# 10 | Crypto-Alt-Lending: a Primer

I Reviewed an On-Chain Structured Finance Deal - I Know, It Doesn't Sound Funny

This is another issue of Dirt Roads. Those are not recaps of the most recent news, nor investment advice, just deep reflections on the important stuff happening at the back end of banking. The time we are sharing through DR is precious to me, I won’t make abuse of it.

Expanding the Lending Club

Disclaimer. Although the key ideas behind this week’s post are grounded on my direct experience as private investor, no non-public, competition-sensitive, or legally-protected information has been shared, at least voluntarily.

I must admit I have a weak spot for some legendary structured credit investors. The contractual and financial tools at disposal to extract (risk-adjusted) returns are vast, and the variables impacting valuations even vaster. In addition, credit has sufficiently reliable contractual cash flows to do some sensitive quantitative analysis. To me, structured credit investing feels a bit like basketball or tennis: the best player typically wins. Down the capital structure things change, and successful equity stories get more romantic, potentially transformational, but also more erratic and path-dependant. Equity investing tastes a bit like football.

Lone Star’s founder and Pontifex Maximus, John Grayken, is, to me, the quintessential credit investor. Founded in 1995, over the years Lone Star remained loyal to the asset class that made the firm famous, distressed lending - mainly backed by real estate, and to a process of i) discounted acquisitions, ii) workouts, iii) sophisticated structuring, iv) competitive sales, that learned to master like nobody else. From a 2016 bio piece on Grayken by Nathan Vardi from Forbes:

And if you thought banks behaving badly in America were a thing of the past, Grayken's Texas mortgage company, Caliber Home Loans, has become infamous for its tactics as a servicer of subprime loans, some dating back to before the financial crisis. Caliber is one of the largest and fastest-growing mortgage companies in the nation, managing more than 325,000 mortgages and worth some $70 billion. A good number of Caliber's mortgages were purchased by Lone Star Funds at a deep discount--70 cents on the dollar--during auctions held by wards of the state Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the Department of Housing & Urban Development.

In a stroke of brilliant financial maneuvering Lone Star bundled some of the mortgages into bonds and sold them to investors, immediately booking large profits. At the same time Caliber offered "temporary" loan modifications to distressed borrowers that consisted of five-year interest-only payment plans but failed to offer the homeowners any permanent relief through principal reduction. At the end of the five years these loans would revert back to the original payment terms, with all the deferred payments added in.

Lone Star is not alone in this game. Cerberus, Apollo, Blackstone, and others are in it as well, but I learned a lot reviewing the securitisation docs of RMBSs pools that Lone Star was buying from the state agencies and flipping to senior notes investors. I am not a credit trader, but I have advised and invested in credit institutions all my life, so the lessons felt relevant. This is what I learned:

The most important indicator of success is always acquisition price

You will get paid extraordinary returns to sustain risk that is higher although not much higher than the standard - but that is often optically unpleasant or with reputational strings attached

You can optimise the returns of what you keep by structuring appropriately and marketing what you don’t want to the right investors

Credit underwriting is the art of drafting the right documentation rather than applying the latest state-of-the-art predictive tech

If you don’t know the borrower, you must know well the guarantor(s)

Credit investment will make you boring at the eyes of others, but do not care

When the world of alternative, structured, lending collided with that of traditional banking, I tried to apply those same lessons. It was a test-and-learn process. I hope the same lessons will assist me now that lending, or credit investment in general, is starting its long migration to the blockchain.

