# 64 | PREDICTION MARKETS (II): Spoiling the Election Love Story

Not So Fast, Elon. An Op-Ed For the Last Pre-Election Weekend

Special thanks to Omer Goldberg, founder and CEO of Chaos Labs, whose insights made this piece possible. Not only for providing the data but, more importantly, for the invaluable philosophical conversations on oracle design and the nature of information by the East River.

The recent spike in interest around prediction markets, especially as they become a go-to resource for forecasting the outcome of the 2024 US presidential election, has pushed this theoretical primitive into the spotlight. Fuelled by both my own fascination and this surge in market relevance, I dedicated the latest edition of DR (#63) to establishing a theoretical foundation for the prediction market phenomenon. While abstract, I knew this piece would have ignited the right conversations with the right people—and I wasn’t mistaken. Things got even hotter during the last weeks, and a pre-election, data-driven, Chapter II was urgently needed.

Prices as Probability Predictors

My journey as researcher and builder has been marked by a long-standing fascination with prediction markets. Their unique potential to enhance the accuracy of information—both about the likelihood of future events (predictive insights) and the verification of past events (oracle functions)—places quantifiable prediction markets among the most intriguing innovations in blockchain-enabled technology.

Smart contracts, with their capacity to autonomously initiate sequences of actions based on predefined inputs, depend heavily on the external information provided by so-called oracles. Prediction markets, with their arguable ability to refine a system’s predictive accuracy, offer a promising avenue to elevate oracle reliability, particularly within specific, well-defined contexts. This intersection of prediction markets and oracle quality represents a frontier with the power to reshape our understanding of decentralised, trust-based information systems.

Why do people care about prediction markets? Well-functioning prediction markets carry profound philosophical implications that captivate builders and theorists alike, particularly due to their potential to:

Embed intangible insights, translating otherwise elusive guesses into actionable insights, and enabling systematic decision-making across contexts where traditional measures fall short

Expand uncertainty-driven financial instruments by incorporating novel sources of uncertainty into measurable risk frameworks. Prediction markets can foster the development of event-driven risk instruments, opening pathways for innovations in areas like insurance contracts and risk intermediation

Enhance predictive accuracy for bias-prone events, theoretically improving forecasting accuracy for certain events that are susceptible to reporting biases when approached through conventional predictive methods, offering a more decentralised, evidence-driven alternative to standard polling techniques

The last point is especially relevant in the context of election contests, where betting markets are often banned and news coverage and polling can be tainted by hidden political agendas. In prediction markets the financial stakes should drive participants to pursue accurate predictions over partisan narratives, creating an information ecosystem where incentives are aligned towards truth-seeking.

Prediction markets surged again into the public eye during the 2024 US election campaign, with platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi reporting billions in betting volumes. High-profile figures, including Musk, amplified this trend by sharing market odds on social media, and treating them as more reliable guesses of the common wisdom. Yet, while prediction markets gain traction as a new tool to gauge sentiment, questions about accuracy, market manipulation, and reliability of those platforms emerge. The potential of those tools remain undeniable, but assessment circa their reliability might have exaggerated their maturity state.

Good Markets, Bad Markets, and Polymarket

Polymarket’s capacity to attract speculators interested in the US election outcome (thanks also to some regulatory arbitrage) has quickly positioned the platform as an ubiquitous reference point for both political analysts and everyday people. But is Polymarket currently a well-formed prediction market? And more in general, what makes a prediction market a well-formed market?

Academia suggests that for prediction markets to serve as unbiased predictors, certain conditions must be met:

Diverse risk aversion. When participants vary in risk tolerance, markets are more stable and prices better reflect true probabilities. Overly risk-seeking or insular communities tend to produce biased predictions, as shown in studies by Wolfers and Zitzewitz—2004

Liquidity and market depth. Higher liquidity smooths price fluctuations and ensures that prices adjust quickly to new information, making them closer proxies for event probabilities. Gjerstad (2005) and Oprea, Friedman, and Anderson (2009) demonstrate that deep markets improve the reliability of price signals

Wealth distribution. Equitable wealth distribution among participants prevents large players from skewing prices. Concentrated wealth can distort predictions, as noted in studies by Manski (2006) and Tetlock (2008)

Do leading prediction markets show traits of a well-functioning market? Unfortunately, recent data suggest otherwise.

