Last week I had the pleasure of attending the Point Zero Forum in Zurich, invited by my old friends at Oliver Wyman, as one of the (many) speakers. For lack of a better description, the Forum is an attempt by Elevandi and the Swiss State Secretariat for International Finance to gather Who is Who across financial regulators and businesses and make some sense of what is going on in financial innovation. By its own design, the Forum is a messy one, as stakeholders have massively diverging perspectives, incentives, and agendas. This is not a problem of Point Zero specifically, but of conferences more in general, where the public set-up incentivises attention-grabbing, self-promotional conversations, and ultimately intellectual adverse selection. Those having more to give than receive, or busy building serious stuff, tend to stay away, on average. We should probably rethink the way conferences work and, as usual, it seems we have already been there.

Breaking Point (Zero) (Apart)

The Royal Institute of International Affairs (aka Chatham House) created in 1927, and later refined, a socially-enforced ethical rule allowing to reference the content of a debate, yet without mentioning the participants and their affiliation. The intention behind such a rule, dubbed unsurprisingly simply the Chatham House Rule, was incentivising an open and useful exchange. I attended several debates held under the Rule, continuously amazed by the fact that something without any legal or regulatory enforceability could be so effective. To me, the existence of the Rule has been a healthy reminder that everything symbolical, including states or constitutions or money, is a social construct—and not necessarily official constructs are stronger than unofficial ones.

But back to Point Zero. The reason for me attending the conference was exactly the invitation to participate to one of those debates, a behind-closed-door roundtable about the future of money—held in compliance with the Rule. Once more, I can attest of its efficacy in stimulating great conversation.

The fifteen-ish participants included (remember I can’t disclose exactly their names or affiliation) central banks, traditional large and renown commercial banks, blockchain-friendly financial institutions, blockchain-focused infrastructural and financial companies, consulting firms, and myself—I guess as CEO of M^ZERO Labs, researcher, of simply opinionated figure. The fact that very few people understood (and understand) what we do at M^ZERO Labs made the conversation, and the invite, even more stimulating. I left the room, following the ninety minute long debate, with further clarity about today’s monetary battlefield—yes, battlefield. Energised, concerned, and drastically more aware of its prominent actors and agendas.

Point Zero, held in June 2023—somewhere in the cyclical middle point between the boom and the bust, was in my opinion a very relevant event, and therefore I want to share with my readers, here below, which are My Ten Takeaways. I hope those will inform builders, participants, zealots, and critics, beyond the too many memes and generalisations. All in compliance with the Rule, obviously.

My Ten Takeaways from Point Zero 2023

#1 → Product and value are irreconcilable viewpoints. Point Zero reminded me of the irreconcilable dichotomy that currently exists in fin-tech, where let’s call it 50% of the audience comes from finance (read value intermediation) and 50% from tech—or often product management. The reason is historical, with the first fintech wave (2000-2020) being entirely concentrated on creating sleek frontends running on antiquated tech stacks, obsession was product and not infrastructure. The problem, here, is that tech people truly struggle understanding that when we talk about money, we actually talk about value intermediation rather than payment solutions. Money, against common wisdom, wasn’t born as a form of more convenient barter but rather as a synthetic form of debt. Today finance (which is philosophy and mathematics) continues to think of value intermediation—or monetary expansion, while tech keeps hearing payments. There is no right or wrong, but those viewpoints are fundamentally irreconcilable. Interestingly, the same lack of mutual understanding does not exist among those active in the second wave of fintech—let’s call it DeFi, where protocols have been focusing entirely on improving the infrastructure of value transmission and the creation of incentives rather than spinning out payment solutions or front-ends.

#2 → It is all about controlling the money printing machine. Here on DR we have discussed extensively the so-called monetary triangle—which includes state treasuries, central banks, and commercial ones. See #53. The «old» monetary triangle has worked relatively well in the past, but its limits are becoming evident:

The underwriting function of commercial banks has been challenged for a long while, with capital markets (or shadow banks) progressively stepping in. See below an extract from the Bank of England’s latest Financial Stability Report:

MBF (Market-Based Financing) is the system of markets, NBFIs and infrastructure, which, alongside banks, provides financial services to support the wider UK and global economies. Such services include providing credit, intermediating between saving and investment, insuring against and transferring risk, and offering payment and settlement services. Between the start of the global financial crisis and end-2020, the non-bank financial system more than doubled in size, compared to banking sector growth of around 60%. As a result of this growth, non-banks now account for around half of the total assets making up the global financial system.