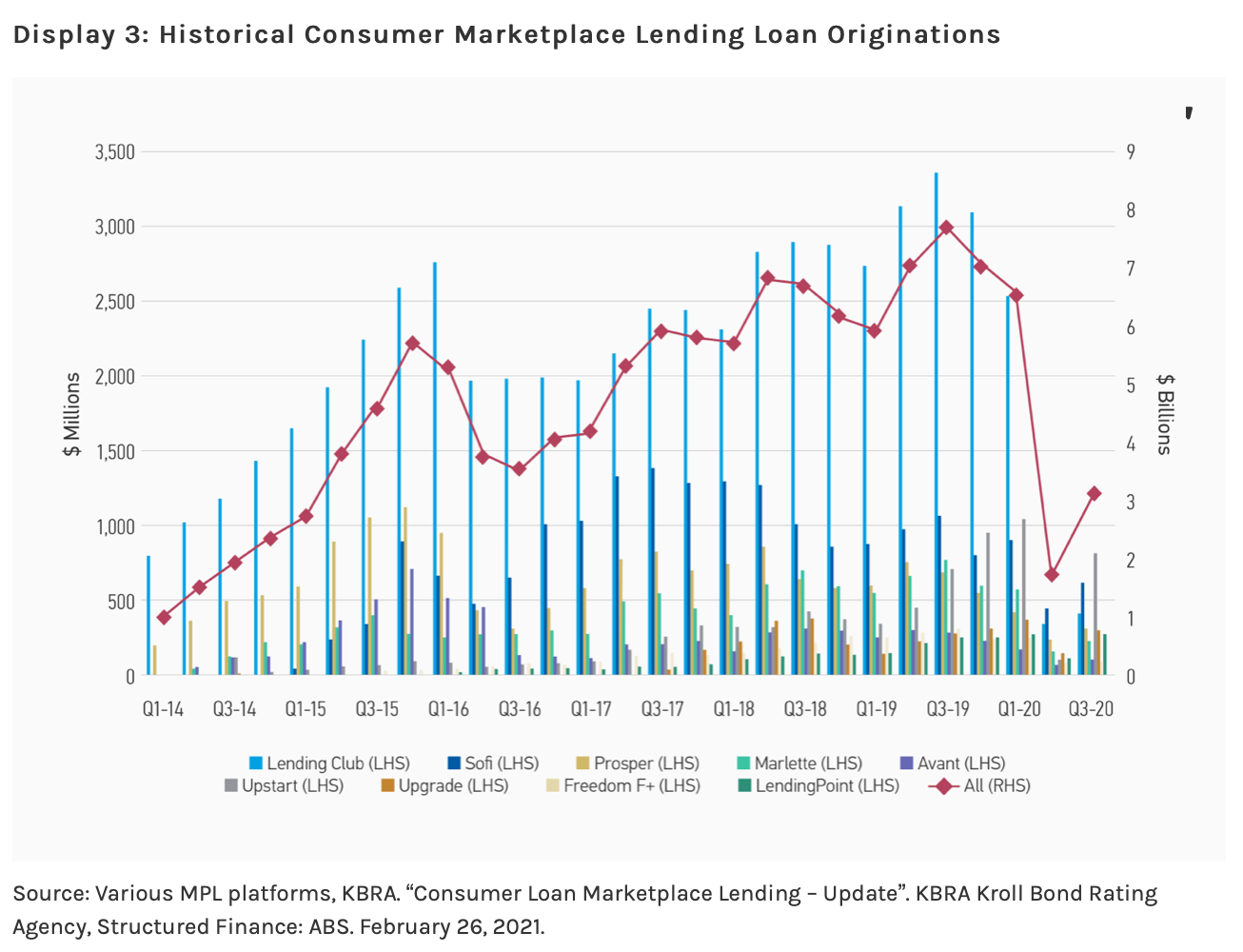

Banks’ Wonderings In Alt-Lending

Zopa, founded in 2005 in the UK, was probably the first tech-enabled company to bring peer-to-peer (P2P) lending into mainstream. It offered the ability to match retail investors and borrowers via a web platform and an algorithmic risk engine, promising to unlock credit for all while providing juicy returns for capital providers. A few iterations of the P2P lending model followed through, hundreds of new players entered the sector, and most first movers evolved into highly sophisticated financial institutions - sometimes owning full-fledge banking licenses.