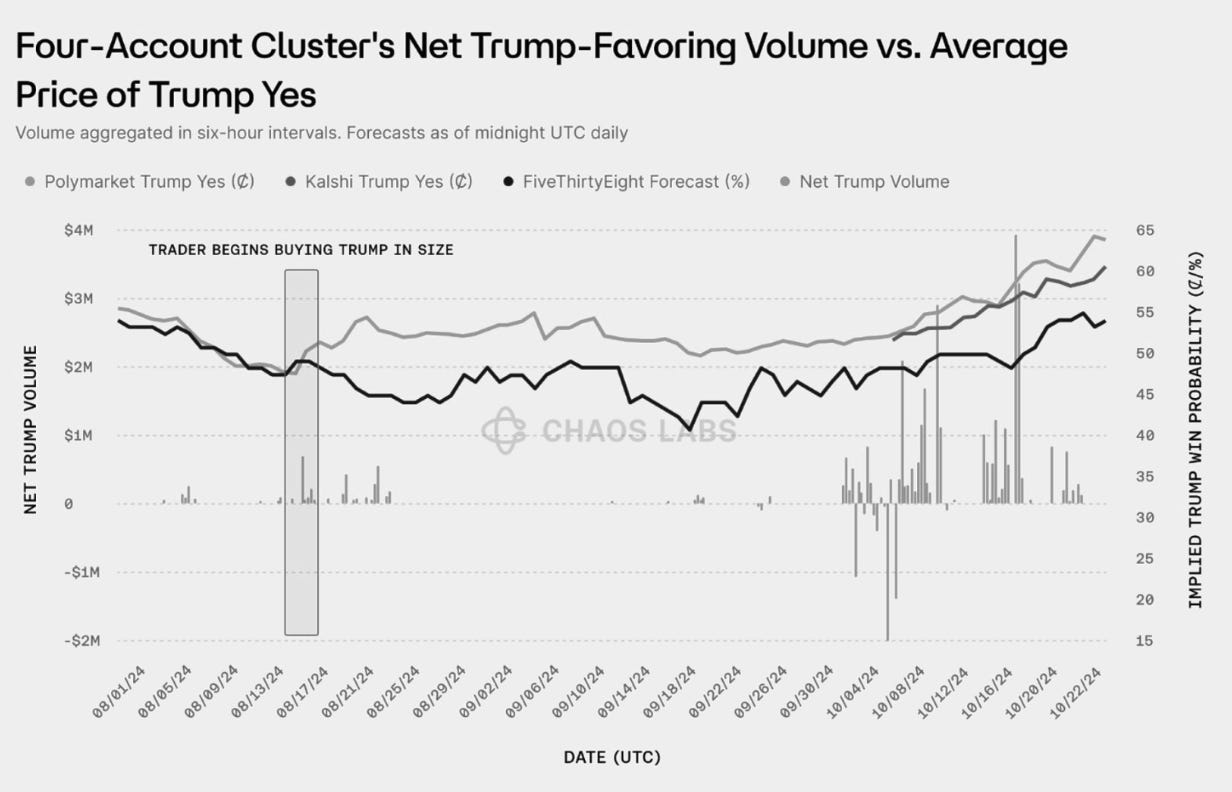

On October 24, Omer analysed Polymarket’s trading dynamics on several key days, documenting his findings in an X thread. Based on recent on-chain data, Polymarket’s 1-cent depth (the order size needed to shift the price by a cent) stands around $100k, leaving it vulnerable to shifts by a single motivated trader or coordinated group. The events around August 17 reinforced the concerns for Polymarket’s lack of liquidity and excessive trader concentration.

August 17th: a Case of Market Distortion

On August 17, a proven cluster of four trading accounts (Fredi9999, Theo4, PrincessCaro, Michie) began a significant accumulation of Trump Yes shares. Across these accounts, the trader purchased a net $717k in Trump Yes shares, which constituted 28.3% of the day’s total market volume. Polymarket later confirmed this event in a New York Times article. Further investigation showed this cluster represented at least 20% of daily volume on seven other days, with the most concentrated trading in August, which was the period when Polymarket’s Trump odds started to diverge sharply from polling consensus.

The Poly whale → Today, the same cluster of accounts controls roughly 23% (!) of the market’s open interest. The impact of a large, concentrated trader on market prices is substantial. When one entity accounts for 25% of a market and 20% of its daily volume, it can exert a powerful influence over pricing, something not realisable in traditional polling. While defenders of efficient markets could argue that any difference between market-implied probabilities and unbiased guesses should be arbitraged away by rational actors, we should be reminded how this is far from being straightforward given the current structures of those platforms—including transaction costs. In addition, any arbitrageur would run the risk of an adverse market resolution even in case of a victory of the opponent candidate, a risk exacerbated by the current dispute resolution structure of some of those platforms.