The distribution function of commercial banks, as well, has been progressively bypassed by technology, making less digestible to the users the excruciating counterparty risk they need to digest simply to digitally store and use their assets

During the pronounced liquidity cycles experienced in 2007-2011 and 2020-2022, central banks and governments (indirectly) had to stretch themselves in providing risk capital to the economy—also here, exacerbating further a) the importance of controlling the printing machine, and b) the narrowing scope of traditional commercial banking

In the ongoing reshuffling process of the monetary triangle, everyone is trying to keep their hands on the printing press. Those who do will be able to control the amount and rates they are financing themselves at, while keeping the luxury of time in resolving inflationary or deflationary messes when they happen.

#3 → There’s private money and private money. What follows from #2, is that governments get quite nervous when innovators bring forward private money ideas. Truth is, however, that we are already swimming in private money— by the end of 2022 the ratio of overnight deposits vs. currency in circulation in the ECB area was 6.4-to-1. What the regulator seems to like of bank-printed private money is control: they can control the ultimately supply of it through various types of reference rates, and they know who they need to investigate when things go bad. Regulators don’t like this thing crypto-nerds call decentralisation. For this reason, any type of private money that is fully digital and decoupled from the sovereign system, like those backed by $BTC or $ETH or their derivatives, will have a very very hard life to exist on regulated financial rails. It might not mean anything for reserve assets (that aren’t money) but it might make the hell of a difference when it comes to value transmission. In my opinion private money preachers (like myself) should try to pitch to authorities that there are newer, and better, systems to control money transmission and improve transparency.

#4 → Expecting traditional banking to facilitate monetary innovation is foolish. Continuing on our argument #2, it would be extremely naive to believe that (most) traditional banks would support proper monetary innovation. Efforts in e-money, or even tokenised money—like Circle’s $USDC, have been cornered to payment and settlement use cases that are completely dependent on banking rails. Those innovations, from a monetary perspective, are almost irrelevant, while actually (this is only a personal opinion at this stage) running the risk of further exacerbating centralisation in large liquidity custodians and the fragility of the system as a whole. Although the opacity of the universal banking system, as well as the inefficiency of a model based on large core capital buffers and regular bailouts, have been evident for a long time, banks will still play the card of “you know who to talk to (or fine) if you need” with regulators—and keep lobbying accordingly. This type of defence will most likely be stronger in developed sovereign monetary systems (like the US or the Euro area) that have worked reasonably well and are net capital importers.