Although most people still call them P2P or marketplace lenders, I believe the most appropriate definition for tech-enabled, non-bank, credit originators would be alt-lenders. The P2P model showed scalability issues since its very beginnings; for as inclusive as it sounds, retail capital has been historically quite an inefficient source of financing (too granular, nervous, unpredictable, regulated, unsophisticated, etc.) and today most alt-lenders rely on institutional funding. In addition, most of those originators do not run a marketplace model that matches sources and uses of funds, but actually negotiate long-term relationships with few liquidity providers under very specific terms to feed their business while they are focused on growth.

When, a few years back, I approached the alt-lending space as a private equity professional, I was intrigued to realise that the biggest credit investors worldwide (i.e. the banks!) were basically absent from it. Banks were still going the internalised way, while alt-lenders relied mostly on VCs, credit hedge funds, and family offices as sources of liquidity. With hurdle returns at > 20%, 10-20%, and 5-10% respectively, it was puzzling for me to understand why banks, for which most of the lending book yielded < 5%, weren't interested. We had a wall of money characterised by negligible cost of funding crowding traditional low-yield lending products like mortgages, and on the other side a plethora of new lending needs ready to pay the double-digit costs demanded by higher-risk investors. Risk appetite was part of the story, as was regulation, but to me it still made little sense banks weren’t dedicating significant time to study the sector.

A business case followed. Even when ignoring the potential benefits of partnering for a traditional bank (geographical and sectorial diversification, better client targeting with innovative products, lower marketing costs, higher operating leverage), overwriting expected credit losses by a factor of 2-4x, and adopting extreme regulatory prudence (i.e. in risk-weighting and capital buffering), estimated equity returns remained in the 15-25% range.

So we decided to give it a try.

The result was, in hindsight, unsurprising: superior financial returns existed, but required an incredible amount of work. As it typically happens for credit investments, the devil was in the detail. Finding early gems (those with a product well targeted to a specific niche, an attractive client acquisition mechanism, and a solid alignment of risks and rewards) that were still open to negotiate stringent terms was a job made of landscape scraping, tens of meetings, deep analytics, and intense collaboration with the management. There was an easier middle way, i.e. accessing the credit flows originated by well established and sizeable alt-players like Funding Circle or Younited Credit, but that had way less attractive returns. After all, there is no free lunch in the credit market. Unless you are Greensill of course.