The Wash Trading Issues

As analysed by Omer and reported on Fortune, the phenomenon of wash trading on Polymarket is another troubling indicator of manipulation on the platform. Wash trading has been found to constitute a huge portion of Polymarket’s reported activity most recently. Chaos Labs used on-chain data to identify patterns indicative of wash trading, isolating high-frequency transactions by users who appeared to be engaged in artificial volume inflation. While inflated volumes are definitely not new on crypto platforms, at least those debating token launches in order to farm tokens/ points/ shards/ pills, the practice might be particularly dangerous on platforms that are positioning themselves to be reliable sources of truth—on which others can rely for judgment or additional applications.

How does Polymarket count volume? While volume is often used as a proxy for genuine interest and activity, it can sometimes be misleading—a vanity metric rather than a true reflection of user engagement. Polymarket, by design, publishes all trade execution data on Polygon, and this enables researchers, users, and builders alike to audit and analyse Polymarket data. As Omer dug into the data, he noticed that the notional volume figures didn’t entirely align with what we observed on-chain. By calculating share value traded alongside their USD equivalents from Polymarket’s OrderMatched events, he found that while share volume almost exactly matched the reported USD volume—slight difference due to update frequency, the $ volume was around 64% lower than the figures on-screen. You can read more about this directly on Omer’s X thread. The attack surface allowing volume manipulators to inflate reported volumes by wash-trading ≤ 1c shares seems to have been exploited in practice, with 29% of reported volumes coming from transactions in which the taker traded the cheapest possible shares. While some portion of this 29% reflects genuine bets on long-shot candidates, a significant amount clearly does not. This issue is even more pronounced when we zoom out to Polymarket’s volume in aggregate: across all markets, c. 41% of Polymarket’s reported volume to date has come from transactions at an avg price of ≤ 1c, i.e. in which USD volume has been overstated by between 10,000-100,000%.

We see two possible drivers explaining this behaviour:

Users may be targeting low-probability markets as a low-risk, capital-efficient way to qualify for (i.e. farm) a future airdrop

Seemingly irrational traders took positions as a deliberate attempt to inflate reported volume by exploiting Polymarket's unique volume measurement

While I don’t intend to draw definitive conclusions, it’s worth acknowledging that farming is far from a novel phenomenon in crypto markets. This issue, however, gains particular significance when the public begins to interpret these markets as faithful representations of popular will.

So, does Polymarket have what it takes to be considered a well-formed market?

Diverse risk aversion → uncertain. The distribution of risk tolerance among Polymarket participants remains an open question. Betting markets (especially crypto-enabled ones) often skew towards high-risk tolerance, which may not reflect the broader population’s preferences. This distinction matters, particularly in political predictions where participants could influence outcomes they’re wagering on, unlike sports betting. The question of whether Polymarket participants accurately mirror the electorate’s risk profile, then, remains unresolved

Liquidity and market depth → negative. It is clear that Polymarket’s structure doesn’t yet display the liquidity and market depth needed for its prices to serve as reliable indicators of probability. Without a sufficiently deep market, we can’t take prices at face value as unbiased reflections of underlying events

Wealth distribution → negative. Events like those of August 17th underscore how concentrated wealth in these markets impacts price formation. Even absent overt manipulation, a wealthy better can shift perceived preferences in a way traditional polls cannot

This isn’t a verdict against Polymarket per se. It’s still early days for these platforms, and I personally am observing with undeniable excitement the emergence of such mechanisms within decentralised finance. Polymarket and its peers, however, are still far from being reliable predictors of complex social dynamics.

Yet, Reactions Are Fast When Stakes Are High

While on-chain data provide the ability for anyone with patience and skill to dig deep, few seem willing to do the work. Despite data suggesting otherwise, Polymarket and Kalshi continue to be cited by mainstream media as credible, unbiased predictors of the upcoming election. Naturally, the leading side is eager to amplify this narrative even further.

Critics argue that, historically, big money has always shaped information and perceptions through carefully crafted lenses. Today, however, prediction markets seem to present a strikingly cost-effective way to sway public opinion on a global scale. Since July 2024, Google Trends shows a 10x increase in searches for prediction markets, with interest continuing to print record highs this month, reflecting a surge in attention as election day nears.

On election markets efficiency → Market efficiency is a common thing solely in university classrooms, and it takes a while (and a ton of liquidity) to make a market truly efficient. Efficient market theory argues that prices in a market should reflect all available information, creating a spectrum from weak to strong forms of efficiency. In weak-form efficiency prices incorporate all past public information, while in strong-form efficiency prices capture all public and private insights.

