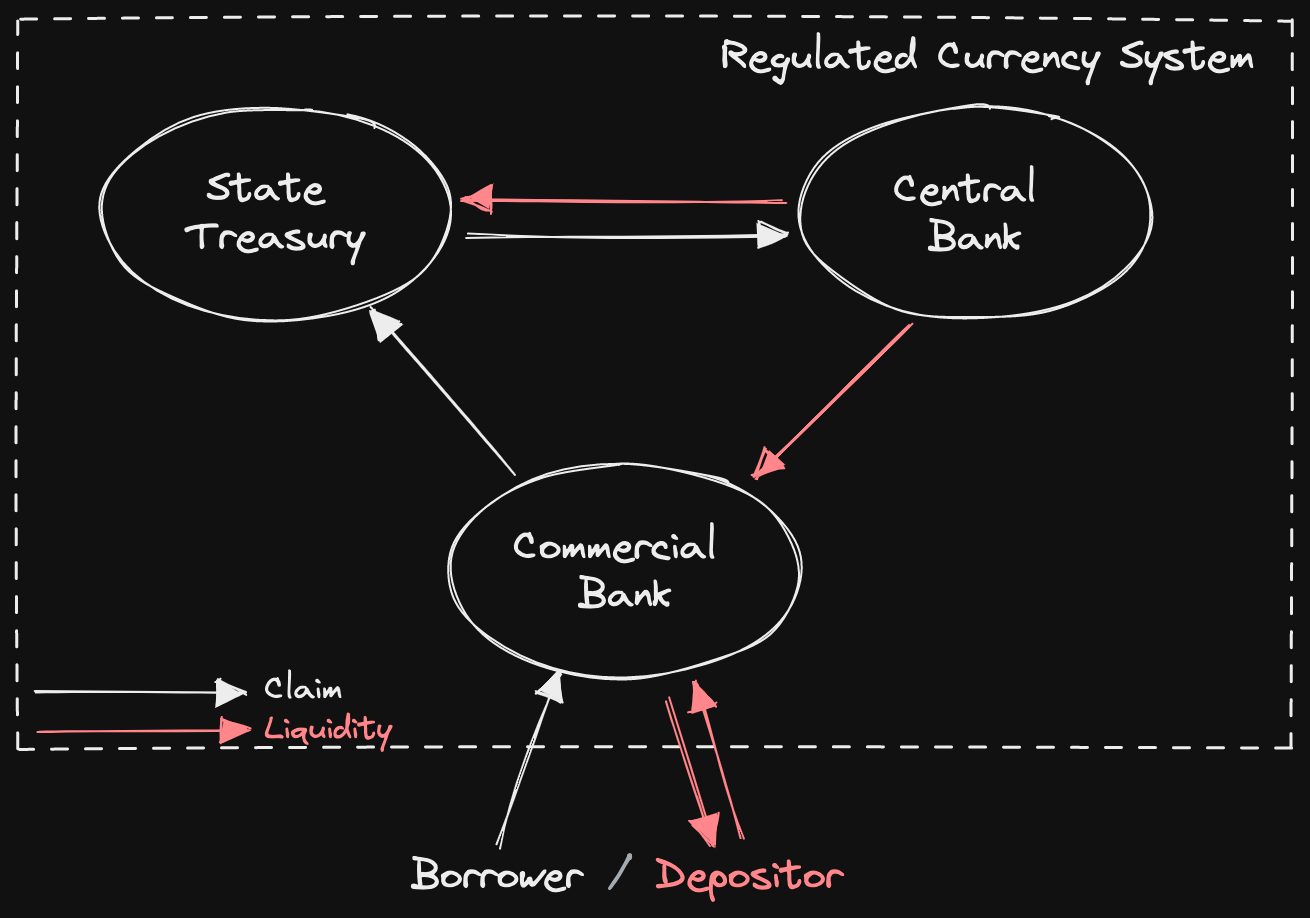

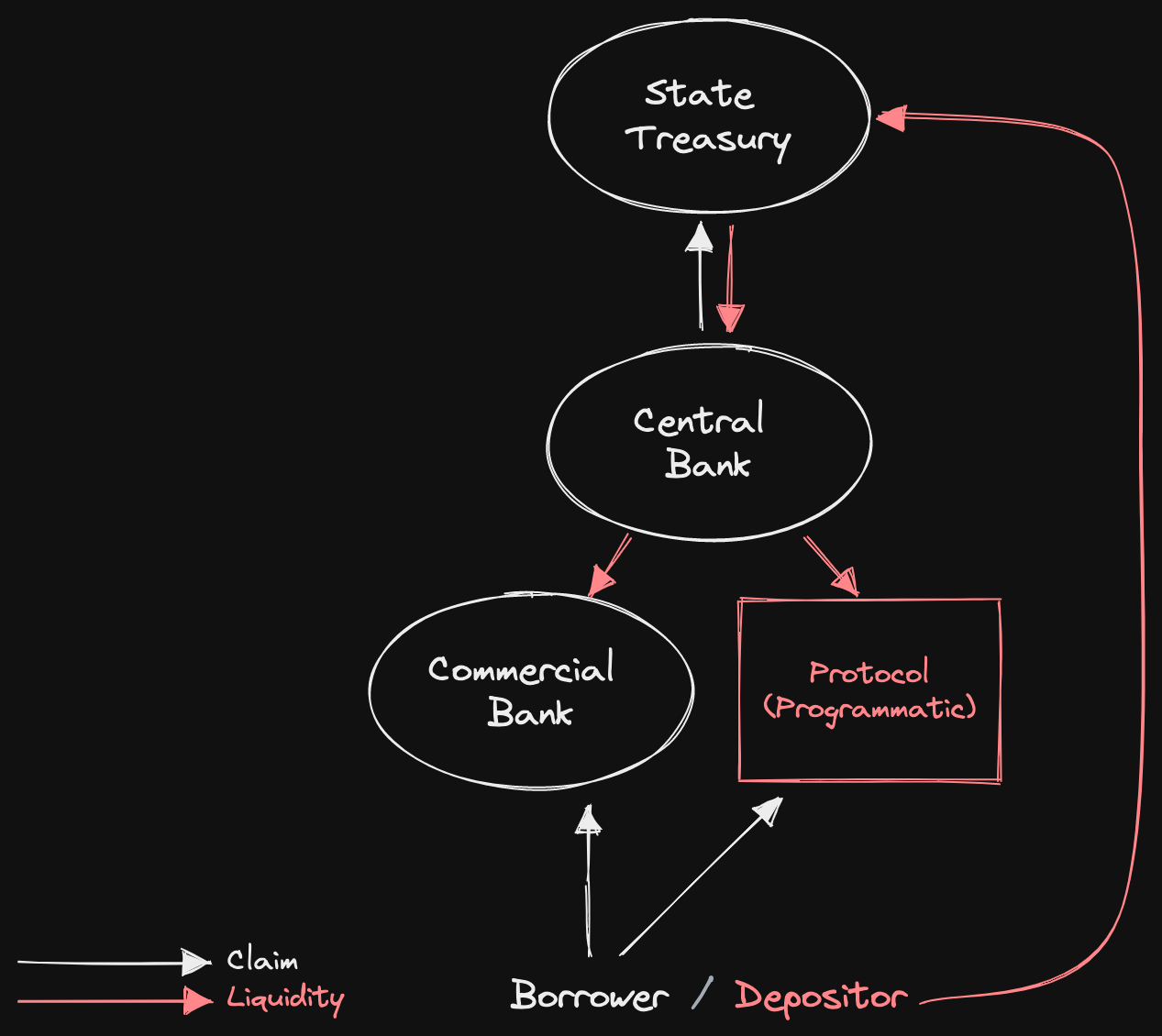

The «OLD» Monetary Triangle

The banking we know has been working relatively well, but it’s a fairly recent bundle. The system is based on a very tight and mutually beneficial relationship between (approved) commercial banks, central banks, and state treasuries.

Commercial banks underwrite liquidity needs and creditworthiness of the economy—i.e. borrowers, and provide loans in their own unbranded version of fiat money. Every commercial bank has its own version of fiat, they are NOT the same, but they are all freely exchangeable at par within a system that is permissioned by the Central Bank or other regulators.

Commercial banks maintain a monopoly on storage of such unbranded fiat—as well as dematerialised cash, by onboarding permissioned depositors—i.e. lenders. Those deposits get recycled by the same banks for other borrowers.

Central banks set and monitor compliance requirements (governance rules) for the participants to comply with, and in exchange guarantee fungibility of the various unbranded versions of fiat as well as provide emergency access to liquidity in case of mismatch.

State treasuries maintain some sort of preferential access to place their own (unsecured) borrowing requests—ultimately they set the rules of the whole currency system so they can do what they want.

Sure, this picture is highly stylised, but I hope is good enough. The system has worked very well so far because it has specialised each party in doing what they were good at:

Central banks could not underwrite the financing needs of all (retail and corporate) borrowers in the economy, and left this to commercial banks—which kept a spread to compensate for their services and capital at risk

Central banks could not maintain the storage of liquidity of their depositors, and could not interact with them to satisfy their needs on an ongoing basis

Commercial banks could not self-regulate because the risk of getting it wrong, given the highly levered nature of their business, would have been too high for the depositors—hence they provided the regulation part to central banks/ authorities which in exchange give them access to liquidity venues to absorb the whims of retail depositors

State treasuries need a ton of financing to look after operations, and need a big and reliable buyer—commercial banks provide this solution and for this reason holding state paper gets a very sweet treatment (e.g. 0% weighting in capital calculations)

With time, however, this system has started to show its limits across all dimensions.

Distribution → Do we really need commercial banks to distribute and maintain value storage in 2023? Probably not—read self-custody.

Underwriting → Are commercial banks equipped to effectively underwrite most financing requirements beyond the most standardised ones? Probably not—read shadow banking.