Understanding the Value Flow

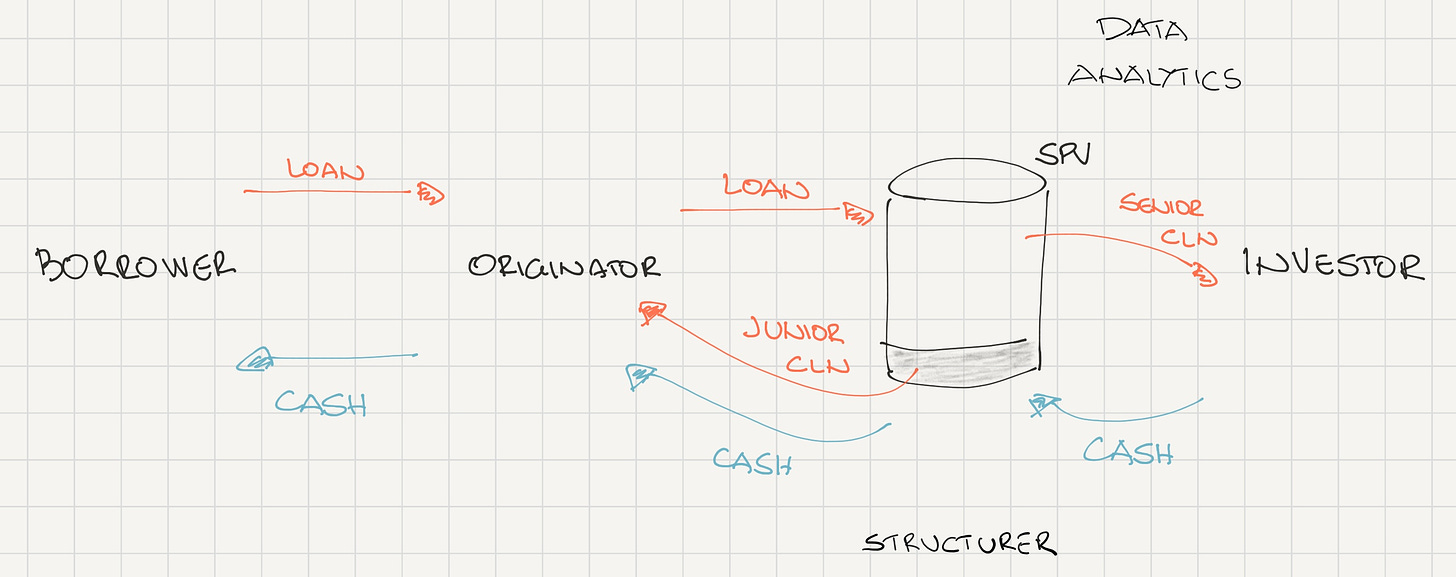

There are several ways a bank (or more generally an institutional investor) can access the flow of credit assets generated by alt-lenders, but the typical process goes as follows:

A Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) is set up, often with the help of a structurer, ready to purchase a certain predetermined amount of credit assets, issued under specific underwriting criteria agreed between a credit originator and the SPV investors

A borrower approaches the originator with a financing need, typically through its acquisition channels

The originator performs credit quality (and KYC) checks, in accordance with the underwriting criteria agreed with the SPV investor, structures and prices loans, and issues them

The issued loans get (quasi simultaneously) acquired by the SPV, in exchange for cash - the cash ultimately (minus specific origination fees and other costs) gets distributed to the borrowers

In order to finance the loans acquisition, the SPV issues credit-linked notes (CLNs) to its investors, who contribute the required cash

The originator services the loans, by collecting instalments and being the first line of defence for any required credit collection activity

The cash collected flows back to the SPV that distributes it to the investors based on a pre-approved distribution schedule and seniority

Even in such a stylised process, there are several very important nuances to be highlighted:

Investors sign an agreement to finance the forward flow of originated loans - i.e. credit assets that do not exist yet; this makes it different from a securitisation of assets already issued - and rated, and gives certainty to the originators that the money will be there when the borrowers come for business

Investors have full visibility and control of the underwriting criteria, models, and originated credit tapes and can stop the flow of new loans in case the credit assets do not comply1

For a proper alignment of interests, the investors require the originator to be also an investor in the SPV, typically junior to the others - i.e. suffering the first loss up to 5-10% of the total value of the SPV but getting an implied return that is higher than that of senior investors

There is often an excess spread built into the cash coming in the SPV from the servicing of the loans (minus fees) and what has been agreed to be paid out of the SPV; this allows the junior tranche to be replenished in case of erosion, enhancing credit quality

The SPV has typically a reinvestment period and runoff period, meaning that the proceeds from the repayments can be reinvested into new loans within a specific timeframe

It is rare for the CLNs to be liquid, meaning that investors are expected to hold them until the maturity of the underlying loans occurs

Investors have a series of additional liens of defence that try to align interests further, e.g. pledge on the originator’s assets, buyback guarantees, credit insurance, etc.

A Successful Partnership

Partnerships like the one described above can be highly beneficial for both parties. On the one hand, serious capital from institutional providers can be transformational for start-ups that are yet to turn profitable and survive on (very expensive) venture funding. On the other, start-up originators have proven to be faster in innovating, more attentive to emerging needs, and better at extracting high implied interest rates - through more sophisticated pricing and shorter durations.

There is one additional element that is often overlooked. For as much as banks remain the emblematic dinosaurs of TradFi, it turns out they are (on average) really good at pricing credit when compared to the smart guys coming from hedge funds and start-ups. There is an innate conservatism coming from years of risk committee politics, and an aversion to the explosive hockey stick growth preached in start-up land. This too, is quite useful when you need to scale up a new asset class.