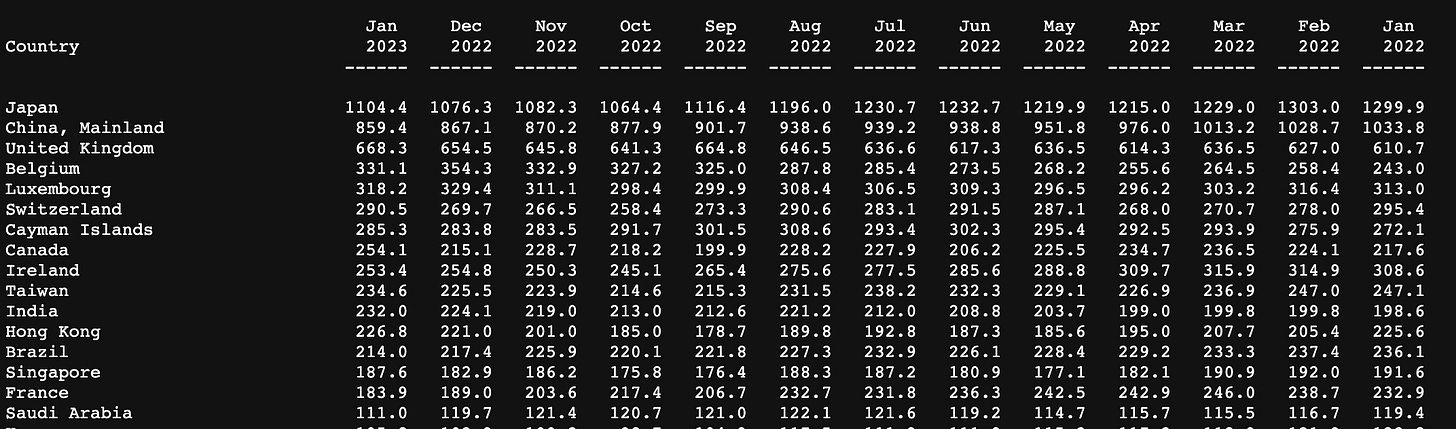

#5 → Monetary innovation will start as an offshore phenomenon. What follows from #4, is that monetary innovation will most probably kick-off outside of the dominant sovereign monetary systems. As we know, the dollar is not only in use within the US economic system, and today numerous other economic systems (often extremely large) continue to reserving, transacting, and denominating their activity in $USD. Interestingly, and not coincidentally, many among the largest foreign holders of US Treasury securities are the same net capital exporters potentially interested in participating to novel synthetic dollar creation. The Eurodollar market—i.e. the market of dollar-issued instruments floating outside of the US dollar currency system, seems the ideal turf for (dollar-denominated) monetary innovation.

#6 → Commercial banks are the weak link, and they know it. Arguably, further global dollarisation would end up being a good thing for the owner of the dollar printing machine, and as a consequence for the ultimate dollar borrower—the US Treasury. Digital dollarisation could be, in other words, new life in the battle to remain a global reserve currency. This thesis assumes that the creation of further synthetic dollars (in large amounts) will be in compliance with good practices and without breaking the link with the US-denominated debt instruments par excellence, as we have discussed in #3. In other words, a US treasuries-backed tokenised Eurodollar could ultimately be very good for the US Treasury itself—while not being excessively harmful in breaking the existing monetary policy levers.

It would be however terrible for commercial banks. The fact that today’s technological stack can allow the creation, monitoring, issuance, and composability of such a tokenised instrument without the intermediation of regulated commercial banks engaged in distribution, makes those commercial banks the weak link of a new hypothetical monetary triangle. Independently from the way you see it, technological innovation is eroding the economics and plausibility of the universal banking model. Attacking their remaining protected area, i.e. dollar distribution and storage, would be a fatal blow. True, narrow banking can be a profitable business as well, but will require a paradigmatic shift on the way those businesses operate.

#7 → Capital markets already provide solid infrastructural grounds. The original sin of most DeFi<>TradFi bridging projects has been to ignore the extremely sophisticated infrastructure already existing in capital markets, and pretending that what is required off-chain to port value is a simple and bureaucratic piece of the puzzle. It is not. The obsession about the meme of tokenising real-world assets is a product of this misconception—and probably also of the fact that too many product rather than finance people have been involved in the process as per takeaway #1. 2023 wasn’t a record year for US mortgage-backed securities issuances in the US (-58% YoY) but still that market alone has seen c. $500b of market issuance. There is not a single underlying mortgage that has been tokenised or digitised—those mortgages are packaged, analysed, rated, custodied, and serviced, while synthetic securities that depend on them are issued. Rather than tokenising real-world assets, we should talk about permissioning access to liquidity, with buckets of value that back their digital representations managed by approved actors based on certain guidelines. The lucky reality is that capital markets already offer the required (off-chain) infrastructure to do this, battle-tested by decades and tens of trillions of issuance. RWA tokenisers should spend more time looking at how CLOs work.

#8 → It’s not only the message, it’s the messengers. The content of the message is not enough to convince an audience, or to enact change. It is also about the quality of those working on the problem set, about their abilities, and their intentions. It is fair to say that the DeFi movement hasn’t been represented, in the recent past and most probably in the present, by the very best interlocutors. We should all be aware that this constitutes an existential risk for the industry. High-quality, long-term oriented building should be incentivised, against the worshipping of incredible and immediate profits. If FTX had devastating effects for the industry, even considering that we were observing the default of an unregulated high-leverage exchange (a business model closer to gamified retail brokering or spread betting than $BTC) rather than a money transmission innovator, we can only imagine what the blowup of Tether might do.

#9 → We must remember we have already been there. As usual, I am reminded of the mantra to never take ourselves too seriously. Technological shifts have happened in the past, showing similar patterns of exuberance, speculation, attack by incumbents, adoption, and commoditisation. We should learn from the past. We have been here with the printing press, the internet, Bretton Woods, and crypto. Below, one of my favourite extracts from one my favourite books—The Structure of Scientific Revolutions:

Max Planck, surveying his own career in his Scientific Autobiography, sadly remarked that “a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

#10 → It will take courage. And a lot of it. But that’s the fun part.