Prediction markets can strive to operate at best within a weak form of efficiency, while equity markets typically are considered semi-strong efficient. The reason is structural: given the impact on social consensus and voting behaviour of predictions—and polls, in election markets prices express some form of self-reflexivity that can incentivise market manipulators. The situation would be different for prediction markets focused on sport or meteorological events. Prediction markets, in other words, could enable speculative traders to leverage structural market reflexivity by betting heavily on events where price divergence from reality can be easily influenced. In more mathematical terminology, buying events where prices are significantly richer than unbiased probabilities might be a dominant strategy even for the most informed trader, assuming they are large enough to influence prices further. This seems consistent with what has currently been observed.

The Oracle Problem

Fair probability pricing is just one component of a prediction market’s architecture. At their core, prediction markets are event resolution markets: platforms where opposing sides wager on the binary outcome of a defined event. This framing underscores that beyond order matching and a user-friendly front end, dispute resolution mechanisms are critical to the integrity of the market structure. As previously explored in DR #63, early platforms like Augur tried to navigate the complexities of decentralised resolutions, while Polymarket relies on UMA’s model for dispute resolution—a choice that reflects how foundational these mechanisms are to shaping credible, reliable markets.

UMA dynamics → The UMA dispute resolution process offers fertile grounds for game-theoretical nerds. In essence, when a dispute arises, any participant can initiate a request to UMA’s Data Verification Mechanism—DVM, which then alerts $UMA token holders to the ongoing issue. The requests triggers a voting period, during which off-chain discussion can unfold, allowing stakeholders to present evidence, opinions, arguments, for or against specific outcomes. At the conclusion of the voting window token holders cast their votes on-chain, proportionally to the amount of $UMA tokens staked—in some sort of proof-of-stake system where those with greater financial commitment have more influence over the resolution. Participants aligning with the majority consensus are rewarded, while those dissenting face financial penalties. Whether this system incentivises honest participation depends on many assumptions circa the distribution of $UMA tokens.

The UMA oracle model is more complex, with numerous nuances and parameters. However, the core principle is clear: holding a majority of $UMA tokens grants decisive influence over dispute resolutions. This majority control enables the holder to effectively determine the outcomes of the disputes leveraging the system.

A Probabilistic Analysis of Polymarket-UMA Dynamics

Polymarket’s open interest is currently c. $300m, compared to $UMA’s market cap of c. $220m. With an investment of c. $110m (half of $UMA’s float) someone could theoretically amass enough tokens to influence the oracle’s dispute resolutions, thereby affecting outcomes on platforms like Polymarket that rely on the protocol.

The scenario, however, is more complex in practice. On the one hand, accumulating a significant amount of $UMA would likely impact price due to thin market conditions, increasing the cost of acquisition. On the other, any perceived ongoing manipulation of the UMA mechanism could undermine confidence on the oracle system, potentially devaluing the token and diminishing the attacker’s investment. There’s not enough data to do good game theory and I’d stick to the $110m estimate for oracle control.

Introducing the CVM → The Corruption Value Multiple (CVM) is a metric that compares the cost of manipulating a market to the potential gains from such manipulation. In this context, with Polymarket’s open interest at c. $300m and UMA’s market capitalisation around c. $220m, the CVM would be ($300 / 2) / $110 = 1.36x, indicating that for every $1 invested in manipulation there’s a potential gain of $1.36. The 1.36x number might well understate CVM since it assumes that (a) every $UMA always participate in voting—while that number seems to be actually c. 20%, and (b) resolutions are trivial—in reality ambiguous wording, delays in result verification, and the potential for social manipulation make things more complicated.

My gut feeling says that the $$$ required to control the oracle are much, much less. Or, said in other words, that the rationally justifiable overestimation of an event vs. its true probability is much much higher. In the example below we make the case with a few assumptions, demonstrating how a rational trader with the ability to manipulate the market would rationally bid significantly higher than true probabilities knowing of the event resolution mechanism. This simplified math obviously ignores reflexivity and more complex game theory, but makes my point.

Final Remarks

This post is not intended to criticise Polymarket or any other emerging crypto-based prediction market. As an author, researcher, and builder, I remain fascinated by those platforms and my goal is to protect them from opportunistic speculators. The pre-election hype surrounding Polymarket may boost its fundraising efforts (if I were developing a prediction market I’d consider raising funds every four years) but it also risks overwhelming the project’s design and financial capacity with excessive volumes.

In a world driven by hyper-intelligence and aggressive capitalism, patience might be the most challenging yet most valuable virtue.

what do you think of vitalik's last memo? https://vitalik.eth.limo/general/2024/11/09/infofinance.html you seem to be making a very strong case against what he calls info finance, by showing how easy a prediction market can be corrupted by a sufficiently wealthy / determined actor...