Ultimately, banks have a lot of patience and the luxury of levering up their assets at zero or negative costs in a a way no other credit investor can, and this dramatically reduces their cost of capital - hopefully also improving the borrowing experience on the other side. It is difficult to understand why we are still at the infancy of bank-backed alt-lending.

Does Alt-Lending Need DeFi Then?

For as much as banks are difficult animals to deal with, my short answer is probably not today. Traditional money of any kind is abundant, very cheap, and accessing DeFi protocols to finance real world assets doesn’t create any shortcut, but rather adds another layer of complexity to the value flow described above.

At the same time we live in the enthusiastic early years of blockchain technology, and teams are building bridges simply because it can be done, it is elegant, and it might turn relevant when the excessive liquidity in the system dries up, and especially when the rest of the ecosystem aligns along the decentralised vision of some of the DeFi funders. There is a tendency of tokenising everything that might actually turn very useful at some point.

I have touched on the recent collaboration between Centrifuge and MakerDAO already. In this post, we will go deeper in analysing how the structuring of New Silver (NS), as the first real world collateral on the protocol, has been approached and see if the Grayken Rules have been followed.

NS-DROP: Collateral Onboarding

You can find a detailed description of New Silver the originator, the structuring, and the key process items by navigating MakerDAO’s forums and we won’t repeat them here. Instead, we will use a description by exception approach, highlighting what a credit investor would point out.