Returns → Can commercial banks be profitable enough given the macroeconomic conditions and the heavy regulatory costs put on them, also in the form of required equity buffers? Probably not—read risky balance sheets with super long durations.

Risk → Is the banks’ counterparty risk low enough for depositors to accept the fact that they get compensated with so little, and today even less than the risk-free rate? Probably not—read the attempts to connect liquidity providers to proper risk-free rates by so many fintechs and DeFi projects.

Banking is broken. But finally we can make a new (better) one with the pieces.

The «NEW» Monetary Triangle

I think there are no good reasons to keep the old bundle alive for too long, or at least no good reasons to defend it to death. DeFi gave us the intuition that you can actually split sources of leverage (underwriting) and parking places for liquidity. It was early days but the intuition remains. In a world where we can access in composable manners the best leverage engines and the safest deposit venues, the situation could look something like the one below.

In the new set-up, leverage venues aren’t the same venues used for depositing. That’s all good, but then where do liquidity venues get the liquidity they provide? Sure, some of that comes from monetary expansion (imagine Maker minting $DAI out of $ETH and $BTC rather than redistributing…$USDC) but that is not enough in quantity and stability. In my view, this missing link is the most natural place for a well-functioning CBDC: not a dystopian retail instrument that centralises underwriting and expands the control of the state, but rather a stabilisation instrument that central banks can use to stack underwriting and liquidity through the finance sector.

We now have the technology required to start thinking about diversifying sources of leverage—staked one on top of the other through code and rules, and we have the ability to let liquidity providers hold it being exposed mainly to the risk of the underlying minter (i.e. the state) rather than to the counterparty uncertainty of depository banks. As in every paradigmatic shift, there would be winners and losers, and it’s not surprising that those that feel losing control are fighting hard to discredit the intentions to innovate.

Commercial banks will see their activity drastically reduced, morphing into a utility and far away from the actively managed centre of investments they were. This is already happening. In a new construct, they could go back being a more efficient version of what they were, but this would require a cultural shift most incumbent are probably not ready for.

Depositors will see the counterparty risk they are exposed to massively reduced, in case they could access directly the printing machine. This could come, however, with high costs in terms of loss of privacy and control; designing the depositary stack will be as challenging as designing the financing one.

Treasuries will need to reorganise themselves to distribute their debt without causing dramatic shifts in their liability management.

All this definitely scares people—including me. During the most recent crypto bull run we had the illusion to be way ahead along this transformation process, and we all got burned. But this doesn’t mean issues aren’t real; the events of the most recent weeks are a reminder of that. My gut feeling is that the crisis we have seen emerging over and over at the commercial banking level could start climbing the ladder all the way up to sovereign treasuries if the monetary stack starts decentralising away from them. We have a currency system entirely based on a centralised (and militarised) borrower that controls the printing machine and the revenue distribution but that, even considering this, is basically broke. Exposing this crude reality to everyone is dangerous. Sometimes we want to illude ourselves that the volatility we cannot observe doesn’t actually exist. It is a fact of life.

Traditionally, the cost of equity of a bank is 10-12%. In other words, the market expects equity to return a 10-12% at least to compensate for the volatility of its earnings due to leverage and other factors. When the return of equity is lower than its cost (in normal conditions) this means that in order to compensate for this the price of the equity should be lower than its accounting (or book) value—i.e. its Price to Tangible Book Value multiple should be below 1. We talk about tangible book value because in the calculation of the book value of equity any goodwill (or other intangible assets) should be deducted as they do not constitute productive equity buffer for the bank to create yield on.

Amazing article, Luca. Loved it. Thanks for it. Reading your text I saw no mention to the fact of the current traditional financial system works with fractional reserves, and if I understood it correctly, your New monetary triangle (CBDC or CBDC+stablecoin system) suggests that we would have a system that would be full collateralized by Central Bank money. what are your thoughts on this? And again, thx for the text. I love it. And also as a Cyclist too the introduction was just perfect. ;)

Great piece, thanks Luca! I've been organizing my sporadic thoughts on how primitives in defi can make the banking system more stable and looking for thought experiments in this realm -- seems like I've finally found it.

In your new system, seems like depositors have no choice in choosing their counterparties (ie. the state treasury / central bank solely manage that). That's fair and suitable for retails since most don't want to bother with selecting counterparties when depositing. However, completely removing the market from influencing where capital flows and centralize that power to the central bank looks concerning to me. How are you thinking of making sure the most efficiently run banks stand out and get the liquidity they deserve?

I've been thinking through a model in which depositors deposit with commercial banks, having all deposit as mid to long-term but the receipts of deposit can be used as money -- making it even the long-term deposits convenient to use for commercial activities. In this scenario, banks put up a certain percentage of capital as collateral to "lever up" (ie. taking deposits). The revenue of the lever up is split between bank and their depositors by a certain ratio, similar to the GP/LP incentives structure in VC/PE, and with the bank's collateral as a buffer if anything goes south.

Would love to hear your thoughts. In general, I like how defi CDP can "make any relatively liquid assets / claims function like cash" and think this primitive shift can go very far in shaping the new financial system