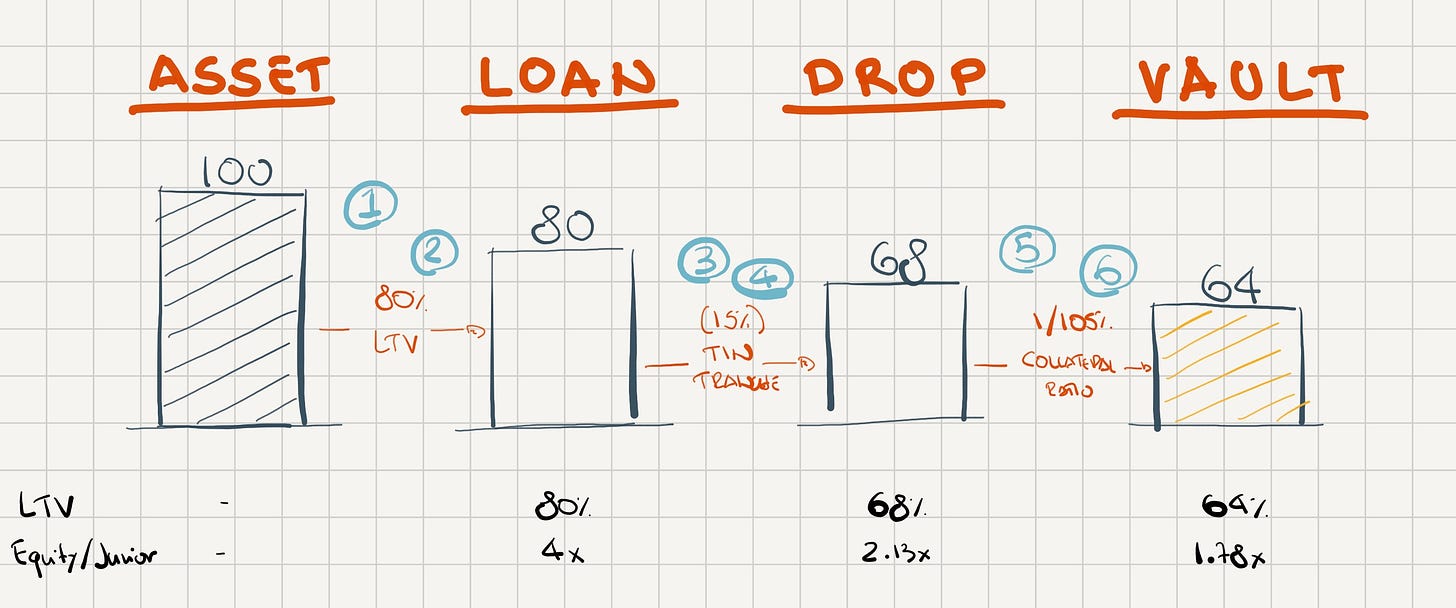

Understanding starting leverage. DeFi value flow differs slight vs. its TradFi counterpart. In TradFi, a bank would lever the investment with deposits, way more deposits than equity capital - proportional to the bank’s capital ratio, Maker’s vault is instead under-collateralised, because it doesn’t benefit from any diversification across assets or central banking back-up, and this has a negative impact on them. Where the ultimate borrower pays 10-12%, Maker vault has a stability fee of 3.5% - but with much less leverage. This is fair, but the flowchart highlights few open points - I numbered them:

Can we trust the independent appraisal of the loan?

What is the seniority of the loan vs. others such as construction loan?

Who will be the TIN investors? Is the originator required to invest in TIN?

With an illiquid market and few buyers, how are TIN vs. DROP tranches priced?

Who’s plugging the DROP portion not financeable with DAI? Co-investors?

Is there excess spread between what flows into the SPV and the stability fee?

Credit investing is painful, but the devil is in the detail. For as much as mortgage loans can be incredibly low margin for banks, their regulatory treatment allows banks to lever their RoE up to 10x. The risk-adjusted returns for equity holders are incredibly attractive. How could an under-collateralised DeFi lender compete? Asking the right questions means trying to answer this one.

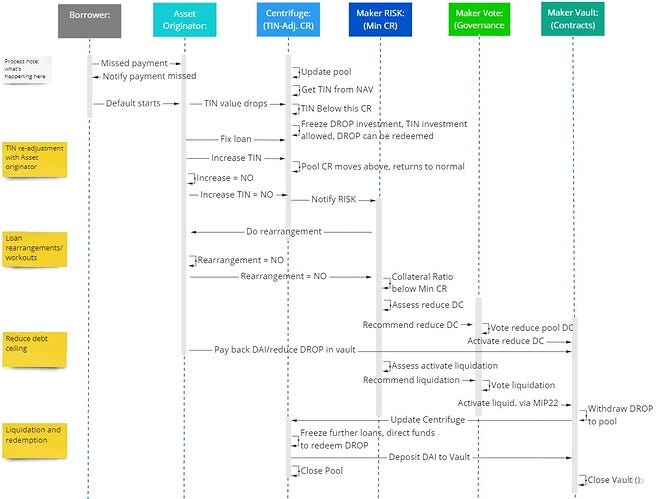

Following the evolution of a loan pool. The loans’ Net Asset Value (NAV) moves with time, based on the originator’s valuation and a smart contract managed by Centrifuge and monitored by MakerDAO. If the TIN value falls below the minimum collateralization ratio set for the originator, a liquidation is triggered. Differently from more traditional collaterals, there are no keepers or automatic facilitators involved in the liquidation – which is actually closer to a mitigating action: simplistically, Centrifuge freezes incoming funds to redeem DROP tokens until the collateralisation ratio is re-established, and also stops further loans. A detailed workflow has been posted in Maker’s forums - below.

Several points remain open here as well:

A lot depends on the originator’s valuation model, and whether the firms have the required skills and incentives to provide an appropriate periodic appraisal remains to be seen. With no observed default in New Silver’s history (USD 30m originated) and considering the lumpy size and nature of the underlying loan pool, history cannot be a good proxy for the future, and real credit deterioration may manifest itself in one big flush. There might be other asset classes (e.g. invoice financing, e-commerce revenue-based financing, car loans, unsecured personal loans) that would be better suited for a statistical valuation approach

An increase in NAV, it seems from the docs, can increase the DAI minted proportionally - this has the implied effect of recycling the proceeds; we should investigate how accrued returns vs. cash returns are treated in the valuation, both liquidity and accounting-wise

Maker continuously oversees the evolution of the credit quality, but are we sure the DAO has the right skills, and incentives, to do that? In banking institutions risk and business departments create competition between risk aversion and risk taking, how’s this balance recreated in Maker’s protocol?

Concluding Remarks

Dirt Roads does not intend to provide a complete audit of structured credit, and of on-chain structured credit in particular. The aim of this post was to highlight some of the complexities involved in the underwriting, structuring, and onboarding of alt-loans. Given the need of DeFi to diversify across collateral pools, to develop specific skills to assess each credit class, and considering the competition existing in providing liquidity to alt-credit, getting compensated for the effort will be hard. Maker has the ambition to onboard USD 300m of real world assets by 2022, i.e. 10-30 originators; the relative effort vs. that required to onboard a single crypto-token is huge.

It is true, some use cases, digitally native, are already prone to find digital financing. Paperchain’s synthetic financing backed by media content is an example. However, as we discussed in prior posts, some of the financing needs of value originators might be only temporary. We have companies like Superfluid (already discussed on DR) aiming at real-time programmability of value streams, and juggernauts like FTX with the ambition of becoming the everything exchange - the Generalist trilogy on FTX is a masterpiece. Value could be digested by DeFi without the need for off-chain/ on-chain bridges. Until then, conservatism and strict alignment of incentives remain the only mitigating factors available.

Maker’s vision of universal on-chain securitisation of value (to back a growing demand for DAI) might be hard to come until many new types of collateral enter the blockchain. Gaming, media content, and data monetisation are my personal picks, but we might all remain surprised by something completely new emerging. Until that time I fear that decentralised lending will remain a niche support service to crypto trading.

While researching for this post of DR I had the pleasure of conversing with Martin Quensel, Centrifuge’s co-founder and COO. Providing support services to on-chain securitisation might be only the intermediate step for a firm that is instead aiming at creating an infrastructural, fully decentralised, meta-layer to be the backbone of on-chain structured lending. In Martin’s vision, several protocols might plug in and out Centrifuge’s main infrastructure to manage the lending building blocks that are currently curated by humans. Centrifuge will offer the mainframe for this type of truly decentralised credit, governed by the CFG token holders - already existing and at c. USD 500m market cap. Martin’s future is one of sound algorithmic checks and balances, permission-less pooled guarantees (e.g. for supply chain financing), parameterisable smart contracts, and frictionless value flowing between providers and users of capital. We will have the opportunity to discuss this further in DR, since it sits at the core of the DeFi that matters, i.e. that focused on facilitating the universal access to credit and on eliminating the costs arising from lack of trust and inefficiencies. I am sure that by that time the Grayken Rules will remain precious for programmers as much as they are today for investors and credit offices.

Innovating is a process. It starts with sourcing ideas, and proceeds with disseminating those ideas for testing, funding and high-quality execution. For this reason, it is collegial in nature. If you have great ideas you want to explore together, great companies that should be on Dirt Roads radar, or topics you would like to co-author on DR, please feel free to reply to this email or contact me on Twitter.

This is even more important, for regulatory reasons, if the investor is a bank and wants those credit assets to be treated as look-through loans originated by the bank itself; this would guarantee the bank an ability to leverage those loans, obtaining a return on equity that is 3-4x higher than the net credit yield

“Traditional money of any kind is abundant, very cheap, and accessing DeFi protocols to finance real world assets doesn’t create any shortcut, but rather adds another layer of complexity to the value flow described above.”

Spot on. In the long run, the situation might of course flip around and securitising off chain will be the more complex process. Either way, in the end what matters for the product are the originator’s underwriting capabilities — DeFi is just a source of capital and doesn’t change that. If it gets cheap and abundant enough it may become a meaningful alternative to traditional sources, but as you point out it takes expertise to finance those deals. Tokenising in principle makes the product accessible to a wider investor base, but as seen with P2P lending that’s not necessarily an advantage.